The Day the South Won

Richard D. L. Fulton

Based on The Last to Fall: The 1922 March, Battles, & Deaths of U.S. Marines at Gettysburg by Richard D. L. Fulton and James Rada, Jr.

We have all been taught that the South “lost” the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, fought when the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, under General Robert E. Lee, collided with the Union Army of the Potomac, under General George Meade.

While one could argue ad infinitum the validity of declaring the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg a Confederate defeat, Confederate forces did, in fact, defeat the Union forces and win the Battle of Gettysburg on that hallowed ground—only 59 years too late.

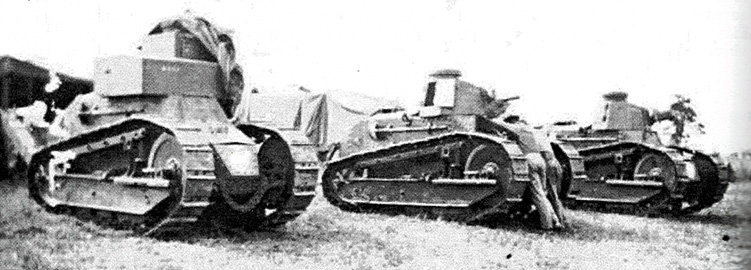

The year was 1922, four years after the end of the First World War, when more than 5,000 Marines—including the entire Fifth and Sixth Corps—along with their artillery, antiaircraft guns, M1919 tanks, dive and torpedo bombers, scout planes, and observation balloons descended upon Gettysburg—following their week-long, more than 80-mile trek from Quantico, Virginia, to the historic Civil War battlefield of 1863—for their annual summer maneuvers.

The troops left Quantico on June 19, arriving in Gettysburg on June 26. Some of the supplies and equipage were flown in or sent by railroad. It was said that it took the column more than a half hour to pass any given point along the line of the march.

The planned activities were two-fold: to train the troops and to hold public reenactments to promote the Marine Corps in the eyes of the public. The Marines held their public reenactments (specifically reenacting Pickett’s Charge, the game-changer that, on July 3, 1863, concluded the Battle of Gettysburg) on July 1, 3, and 4. The July 1 and July 3 reenactments were held in Civil War fashion, in conformity with the actual charge that occurred.

But the July 4 reenactment was another thing, altogether, because that day’s version of Picket’s Charge would be fought with all of the fire and fury and equipage of a World War I battle.

“On July 4, the Marines will fight the Battle of Gettysburg as they think it ought to have been fought… with tanks, airplanes, observation balloons and machine guns. They don’t need any rehearsal for this. They learned a good deal about it in France.” The (Baltimore) Sun, June 28, 1922.

Prior to the July 4 battle, the Marines announced that Colonel Frederick L. Bradman would be portraying Confederate General Robert E. Lee, while Major H.B. Pratt would portray Confederate General James Longstreet, and Confederate General George Picket was portrayed by Colonel James K. Tracey. Apparently, no one was assigned to represent the Union command.

Among the multitude of civilians that had arrived to see the battle was Colonel E.B. Cope, superintendent of the Gettysburg National Military Park, who had actually been attached to Union General Meade’s headquarters at Gettysburg during the July 3, 1863, charge. A number of Veterans of the war were also present to view the reenactment.

The Marines divided up their numbers to create the Union and Confederate forces needed to fight that battle.

Preparing for battle, the Confederate Marines were able to use their current uniforms by modifying how such was worn, including refiguring the slouch and floppy hats to the appropriate style. Beets were boiled to be used as blood during the battle.

The battle opened on July 4, with an artillery fire and the lofting of a Confederate observation balloon, which immediately triggered a dogfight between Union and Confederate bi-wing aircraft, the highlight of which was the shooting down of the observation balloon, which fell, burning the ground. The pilot threw out a dummy and, shortly after, parachuted himself out of the burning assemblage. The burning balloon landed somewhere on the west side of Seminary Ridge.

Around 10:30 a.m., smoke candles were lit ahead of the massed Confederate infantry to simulate the fog of war that would have been generated by all the mystery and artillery fire of July 3, 1863. Then came the Confederate advance, but unlike the deployment of Southern troops during the actual charge, in which the troops would have advanced in long shoulder-to-shoulder lines, they advanced in Squads and platoons as they would have done in battle in 1922.

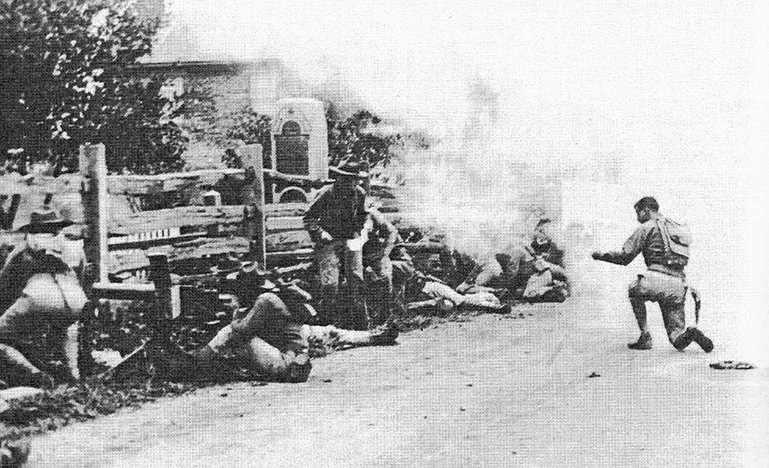

The Marines advanced onto Emmitsburg Road, where they deployed machine gun crews and their weapons units, supported by squads of infantry. The (Baltimore) Sun wrote on July 5, “The audience heard only the thunder of artillery and the tat-tat-tat of machine gun and the crack of rifles… while the visible infantry appeared and disappeared within the voluminous amount of smoke.”

As the Marines prepared to advance on what today is referred to as the High Water Mark (which marks the furthest Confederate troops advanced on the July 3, 1863, charge), Confederate dive bombers strafed the Union troops posted behind the stone wall that further denotes the High Water Mark.

Then came the tanks, which The (Baltimore) Sun described as seeming, “Like lazy animals, already gorged with battle and bored with the slaughter, they wobbled through the oat fields, converging on the Codori House, and at a few hundred yards began spitting flame and smoke from their one-pounders.”

Union troops were offering serious resistance in the Codori House and outbuildings, so the Marines ordered up two tanks to take them out. Another two tanks were deployed on the left flank of the Confederate advance. One of the tanks rolled up to the Codori House and fired a smoke round into the house through a window and the Union resistance ceased.

The rifles used in the battle fired blanks, but blanks had not been developed at the time for machine guns, so the machine guns were firing live rounds. Berms had been created a short distance around the Codori Farm, into which the machine gunners directed their fire. The tank more than likely only fired smoke rounds, as well as their machine guns. Every so many Confederate Marines carried shotguns with smoke shells that they would fire into the ground as they progressed to simulate artillery shell impacts.

The Union troops had also created several mock pillboxes between Emmitsburg Road and the High Water Mark, in which they placed their machine guns—probably firing also into the temporary berms—and these were soon silenced by the tanks.

The battle was also monitored by judges, delegating points for gains made or losses taken. When the Confederate Marines cleared all of the Union resistance from Emmitsburg up to the High Water Mark, the battle was called off, and the Confederate Marines were judged to have been the victors. The South had just effectively won the Battle of Gettysburg.

The (Baltimore) Sun wrote, July 5, 1922, “Cemetery Ridge fell today, the blazing hills and knolls that hurled back the Confederate Army’s massed attacks in 1863 were silenced this morning by the United States Marines. Attacking like Indians among the wheat shocks and through the stubble and oat fields, while big guns pounded to pulp and machine guns peppered to death the fortresses that had held the old Union Army safe 59 years ago.”

The Marines left Gettysburg on July 6 and marched back to Quantico. They would not engage a Civil War enemy again until their summer maneuvers in 1923, when they advanced on the New Market Battlefield in Virginia, only this time as Union troops!

Source: Last to Fall, Fulton/Rada

Three of four “Confederate” tanks await the battle.

Source: Last to Fall, Fulton/Rada

“Confederate” Marine setting up machine guns on Emmitsburg Road.

Source: Last to Fall, Fulton/Rada

“Confederate” Marine platoons assault the Codori House.