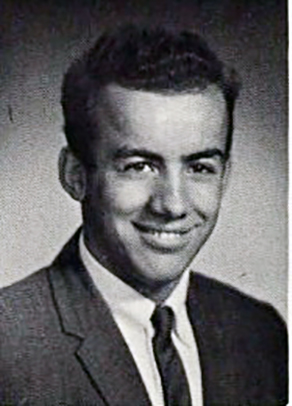

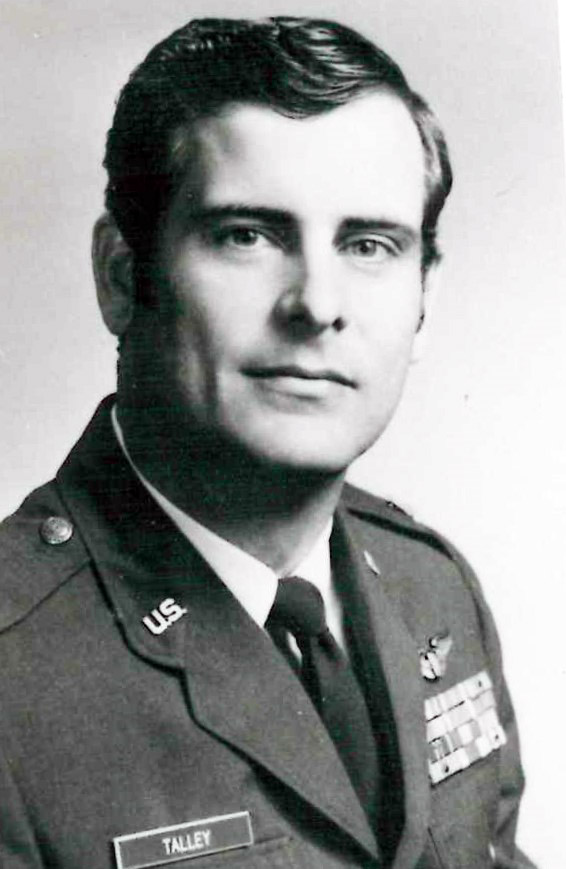

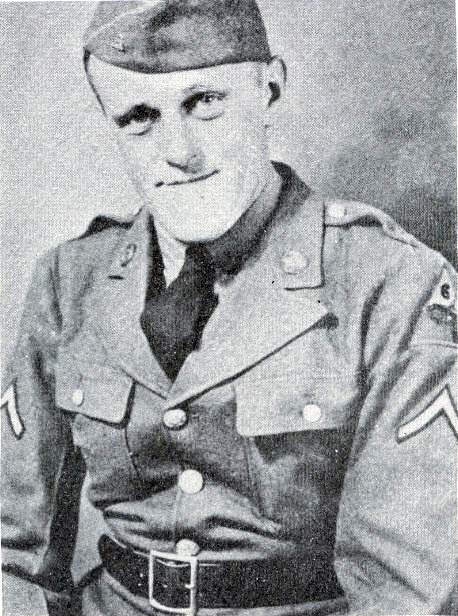

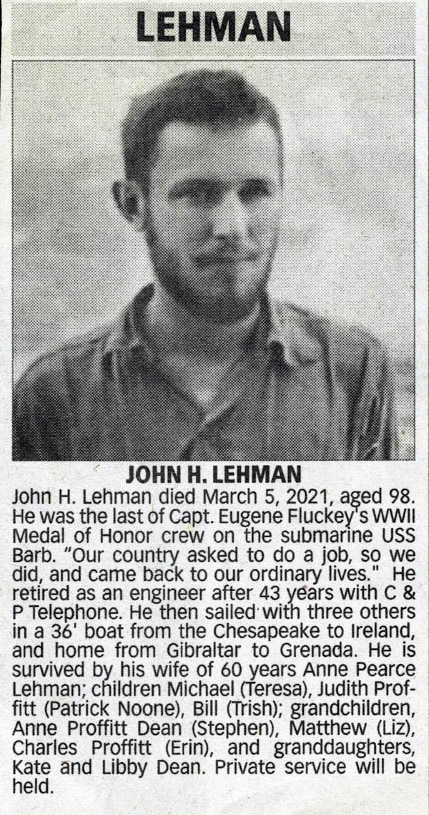

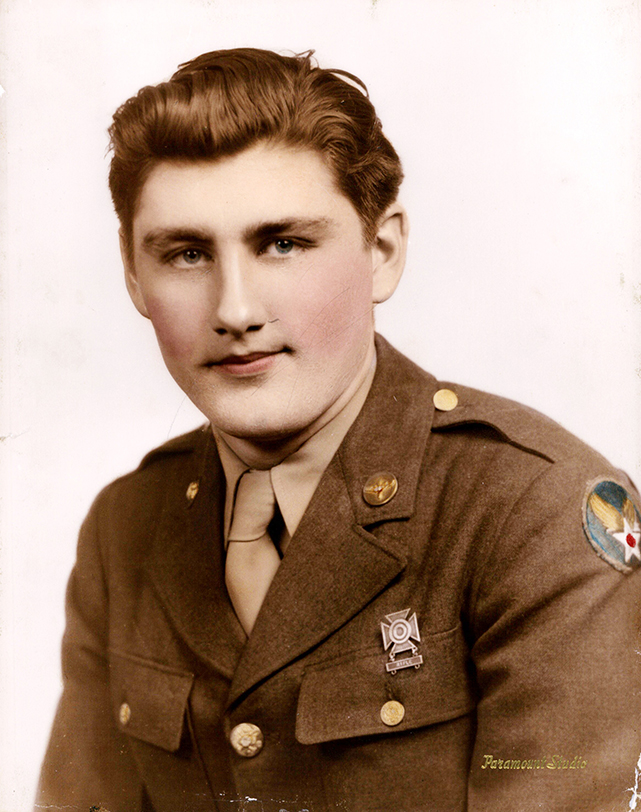

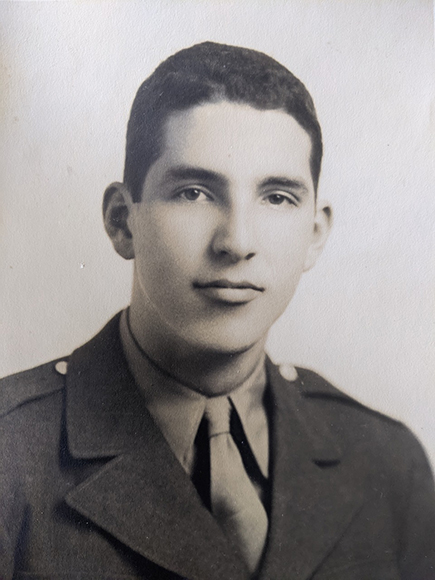

Clarence Deardorff Cullison, Jr.

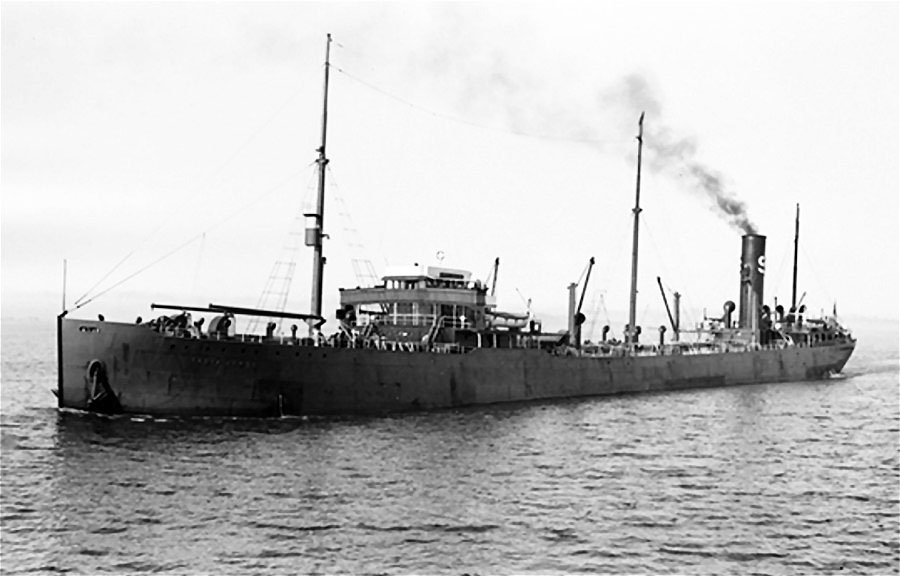

Liberation of Luxembourg

Gettysburg resident Clarence Deardorff Cullison, Jr. was born on September 20, 1918, in Franklin Township, Adams County, to parents Clarence Cullison, Sr. and Lena Cullison.

He had five brothers: Harvey, Oscar, Russel, Norman, and Chester Cullison; and five sisters: Margaret Cullison, Letha Myers, Mildred Plank, Kathryn Kepner, and Evelyn Spangler.

Cullison was married to his wife, Irene Mae Cullison (who passed away on June 3, 2004) for 66 years. The couple had two daughters and a son: Patsy Carey and her husband Ralph, Gettysburg; Nancy Richardson and her companion Raymond Kump, Gettysburg; and Ricky Cullison and his wife Lauren, Gettysburg.

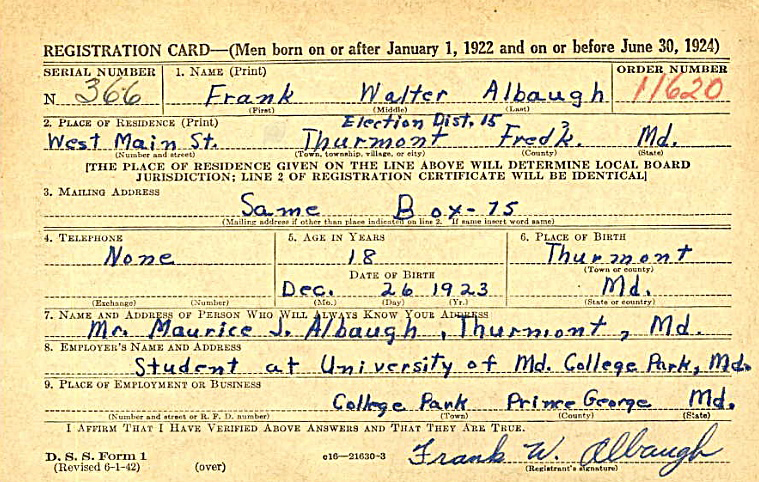

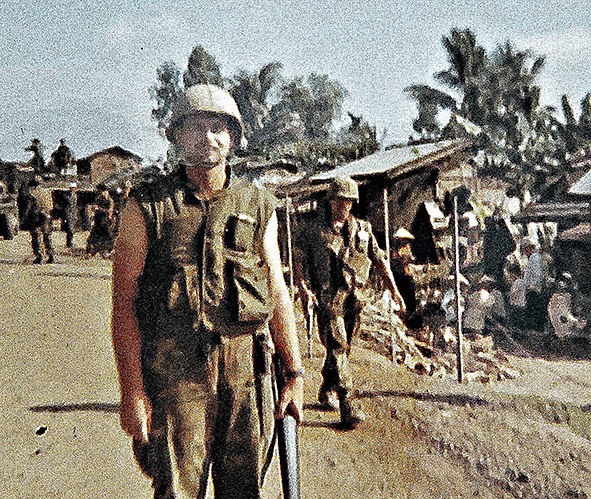

According to his enlistment records, he completed grammar school and had been employed as a general farmhand until his enlistment on May 19, 1944. Cullison was enlisted as a private into the United States Army at 22 years of age. At the time of his enlistment, he was 5’8” in height, weighed 145 pounds, and was employed at E.B. Romig, Biglerville, according to his November 5, 1948, Statement of Service.

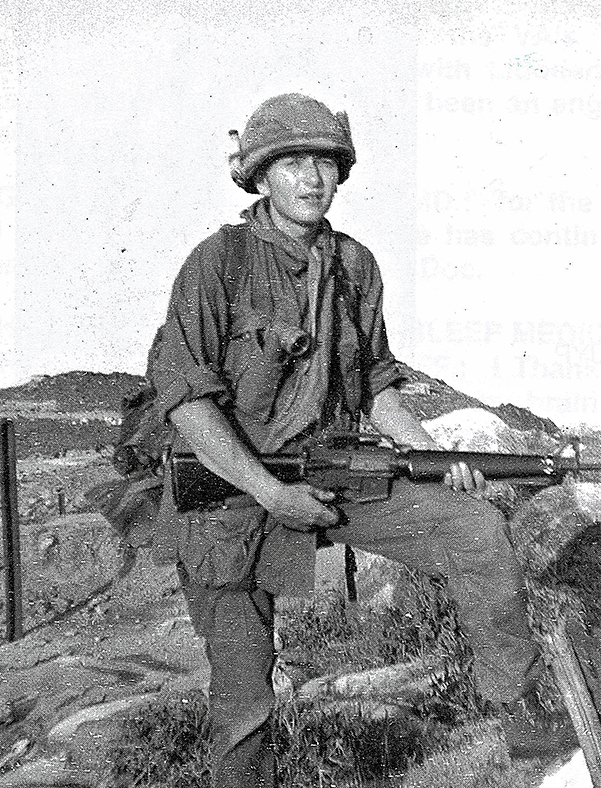

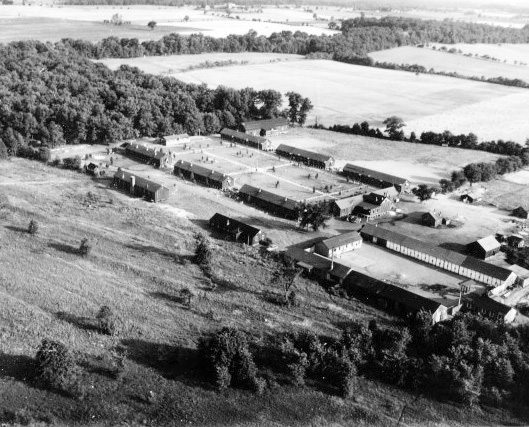

The New Oxford Item reported in an article regarding Cullison having been wounded-in-action that he had been employed, before being enlisted, at the Gettysburg Furniture Factory. Cullison received his basic infantry training at Fort McClellan, Alabama, before being dispatched overseas to the Luxembourg front, in time to participate in the “Battle of the Bulge,” also referred to, more officially, as the Ardennes Counteroffensive.

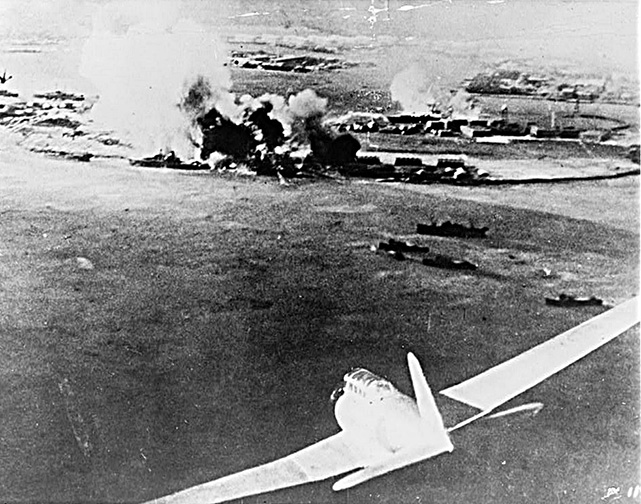

From December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945, the German Army attacked allied forces in a desperate measure to regain the ground in the Ardennes region of Belgium, France, and Luxembourg that had been lost to the allied forces. The German attack commenced on December 16, 1944, and raged on until January 25, 1945, when the German onslaught was stymied, as the result of the Battle of the Bulge.

The New Oxford Item, as well as other newspapers, reported on February 8, 1945, that Private Clarence D. Cullison, Jr. “was slightly injured in action in Luxembourg on January 17, according to a War Department telegram received February 1 by his wife who resides in Gettysburg…”

According to Cullison’s military medical record, he was admitted for treatment of his wound at a general hospital in January 1945. His medical records did not state if the general hospital was a public or military hospital. He was subsequently discharged from said hospital in February 1945. More specific dates were not provided, but if he had been wounded on January 17, he more than likely had spent several weeks in that medical facility.

According to his records, his diagnosis was determined to have been the result of having been struck in the head by shrapnel from an artillery shell, thereby causing a puncture wound which did not, at least, involve any nerve or artery involvement. Treatment entailed “penicillin therapy (treatment with penicillin).”

Prior to Cullison’s discharge from the Army, he had been promoted to Sergeant. As a result of his having been wounded, he was awarded the Purple Heart. For his service in the Army, he was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, and the European-African-Middle Eastern Service Medal with three Bronze Stars.

Following his discharge from the Army, Cullison was employed at Blue Ribbon Orchards, the Franklin Township Road Department, the Panel Factory, and with Barbour’s Fruit Stand on Route 30. Additionally, he also sold firewood and engaged in landscaping with his son for 21 years.

He was further employed at Musselman’s for 33 years as a shipping clerk, retiring from that position in 1982.

The (Baltimore) Evening Sun had reported in his obituary that Cullison was a lifetime member of the Cashtown Fire Company and the Biglerville American Legion, and that he was “an avid deer hunter,” and, additionally, he also enjoyed refinishing antiques and carpentry work with his brother, Oscar.

Cullison passed away at age 93 on Saturday, June 9, 2012, at his Gettysburg home. He was buried in the Biglerville Cemetery with full military honors, which were provided for by the Adams County Veterans Honor Guard, according to his obituary in The Sun.

Sergeant Clarence Deardorff Cullison, Jr.

The flag of Luxembourg flying from a Luxembourg hospital after its liberation by the American Army.