by Richard D. L. Fulton

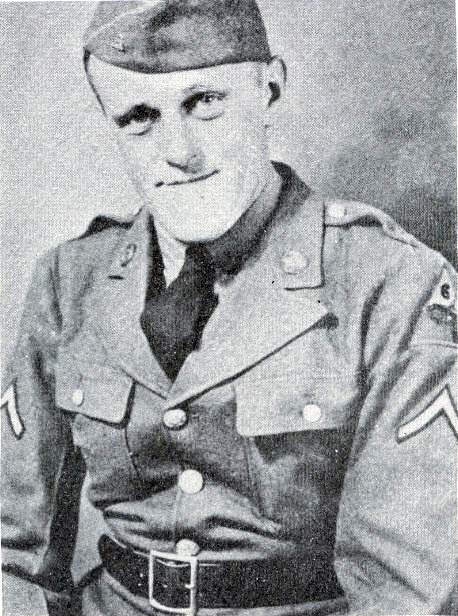

Staff Sgt. Richard J. Tieman

Richard J. Tieman was born on November 21, 1981, at the Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco, and subsequently resided in Waynesboro, the residence of his father, Richard Tieman, Jr., and his stepmother, Diane Tieman.

Tieman also had one brother, Tyler. Tyler Tieman described his brother, in an article published on May 21, 2010, by The (Harrisburg) Patriot News, as having been “full of life and fun to be around, easy-going and loved his country,” additionally noting that his brother was also a Philadelphia Eagles fan.

Tieman’s father further stated in the newspaper that, “He liked playing sports, fishing, lifting weights, and occasional drinking. The things that other young people typically do.”

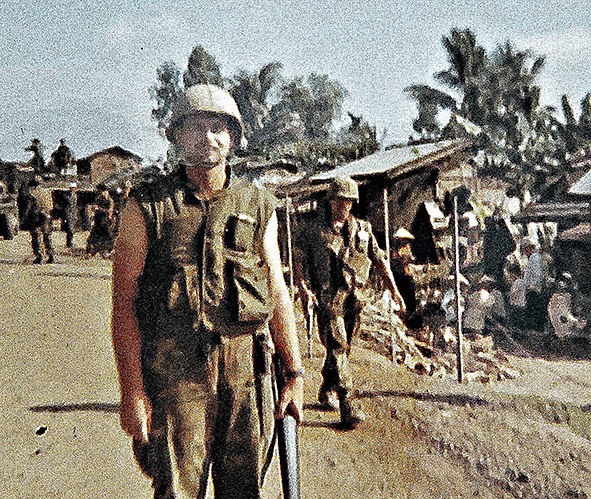

Tieman enlisted in the Army at age 18 on September 29, 1999, and his first assignment had been to serve in the Support Battalion in the 3rd Corps at Fort Hood, Texas. This was followed by his deployment for two tours of duty in the 54th Combat Engineer Battalion in Bamberg, Germany, from 2002 to 2007, during which he was promoted to sergeant and awarded the Combat Action Badge, according to his father (via goldstarfamilyregistry.com).

Tieman was serving his third tour of duty with the STB (Special Troops Battalion), V Corps, based in Heidelberg, Germany, when he and his unit were deployed to Iraq in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, when he was killed, according to the Public Opinion.

The York Dispatch reported on May 20, 2010, that Tieman died, along with four other soldiers, and other individuals (a Canadian colonel and a dozen Afghans), when a NATO convoy, in which they were riding, was attacked in Kabul, Afghanistan. Tieman’s father told the Public Opinion that the attack was executed by a suicide car bomber armed with 1,700 pounds of explosives.

Bob Harris, director of the Franklin County Veterans Affairs Office, reportedly had told the Public Opinion that Tieman “was in charge of the convoy as it was passing the embassy when the suicide bomber set off the bomb.”

Tieman was killed a month after having married his wife, Staff Sergeant Paulina (also in the Army), in April, and was only two months away from coming home for additional military training and to see his wife, according to the May 20 and May 29, 2010, editions of the Public Opinion.

When Tieman was killed, his wife had learned of his death while still being stationed at Fort Riley in Kansas. His father reportedly told the Public Opinion in an earlier story that the newlyweds had been considering honeymooning in Australia.

Staff Sgt. Tieman’s body was returned back home via the Dover Air Force Base.

The Public Opinion reported in the May 23, 2010, edition that some 30 individuals held a memorial service in the parking lot of the Waynesboro K-Mart on May 22, noting that, “Community officials, police, fire, and ambulance personnel surrounded the family of the soldier… The speeches were short. The event lasted 15 minutes.”

In addition, American flags were placed throughout the downtown area.

As a further tribute, the Letterkenny Child Development Center was named in honor of Tieman in a dedication ceremony held on June 8. Tieman’s widow, Paulina, told the Public Opinion that naming the center in honor of her deceased husband was appropriate. “Kids adored him,” she said, adding, “It could be his smile. He was just a funny guy.”

Tieman’s body was laid to rest on June 11, 2010, in the Arlington National Cemetery. The Public Opinion reported that Courtney Wittmann, public affairs officer for the Arlington National Cemetery, stated that the national cemetery had provided the pallbearers, firing party, and the bugler for the burial ceremony.

Staff Sgt. Tieman was awarded the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart.

Waynesboro Mayor Richard Starliper reportedly had told the Public Opinion that Tieman was the first Waynesboro resident to have been killed in action since the Vietnam War.

Staff Sgt. Richard J. Tieman