by Richard D. L. Fulton

Lehman & the U.S.S. Barb

The Sub That “Sunk” a Train

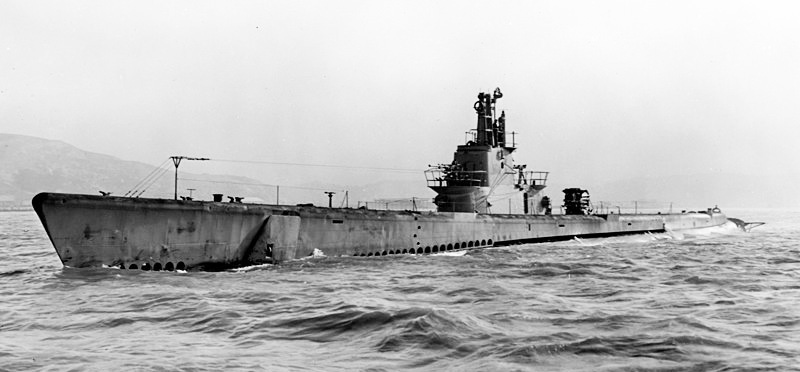

The World War II submarine U.S.S. Barb (also known by its naval designation SS-220), was said to have compiled “one of the most outstanding records of any U.S. submarine in the war,” sinking more than 96,600 tons of Japanese ships—a total of 17 Japanese ships, including an aircraft carrier.

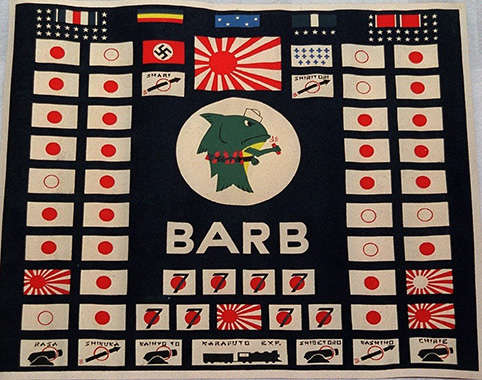

Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Eugene “Lucky” Fluckey, the Barb’s commander earned the Navy Cross and Medal of Honor, and the ship and its crew were awarded four Presidential Unit Citations and a Navy Unit Commendation with eight battle stars.

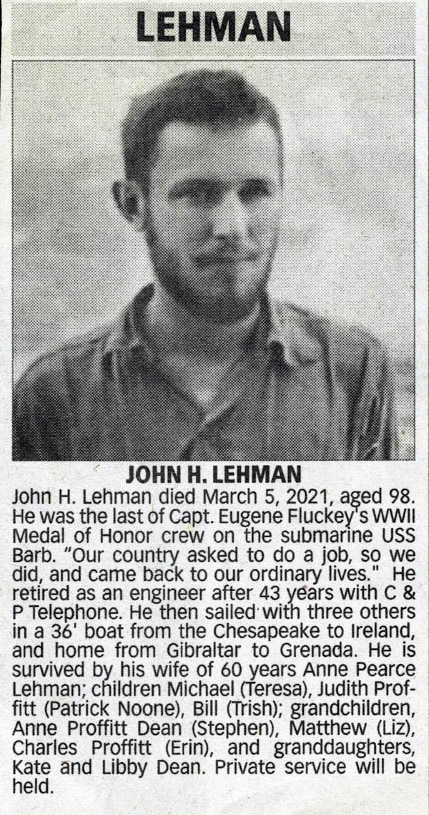

The late John Lehman, born in Reed (near Hagerstown), ultimately became a resident of Frederick.

Lehman joined the Navy in the wake of the Korean War as a trained radio operator, having attended the Bliss Electrical School in Tacoma Park. He joined the Navy before he could be drafted into the Army, wherein he received additional training, notably in the field of radar.

He was subsequently sent to London, Connecticut, to attend classes on submarine-specific radar.

Following the completion of his education in Connecticut, he returned to Mare Island, California, where he was assigned to the crew of the U.S.S. Barb.

Initially, the Barb was dispatched to the North Atlantic under Captain John Waterman, where the submarine sank only a single German ship. The Barb was then assigned to Pearl Harbor, where Fluckey assumed command.

With Lehman manning the radar, the Barb sank four Japanese ships, including an aircraft carrier in the East China Sea, off the coast of China, before making its way up to a Japanese-occupied port on the China coast, where the crew of the Barb took on a Japanese sitting duck convoy of 30 anchored ships. About that raid, Lehman stated, “(sneaking into the harbor) was the easy part… Getting out of the harbor safely into open water was the tricky part,” adding that upon escape, the submarine was forced to remain on the surface in order to safely negotiate mines and rocks.

For this daring assault alone, Fluckey was awarded the Medal of Honor, and the crew of the Barb received the Presidential Unit Citation.

The Barb also participated in a rescue operation when an unmarked Japanese ship—designated the “Hell ship”—transporting Australian and British prisoners of war was tragically sunk. The crew of the submarine rescued 14 of the POWs.

But one of the Barb’s more notorious ventures began on July 19, 1945, when the ship sailed close to the Japanese shoreline, and the crew noted a railroad that had been constructed with the apparent intent that it be used for transporting military supplies. The submarine sat idle for several days to allow the crew to observe the arrival and departure of the supply trains.

Then on July 23, the submarine closed in on the shoreline, followed by eight of the ship’s crew, launching themselves in a small boat to gain access to the beach. According to warhistory.com, the team then crawled through high grass, across a highway and a ditch, and then began to lay pressure-sensitive explosives along the train tracks. Lehman said he tried to volunteer for the mission, but the commander was not about to send his primary radar operator into the attack.

In a little over an hour, after the assault team was back on board the sub, a supply train triggered the explosives and blew up, and the rest is history. The attack became the only ground combat assault carried out upon Japanese soil in the war, and the Barb became the only submarine with the image of a train sewn onto their battle flag.

Fluckey described Lehman as one of the best radar men with whom he had ever sailed, citing Lehman several times in the lieutenant commander’s book, Thunder Below.

Lehman passed away in Frederick in 2021, the last surviving crew member of the Barb under Fluckey’s command.

As to the fate of the U.S.S. Barb, it was decommissioned and loaned to the Italian Navy, who renamed it the Enrico Tazzoli. Still in Italian hands, the ship was sold in 1972 for scrap for $100,000, according to warhistory.com.