From Iran to Gettysburg

by Richard D. L. Fulton

Photo Courtesy of Howard’s daughter, Coleen Reamer

Pvt. Howard Mace appears second from the left in this photograph, taken in the Middle East.

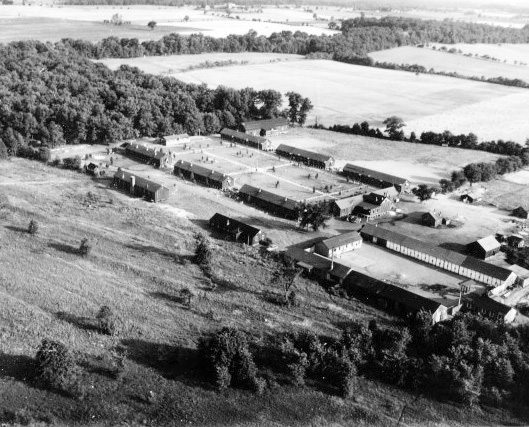

Photo Courtesy of National Park Service, Gettysburg

Photographed is Camp Sharpe.

Private First Class Howard Mace’s career in the Army during World War II found him guarding supply convoys carrying supplies through Iran to Russia, bombs being shipped from Virginia to New York, and 400 German POWs on the Gettysburg Battlefield.

Mace, who was born in Medix Run, Pennsylvania, was 30 years of age and working at the U.S. Naval Shipyard in Philadelphia when war was declared against Japan and Germany in 1941. Although he could have been granted a deferment, he decided to enlist in the Army in April 1942, serving in the 1325 Service Command Unit as a military policeman.

After completing basic training in 1942, he and his unit were deployed in 1943 to the Middle East (Iran area), where the unit guarded supply convoys heading through Iran to the Russian allies, where the unit remained on duty until early 1945. In early 1945, Mace was dispatched to Norfolk and, subsequently, was assigned to guard convoys delivering bombs to military installations in New York City.

Soon thereafter, Mace was reassigned to assist with guarding around 400 German soldiers and officers being held at Camp Sharpe (formerly a Civilian Conservation Corps camp) on the Gettysburg Battlefield. The CCC camp had been converted into a special forces training base in 1944 and was renamed Camp Sharpe. (See German POWs helped save Adams’ Agriculture in this issue of The Catoctin Banner). Mace’s primary role at Camp Sharpe was to guard the prisoners when they were outside of the compound on work details in the farm fields, orchards, and canning factories.

Mace’s daughter, Coleen Reamer, a Hamiltonban Township supervisor, said her father didn’t talk much about the war to her but did occasionally discuss the war with her brother, Ronald.

Reamer informed that her father said that “he liked that duty (guarding the PWs – POW was a post-World War II designation) very much because the prisoners did all the cooking, cleaning, polishing and had no desire to go anywhere since they were treated so well.” He stated that Gettysburg, like the rest of the country, was under food rationing, but the POW camps were not.

Reamer reported that guards and military staff could invite guests to visit the camp and the prisoners generally prepared the meals. “Because the camp had plenty of otherwise rationed items, the townspeople enjoyed being invited to the camp for a tour and dinner,” she said her father observed.

Reamer said, “The belief by Americans was that if we treated German POWs well, then that would hopefully translate the same for our American POWs held by the enemy overseas.”

Only a few prisoners attempted escapes were ever reported from the three German prisoner-of-war camps that were built on the Gettysburg battlefield. Two escaped the Emmitsburg Road camp but surrendered to a family wife and her daughter-in-law in York. Another escaped one of the other camps but surrendered to a New York City book dealer. Two others escaped and were caught at Zora (on Waynesboro Pike).

Reamer said her father did mention an escape in which two of the German prisoners slipped away from a work detail and were found sitting at the Gettysburg Town Square. They only wanted to see a movie, but the Strand Theater on Baltimore Street refused to accept PW canteen script for admission.

Mace served at Camp Sharp until he was mustered out on November 7, 1945. He was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, and the European-African-Middle East Campaign Medal.

He married his wife Jo-Ellen Anna Nary in 1946, and they had four children: Coleen Reamer, Ronald Mace, Vikki Mace, and Beth Vivaldi.

(Reporters Note: Mace likely would have been at the Camp Sharpe compound when the Army suffered its only casualty that would occur in conjunction with the prisoner-of-war camps at Gettysburg. On September 1, 1945, when a shot rang out in Camp Sharpe, guards fanned out to locate the source and found the body of Private First-Class Joseph Ward, lying lifeless on the floor of one of the guard towers; they saw that he had been shot. It was subsequently ruled that his death was a suicide.)