Roaring fires helped keep Isaac Cromer’s house and outbuildings warm during the cold January days in 1909. On January 25, Isaac and his wife, Catherine, got called away to Gettysburg to care for Cromer’s mother-in-law. That left 20-year-old John Cromer alone on the farm that was located in Adams County between Littlestown, Pennsylvania, and Silver Run, Maryland.

While John Cromer was doing some work on the farm, stray sparks spewed from the chimney of an outbuilding and caught the newly remodeled farmhouse on fire. The house had originally been a log cabin, but when it was remodeled, clapboard had been placed on the exterior. Also, a large porch had been added to the front of the house and an addition built onto the rear.

When Cromer saw the fire, he began rushing around to try and extinguish the flames. He was working by himself, though, and was soon losing ground as the fire spread.

“Realizing that the house was doomed if he could not secure help, he ran to the telephone, called the central at Littlestown and telling her what was wrong asked that she notify all his neighbors having telephones that assistance was wanted at once. Many of the farmers in that vicinity are on a rural telephone line and Littlestown exchange called all and soon had a small army of fire-fighters on the scene,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

Rural phones at the time used a hand crank to produce enough power to ring the bells of all the telephones on the line and alert the central operator. This multiple ringing of phones, though annoying if the call wasn’t for you, could allow for quick notification of multiple people at once, which was just what Cromer needed.

The group of neighbors that turned out to fight the fire didn’t make any better headway in saving the house, either. The flames were spreading too quickly. Once they realized this, they concentrated instead on saving the contents of the house.

They rushed into the house and carried out furnishings, clothing, and personal effects out of the house. Because of their efforts, the newspaper reported that little, if anything, that was movable was lost in the house.

“The fact that his loss was not made greater by fire loss of the contents of the building and the probably destruction of other buildings was due to the quick work of the son and the Littlestown exchange in summoning aid which proved most effective and valuable,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

The house loss amounted to several thousand dollars, which is equivalent to about $175,000 in today’s dollars.

It could have been much greater, though, had it not been for Cromer and the Littlestown central operator realizing the power of the telephone.

The country had more than three million telephones at this time that were connected with central switchboards like the Littlestown exchange. However, the majority of these phones were located in big cities. Rural areas had to make do with having multiple homes in a farming community all using the same phone line. Some farming communities were even known to use their barbed-wire fencing as telephone line to transmit signals.

Little remains today that would suggest the size of the hatchery operation that once existed until the early 1950s. A sign on Fish Hatchery Road, off U.S. 15 south, states: “Lewistown Trout Hatchery and Bass Ponds Frederick County – Purchased by State 1917” (shown right).

Little remains today that would suggest the size of the hatchery operation that once existed until the early 1950s. A sign on Fish Hatchery Road, off U.S. 15 south, states: “Lewistown Trout Hatchery and Bass Ponds Frederick County – Purchased by State 1917” (shown right).

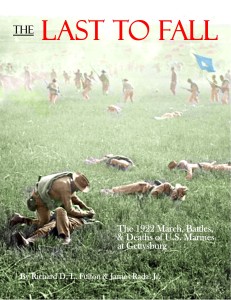

Richard D. L. Fulton and James Rada, Jr. will be holding a book siging at St. Philomena’s on the Emmitsburg Square in April.

Richard D. L. Fulton and James Rada, Jr. will be holding a book siging at St. Philomena’s on the Emmitsburg Square in April. As the Confederate Army retreated from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863, they encountered Union troops in the area of Blue Ridge Summit. A two-day battle ensued in the middle of a thunderstorm that eventually spilled over the Mason-Dixon Line into Maryland.

As the Confederate Army retreated from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863, they encountered Union troops in the area of Blue Ridge Summit. A two-day battle ensued in the middle of a thunderstorm that eventually spilled over the Mason-Dixon Line into Maryland.