The Birth of the Interstate

Richard D. L. Fulton

Military convoys carrying troops and war supplies were not a rare sight in Frederick County and elsewhere during World War I but were certainly nothing like the vision that local residents would be witnessing in July of 1919.

The Catoctin Clarion announced on June 19, 1919, that the largest military convoy that had ever been assembled in the United States was about to be launched on a great experiment to determine how easily such a convoy could potentially travel from the East Coast to the West Coast, utilizing whatever route would be deemed the most expeditious.

“Plans were completed today (June 14) by the (Army) Motor Transport Corps for the first transcontinental trip of an army motor-truck train (convoy),” the newspaper reported, further noting “It will start from Washington (D.C.) July 7, and end at San Francisco from 47 to 60 days later.”

The Clarion reported that the convoy would consist of 35 assorted military trucks, two ambulances, six motorcycles, two tank-trucks, two kitchen trailers, two water-tank trucks, one engineer-shop truck, one office-work truck, one search-light truck, and five passenger cars. The Harrisburg Telegraph reported on July 2 that 209 officers and men would be aboard the convoy. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on July 9 that the number of men in the convoy was more than 250.

One of the main challenges of the trip, the newspaper noted, was to “preserve intact, the entire convoy train throughout the movement from start-to-finish,” and would not be allowed to depend on any “outside assistance” for any help, other than for supplying fuel, oil, and water. The convoy would follow the Lincoln Highway as much as possible, except only for detours.

On the first leg of its journey to the Pacific, the convoy would depart from Washington, D.C., strike across Maryland to Frederick County, then north to Gettysburg, and from there, proceed westward.

The convoy left Washington, D.C. on July 7, having made good time reaching Frederick where the troops encamped on the first night, and then swung north on July 8 towards Emmitsburg.

The first major problematic issue occurred when the convoy reached the covered bridge that carried South Seton Avenue over Toms Creek in Emmitsburg on the morning of July 8, an event that proved so challenging that the encounter literally, ultimately, inspired the creation of the Interstate Highway System.

It was quickly discovered that only a few of the military vehicles could even cross the bridge due to the vehicles’ heights or weights. To complicate matters further, only a few vehicles were found to be capable of fording the creek, and the majority scattered in all directions to try and find an alternate route to bypass the old South Seton bridge.

Finally reuniting north of Gettysburg, the convoy immediately encountered another covered bridge over Middle Creek, which presented the same issues regarding the ability of the convoy to cross it. However, in this instance, the vehicles were able to ford the creek at this location.

The two bridge delays resulted in the convoy—that had reached the Emmitsburg bridge around 7:00 a.m.—not reaching Gettysburg until 1:00 p.m.

The Gettysburg Times reported in their July 9 issue, that a Lieutenant Shockey (identified only as being one of the officers within the convoy) stated, “These old wooden bridges are a thing of the past and it wouldn’t be a bad idea to run over them and break them down to show how poorly they are constructed.”

Among the officers present—who were not the least bit humored by these two experiences—was Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower, who remembered the misadventure, credited his experience at the South Seton bridge as having ultimately inspired his effort to create an interstate highway system.

On June 29, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act into law, thereby effectively creating the Interstate Highway System (also known as the National Highway System).

As to the fate of the old 1919 convoy… the convoy arrived in San Francisco at the end of their 62-day trek. Along the way, 21 members of the convoy lost their lives. Only eight vehicles were lost.

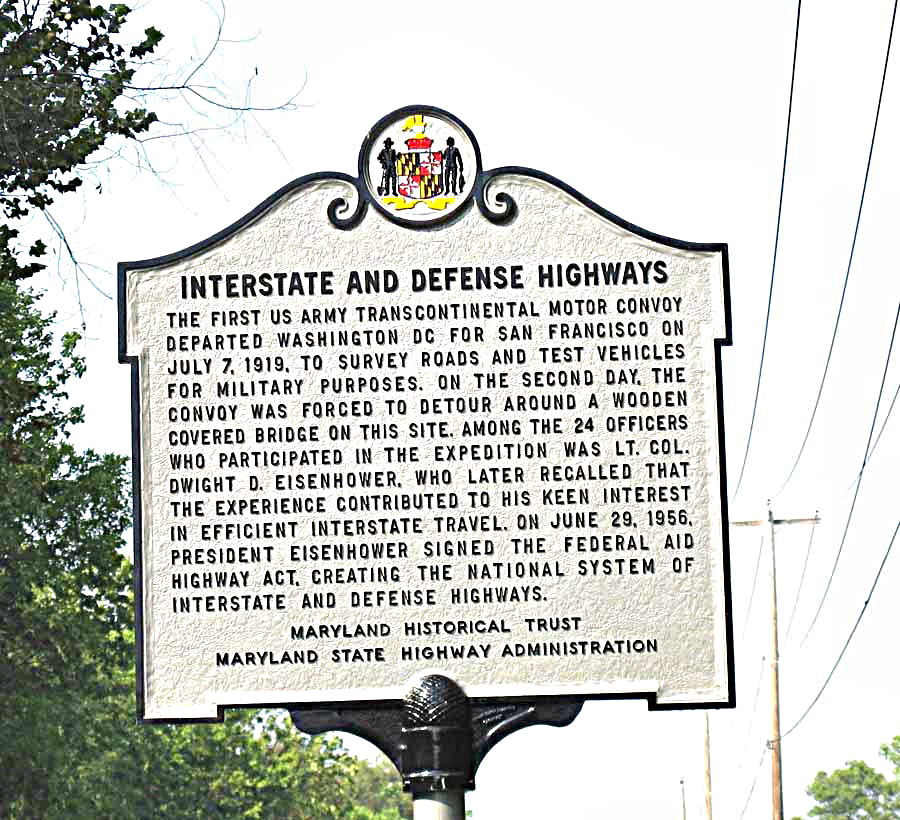

On June 28, 2006, the Maryland State High Administration unveiled a historic placard at the site of the infamous 1919 crossing at Toms Creek, in conjunction with the 50th Anniversary of the founding of the National/Interstate Highway System.

Preparations made by State Highway Administration for the 2006 50th Anniversary Commemoration of the Interstate Highway System. The event included a reconstruction of a covered bridge over Toms Creek.

Historic Marker located at the site of the former South Seton Covered Bridge.

Frederick County hides a wealth of natural resources underground. It is mined for iron, copper, gold, lead, silver, zinc, aluminum, stone, limestone, silica, calcium, and clay. At one time, Frederick County also had a short-lived coal mine or did it?

Frederick County hides a wealth of natural resources underground. It is mined for iron, copper, gold, lead, silver, zinc, aluminum, stone, limestone, silica, calcium, and clay. At one time, Frederick County also had a short-lived coal mine or did it?

Thurmont’s stop on the Western Maryland Railway makes up only a paragraph in the history of the railroad. For Thurmont, however, it was a major event that not only helped shape the town’s future but also gave it its unique name.

Thurmont’s stop on the Western Maryland Railway makes up only a paragraph in the history of the railroad. For Thurmont, however, it was a major event that not only helped shape the town’s future but also gave it its unique name. Sallie K. Harrison-Boyce-Auginbaugh-Boyce may have never figured out exactly what she wanted in a husband, but she certainly knew what she fancied from a house. In early 1902, the Catoctin Clarion and Star and Sentinel, published “A Matrimonial Mix,” an article explaining how Sallie Boyce first married and divorced a man named Harrison, wed Harrison’s new wife’s father, surname Boyce, to be left a widow, and lastly wed Thurmont’s Water Street Jeweler Eber E. Auginbaugh. Marital mishaps aside, Sallie’s union to Auginbaugh brought Thurmont its most unique and recognizable residence, located at 513 East Main Street.

Sallie K. Harrison-Boyce-Auginbaugh-Boyce may have never figured out exactly what she wanted in a husband, but she certainly knew what she fancied from a house. In early 1902, the Catoctin Clarion and Star and Sentinel, published “A Matrimonial Mix,” an article explaining how Sallie Boyce first married and divorced a man named Harrison, wed Harrison’s new wife’s father, surname Boyce, to be left a widow, and lastly wed Thurmont’s Water Street Jeweler Eber E. Auginbaugh. Marital mishaps aside, Sallie’s union to Auginbaugh brought Thurmont its most unique and recognizable residence, located at 513 East Main Street.