The British Invade catoctin mountain

by James Rada, Jr.

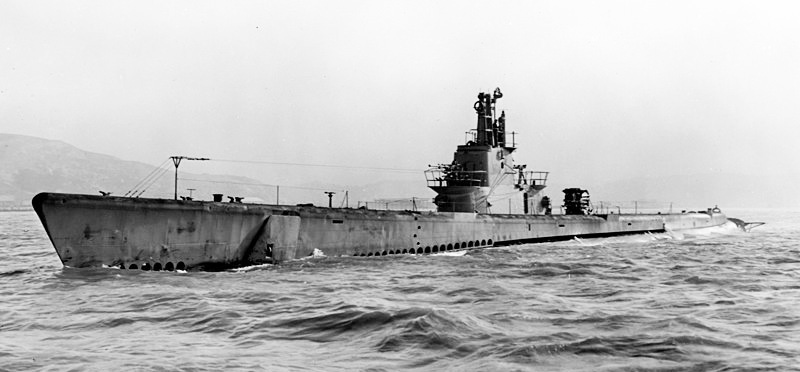

In the spring of 1941, the U.S. had yet to enter World War II, but other countries had been fighting for two years. Germany showed early dominance in the war, and it hadn’t been going well for the British Royal Navy. It had lost more than 55 ships and 18,000 men. Those who remained were exhausted.

“British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pressed the United States for desperately needed aid,” according to K.C. Clay in the report, “Rest Camp: A Report on the WWII Use of Catoctin Recreational Demonstration Area by the Royal Navy.” “Pushing to the edge of US neutrality, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought ways of helping the British.”

During March 1941, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act, which allowed the U.S. to aid the Allied nations with food, oil, and material. It was given free of charge, but it could only be given if the help was essential for the defense of the United States.

Under this act, the U.S. was able to justify repairing damaged Royal Navy ships. While the ships were in port, the crews went ashore to recuperate from the stress of combat.

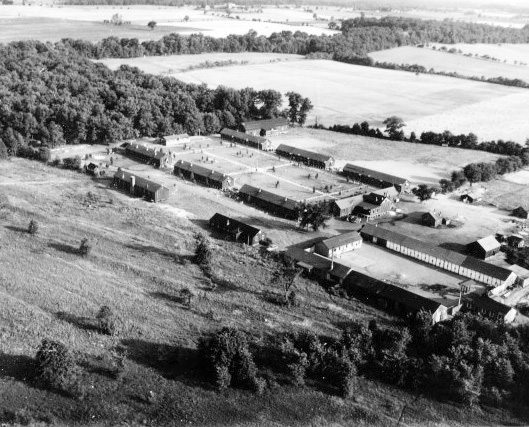

The Catoctin Recreational Demonstration Area on Catoctin Mountain was one of seven National Park Service sites that provided rest camps for the Royal Navy sailors. This pre-war U.S. aid to the Allies is largely unknown.

Clay, a National Park Service historian, identified four ships whose crews visited Catoctin Mountain. These were the H.M.S. Southern Prince, H.M.S. Bulolo, H.M.S. Menestheus, and H.M.S. Agamemnon.

During June, 150 sailors stayed at Camp Greentop in two groups of 75 men. Each group stayed for a week, enjoying swimming and other sports activities. Other sailors stayed at the Short Term Lodge, which the National Park Service had acquired after Bessie Darling was killed in the house in 1933. It was a 12-room boarding house with three indoor bathrooms.

“CRDA canceled visitor reservations for the summer of 1941 and configured the house to accommodate the sailors,” Clay wrote.

The largest group consisted of 85 sailors. In all, five groups of sailors stayed there averaging 56 men in each group.

The third site where Royal Navy sailors stayed was Hi-Catoctin. Two groups of sailors stayed there with an average size of 99 men.

As with just about everything that happened on the mountain which was supposed to be a secret, the truth was known to local residents.

“Although the British Ministry of Defense and the US War Department did not publicly acknowledge the presence of the sailors in the U.S., the residents of Frederick County were aware of them and extended invites to multiple social engagements,” Clay wrote. “National Park Service employees also provided social functions such as hot dog roasts and dances. To some of the war weary sailors, the Americans seemed over compensating for not being engaged in the conflict.”

This is not to say the British didn’t appreciate the efforts on their behalf. They repaid the kindness by putting on exhibition cricket and rugby matches for visitors to the park. They taught British songs, dances, and dialects to their hosts.

“Some sailors got on so well with the Americans that they married them,” Clay wrote.

Despite the camaraderie between the Americans and British, the British Admiralty had ordered the sailors not to talk about their assigned ship names, combat engagements, area of operation, and “any information that could possibly be used by the Nazis against them.”

The Nazis had sympathizers among the Americans who might have passed that information on.

Although locals knew of the Royal Navy presence, the U.S. media and the British press did not report on it until the U.S. Navy announced it on September 19, 1941.

After the successful 1941 season, plans were made for 1942, such as adding a telephone booth the sailors could use. However, the second season never happened because the U.S. entered the war and needed to use the facilities for its own purposes. It eventually served as a training camp for OSS agents and a rest camp for U.S. Marines.

Clay wrote that the rest camp story “is about the men who spent two years on alert for Nazi U-boats getting a week respite in the woods far inland from coastal waters. Some men arrived already decorated for valor. Others would go on to perform heroic actions. A few would sacrifice all within weeks of departing the camp.”

In total, more than 21,000 British sailors enjoyed a respite from the war on American soil, although only around 630 of them visited Catoctin.

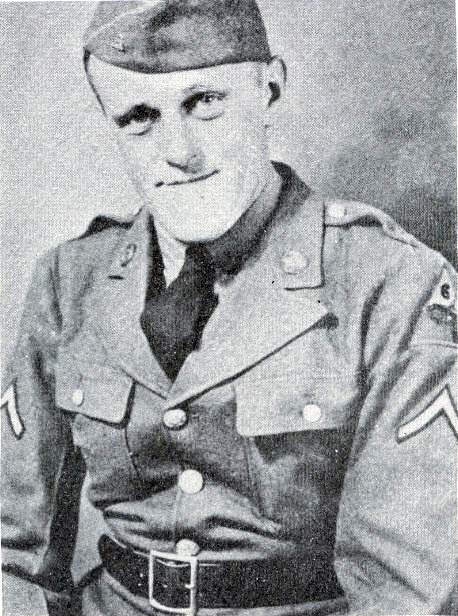

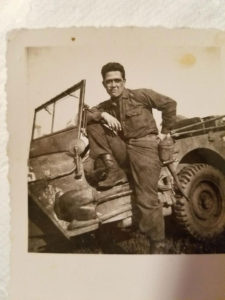

Picture shows a British sailor relaxing in a cabin on Catoctin Mountain during WWII.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

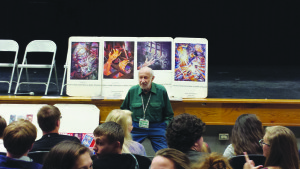

Holocaust Survivor, Mark Strauss, speaks with students at Catoctin High School about his personal experience and what it was like at that time in history.

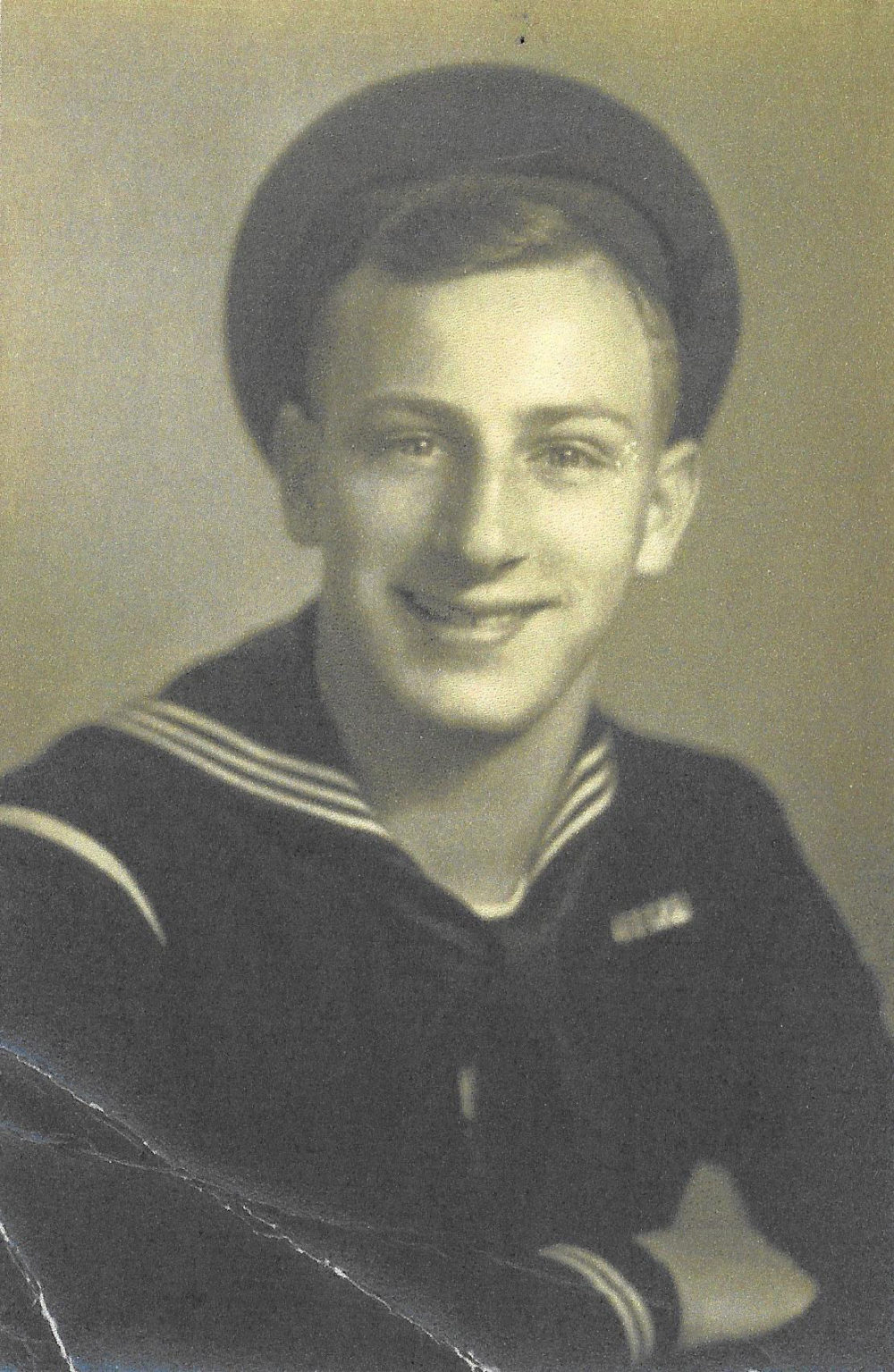

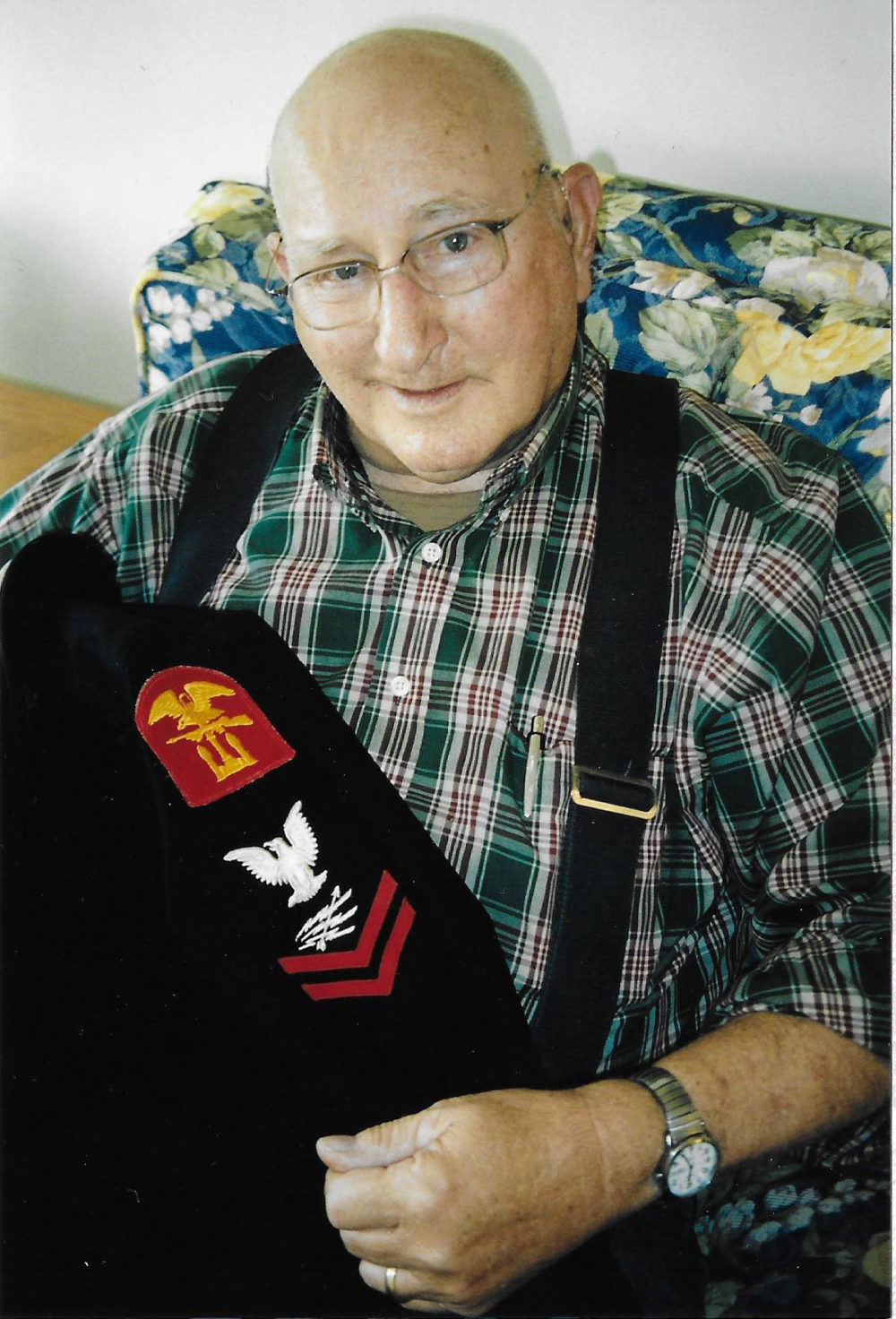

Holocaust Survivor, Mark Strauss, speaks with students at Catoctin High School about his personal experience and what it was like at that time in history. Born in 1927, at home in Emmitsburg to Gertrude and Hubert Joy, was a baby boy they named Joseph (Joe). Joe was one of eleven children: Bobby, Johnny, Kenny, Donald, Mike, Gloria, Patrick, Delores, Jerry, and Rosemary (passed away at three days old). Joe went to school at Saint Euphemia’s in Emmitsburg; he quit school at the age of fifteen and moved to Baltimore, Maryland. He went to work as a painter’s helper at S&A Williams, a painting contractor. He worked for them for about five years, when he decided to go work for his father, who went into business for himself. Joe liked to hunt and would make trips to Emmitsburg, where he would hunt rabbits, pheasants, and squirrel. He said he was not much of a deer hunter and has never killed one. He said he remembers his first automobile was a 1950 Pontiac. He stated that he doesn’t know how many cars he has had, but he’s still driving the one he bought in 1992, and at his present age of eighty-eight, he plans on driving as long as he is able.

Born in 1927, at home in Emmitsburg to Gertrude and Hubert Joy, was a baby boy they named Joseph (Joe). Joe was one of eleven children: Bobby, Johnny, Kenny, Donald, Mike, Gloria, Patrick, Delores, Jerry, and Rosemary (passed away at three days old). Joe went to school at Saint Euphemia’s in Emmitsburg; he quit school at the age of fifteen and moved to Baltimore, Maryland. He went to work as a painter’s helper at S&A Williams, a painting contractor. He worked for them for about five years, when he decided to go work for his father, who went into business for himself. Joe liked to hunt and would make trips to Emmitsburg, where he would hunt rabbits, pheasants, and squirrel. He said he was not much of a deer hunter and has never killed one. He said he remembers his first automobile was a 1950 Pontiac. He stated that he doesn’t know how many cars he has had, but he’s still driving the one he bought in 1992, and at his present age of eighty-eight, he plans on driving as long as he is able. Joe met Betty Ruth Luster, who lived across the street from where he was residing in Baltimore, and they later were married. Betty and Joe had three children: two girls and one boy—Karen, Kathy, and Steve. They raised their family in southwest Baltimore, close to St. Agnes Hospital. Betty passed away at the age of seventy-three from cancer while they were living in a basement apartment at their daughter’s house. Their daughter was a nurse and was helping to take care of Betty. Joe’s daughter was murdered by a male friend of hers, and Betty died about three months later. The house was sold, and Joe went to live with his son, Steve, for three months; Steve’s house wasn’t large enough to accommodate everyone. Joe has resided (for the past six years) in that area at an apartment complex run by Catholic charities, called DePaul House.

Joe met Betty Ruth Luster, who lived across the street from where he was residing in Baltimore, and they later were married. Betty and Joe had three children: two girls and one boy—Karen, Kathy, and Steve. They raised their family in southwest Baltimore, close to St. Agnes Hospital. Betty passed away at the age of seventy-three from cancer while they were living in a basement apartment at their daughter’s house. Their daughter was a nurse and was helping to take care of Betty. Joe’s daughter was murdered by a male friend of hers, and Betty died about three months later. The house was sold, and Joe went to live with his son, Steve, for three months; Steve’s house wasn’t large enough to accommodate everyone. Joe has resided (for the past six years) in that area at an apartment complex run by Catholic charities, called DePaul House.

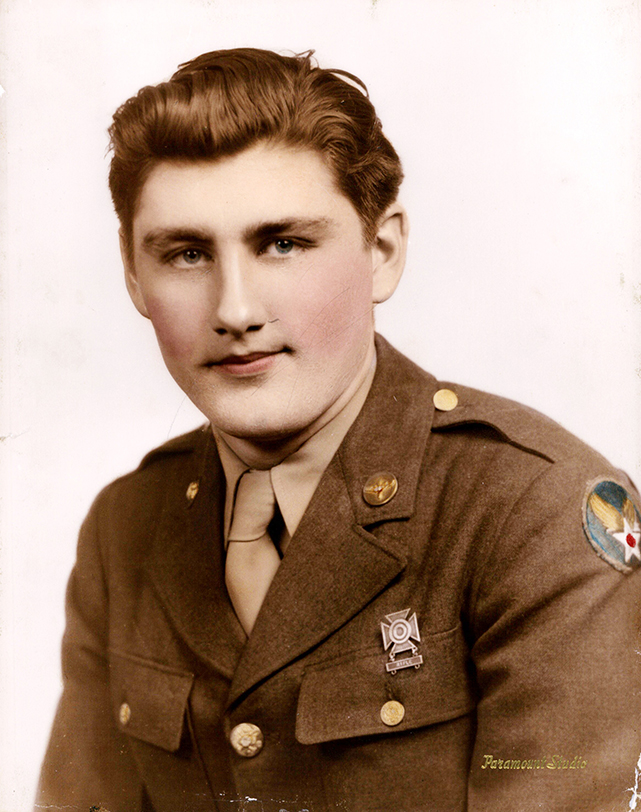

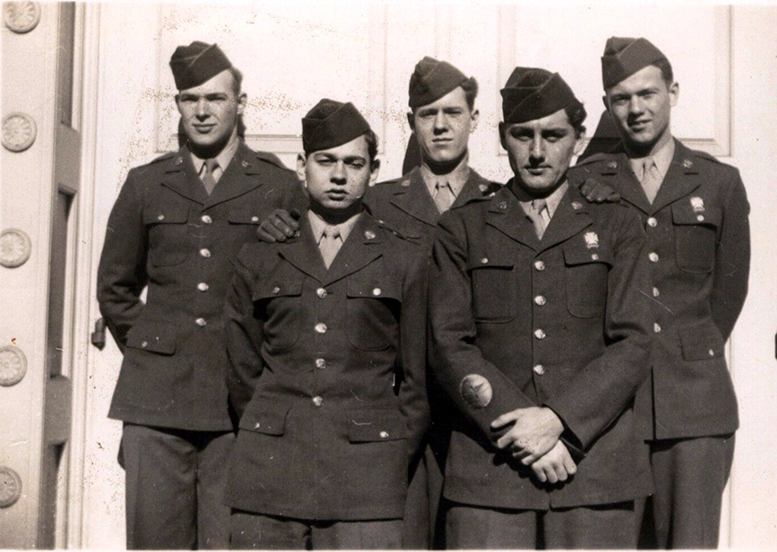

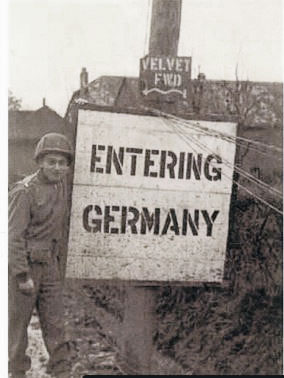

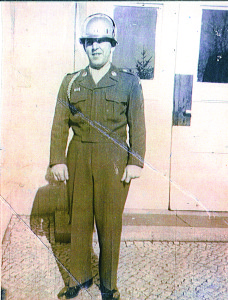

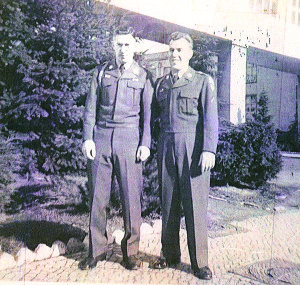

Donald Lewis stood crammed among a group of friends and fellow soldiers, trying not to lose his balance. The landing craft they were on was pushing toward its destination on Omaha Beach at Normandy, France. A strong current threatened to pull them away from their destination.

Donald Lewis stood crammed among a group of friends and fellow soldiers, trying not to lose his balance. The landing craft they were on was pushing toward its destination on Omaha Beach at Normandy, France. A strong current threatened to pull them away from their destination. Lewis also had a political career. He served two terms as Mayor of Thurmont and one term as a Frederick County Commissioner. He said a group of people tried to talk him into running for governor, but he turned them down, saying, “I’m too honest for that.”

Lewis also had a political career. He served two terms as Mayor of Thurmont and one term as a Frederick County Commissioner. He said a group of people tried to talk him into running for governor, but he turned them down, saying, “I’m too honest for that.”