by James Rada, Jr.

When the men of the Thurmont District of Frederick County began returning home from World War I, they were feted with a parade through Thurmont. People lined the streets to see their returning heroes. They cheered, and they cried.

In that, Thurmont was not unusual. Just about every town in the country celebrated its returning soldiers from The War to End All Wars.

It wasn’t enough for Thurmont, though. Some citizens realized that those who had given the most weren’t there to march in the parade. Eleven men from the district had died in the fighting of World War I.

Rosa Waters, whose son James died from Spanish Flu while serving in the military during the war, led a community group that wanted to create a lasting memorial to the town’s servicemen.

The Grimes Estate donated a piece of land on East Main Street for a memorial park. Ground was broken in the spring of 1922, and “The work of transforming the meadow into Memorial Park was begun and there will be no let-up until it is finished,” reported the Catoctin Clarion.

Committee members began soliciting donations for the landscaping and construction work of the park. More than $3,000 was raised (around $44,000 in today’s dollars), which more than paid for the initial expenses of the park.

On Armistice Day 1922, a parade that included Veterans and students from Thurmont High School marched through Thurmont. “The town was in holiday attire for the occasion. Flags were displayed from every business place and private home, many of the private homes becoming elaborately decorated with the national colors,” the Frederick Daily News reported.

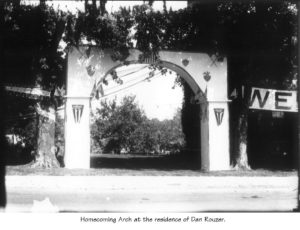

The parade passed under the stone arch that marked the entrance to the park. Hundreds of citizens watched the parade pass and then followed it to the park.

The speakers and special guests sat on the rostrum, which had been built from native stone. Surrounding the rostrum were eleven scarlet oaks that had been planted in memory of the young men who had died in the war. They were: Louis R. Adams, Murry S. Baker, Benjamin E. Cline, Edgar J. Eyler, William T. Fraley, Roy O. Kelbaugh, Jesse M. Pryor, Clifford M. Stitely, Raymond L. Stull, Stanley M. Toms, and James S. Waters.

The park also featured four bronze tablets, three of which had names of Thurmont Veterans inscribed on them. The widow of Lt. Edgar Eyler, who had died in the war and for whom the Thurmont American Legion was named, unveiled the tablets.

The Frederick Daily News reported that “Frederick County’s first memorial to war heroes and the first in the state it is said, was dedicated with appropriate and interesting ceremonies at Thurmont Saturday morning.”

One of the speakers at the event was Folger McKinsey, the “Bentztown Bard.” He told the crowd, “You have paid more attention to Armistice Day than any other town in the state; you have great reason to be proud of yourselves.”

He also read a poem inspired by the event that was published in the Baltimore Sun a few days later. It read in part:

And they shall turn and read these carven names,

And they shall see again the battle-flames,

And tell again the story of the strife

And gaze again as if across the seas

To those old fields of Flanders and Argonne,

The poppied fields, the shattered Picardy,

Belleau and Meuse – and be so glad that we

In our own time of golden memory,

Looking beyond the tumult and the wave,

Have planted here this tribute to the brave,

The true, the fine, the noble and the fond!

George Wireman noted in his book, Gateway to the Mountains, “Although the memorial was a community project, it did not officially become a part of community property until November 11, 1928, when it was turned over to the Town Commissioners and accepted on behalf of the citizens, by Mayor Frank L. Cady.”

The park continues to serve Thurmont today as a memorial to its sons and daughters who serve in the Armed Forces.

The undated photo is believed to be from the end of WWI, but it may show the original arch entry for Memorial Park.