Richard D. L. Fulton

The Gettysburg Battlefield served as the home to America’s first all-black Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in 1939, whose recruits helped in making improvements to the old 1863 former combat site of a fierce and brutal war.

The CCC was established in 1933 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as part of his “New Deal,” a conglomerate of measures initiated by the president in his efforts to address the ongoing “Great Depression.”

The CCC was established in order to provide skill training, work, clothing, and food for what would, at the height of the program’s existence, involve some three million participants (300,000 recruits and the balance thereof being individuals employed in related roles). Participation was limited to unemployed, unmarried men, ranging in age from 18 to 25. Participants were paid $30 per month, of which $25 was sent to each participant’s dependent (if any).

Numerous CCC camps were established throughout the nation and its territories. The War Department managed the program and provided the camp officers.

Black participation was limited to 10 percent, and these participants were allocated to (usually) all-black camps under the command of white officers. Of the three million enrollees (the National Park Service [NPS] maintains the number was two million), only about 200,000 blacks were accepted into the CCC.

The CCC focused its labor force on improving primarily public lands, forests, and parks, which, due to the amount of tree plantings and landscaping work in which they were employed, led to the participants being called “Soil Soldiers.”

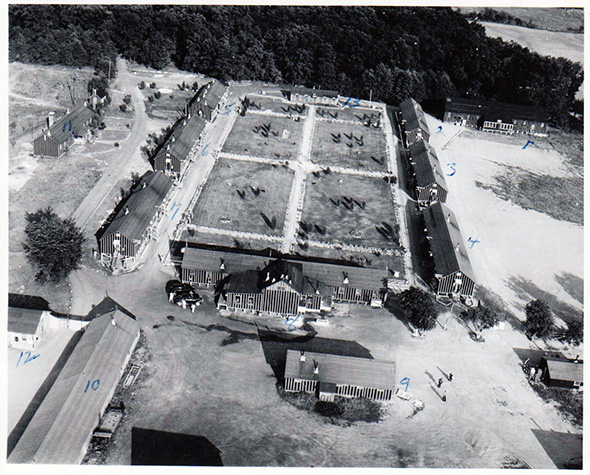

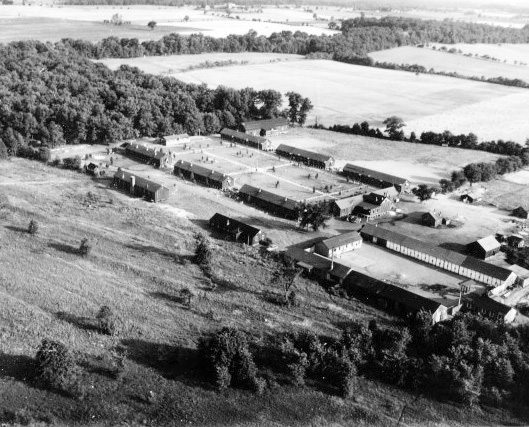

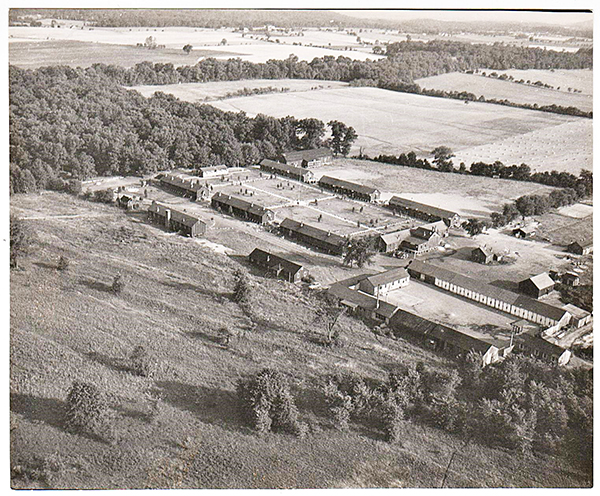

The CCC established two camps on the Gettysburg battlefield. The first camp was located in 1933 in Pitzer Woods (in the field behind the site where the General Longstreet monument stands today) and designated it NP-1. The second camp was located in McMillan Woods in 1934, on the western slope of Seminary Ridge, taking its access off West Confederate Avenue, and designated it NP-2.

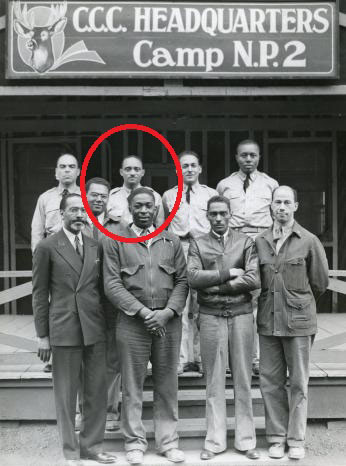

After the Pitzer Woods camp had been abandoned in 1937, the last remaining CCC camp, McMillan Woods, was about to make history when it was announced in late 1939 that the camp (which then housed about 198 recruits) was to become the first all-black camp in the country, which included the officers.

As the transition of the McMillan Woods camp to be an all-black camp became a reality, the camp’s first black commander, 1st Lieutenant George W. Webb, reported for duty on November 12, 1939.

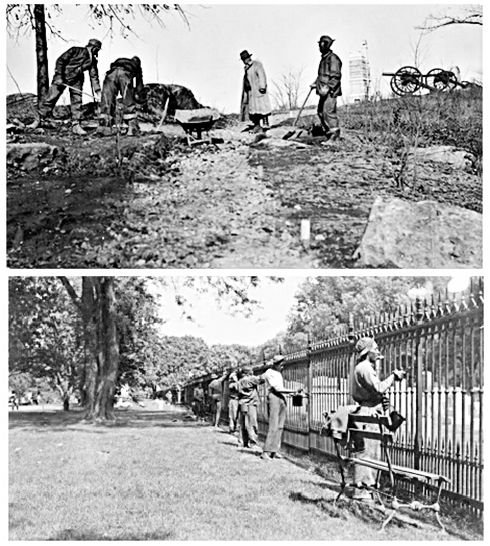

Types of work performed by the CCC (including the work of the recruits of Pitzer Woods and McMillan Woods) on the Gettysburg Battlefield included (as amassed via several newspaper sources and others, principally the NPS):

Cleaning existing battlefield wells and installing casing to existing wells that lacked them;

Improving/installing water pipelines (to help improve water distribution to the battlefield facilities and battlefield farms, and for drinking fountains);

Installing new fountains and fire hydrants,

Constructing stone bridges over battlefield creeks;

Establishing and/or improving foot-paths, trails, and bridle trails;

Groundskeeping, including planting and pruning trees, cutting and hauling wood, removing stumps, and lawn maintenance;

Erecting 25 miles of stone walls and installing iron fencing (after having removed “modern” fencing);

Snow shoveling as needed, and assisting on and off-site with any help needed regarding flood and fire control efforts;

Reconstructing earthworks and other battle-related features and cleaning monuments:

Resetting grave markers in the National Cemetery; and

Engaging in countless tasks as needed, including serving as battlefield guides during the 75th Battle of Gettysburg anniversary celebrations in 1938.

Despite all the contributions the recruits at the McMillan Woods camp had made by improving the Gettysburg battlefield during their occupancy, it was decided to close the camp in 1942. The Gettysburg Times reported on March 6, 1942, that a telegram emanating from the CCC’s regional headquarters in Virginia stated, “Due to further reductions in CCC camps” that the McMillan Woods camp had been “approved for abandonment on or about March 15.”

Camp Commander Webb had left for reassignment in August of 1941. The camp commander at the time of the closure was Lieutenant Philip Atkins.

There’s no doubt the demand for troops to serve in the fight against the Germans and Japanese had readily depleted the number of adult males that might have otherwise been available for CCC service.

Although the buildings of the CCC camp were abandoned, the structures would remain to address additional projects as needed.

In January 1944, the McMillan Woods camp, which had been abandoned for over two years, saw renewed life as hundreds of trainees out of Camp Ritchie arrived on a secretive mission preparatory to D-Day operations.

These were the men of the Mobile Radio Broadcasting company, a quasi-military propaganda force that had come to be collectively referred to as the “Ritchie Boys.” Upon occupation by the Ritchie Boys, the camp was renamed Camp George H. Sharpe (also known more simply as Camp Sharpe, and less known by its more formal name, Psychological Warfare Training Center).

Leon Edel, a member of one of the Mobile Radio Broadcasting companies, noted in his book, entitled The Visitable Past: A Wartime Memoir, that the camp had not weathered well during its two years of abandonment. He wrote that the old CCC barracks appeared as though they had been built and “were filled with dust and cobwebs. The windows looked as if mud had been smeared across them. Mice and rats had left their deposits.”

Arthur H. Jaffe, captain of the Second Mobile Radio Broadcasting Company, described in his History Second Mobile Radio Broadcasting Company, December 1943-May 1945, that Camp Sharpe was “rugged and barren,” noting that, “The company was quartered in former CCC barracks that were surrounded by a sea of mud. The wind whistled through gaps in the walls while four stoves tried in vain to keep up the room temperature.”

The old CCC camp was again abandoned in 1944 after the Mobile Radio Broadcasting companies were dispatched to Europe in time to participate in D-Day.

But the camp would not be re-abandoned for long. Due to the tremendous drain on manpower, agriculture in Adams County and throughout the country was imperiled due to a lack of available help to manage harvesting and canning food products. Through the exhaustive efforts of local and county farming associations, such as the Adams County Emergency Farm Labor Committee, help was on the way via the War Department, and in the form of hundreds of German prisoners of war.

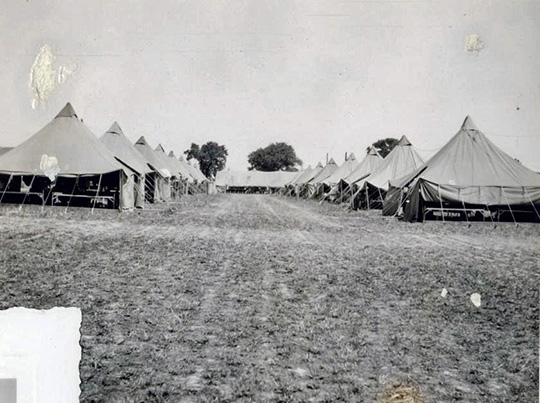

A tented camp was initially established along Emmitsburg Road to hold 400 prisoners towards the end of June, but the intent was to transfer the prisoners (as well as a few hundred additional POWs) to the McMillan Woods CCC camp. So, in November 1944, the twice-abandoned camp was re-occupied… this time by former enemy combatants (a second prisoner of war camp was established nearby, fronting on West Confederate Avenue and housing an additional 400 German prisoners).

After the end of World War II, the Germans were repatriated (sent home), a process that was not actually fully completed until July 1946.

The final demise of the old CCC camp, which had certainly experienced its share of making history and/or participating in the making of history—from serving as the home to the first all-black CCC camp to serving as the training site for propaganda units bound for Europe in World War II, to housing ultimately some 800 German POWs to assist in saving local agriculture—came in September-October 1947.

The (Hanover) Evening Sun reported on September 25, “Termination of the Adams County Emergency Farm Labor program and the request of the National Park Service (NPS) to restore the grounds now occupied by Camp Sharpe presents an opportunity for farmers to have first consideration in the disposal of the buildings and equipment and it may be possible to salvage buildings in such a manner that reassembling will be possible.”

On October 9, all of the camp buildings (which by then had amounted to some 22 buildings), and all of the remaining furniture contained within them, along with stoves, plumbing, and electrical fixtures, were auctioned off, fetching a total of approximately $8,700, according to the October 10 edition of The (Hanover) Evening Sun.

Photo Courtesy of the National Park Service CCC recruits work on various projects on the Gettysburg battlefield.