How the Breakup of a Continent Helped Prevent the Breakup of a Country

Richard D. L. Fulton

The Battle of Gettysburg, which resulted in an important stalemate between Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Union General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac on July 1 through July 3, 1863, prevented the advance of the Confederate Army through Pennsylvania.

Had the Army of Northern Virginia defeated the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, the Confederates could have advanced onto a number of Pennsylvania and Maryland cities, and even Washington, D.C.

Essentially, much of the outcome of the battle was settled some 175 million years ago, and further forged by tens of millions of years of weathering, which further sculpted the primordial Gettysburg landscape into the killing fields of 1863.

The real battle, as such, began during the Jurassic Period, as the North American continent was ripped apart—in geologic slow motion—of its African counterpart during a geologic phenomenon known as continental drift. It was during this cataclysmic event that also gave birth to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Jurassic Period was the central period of time some refer to as being the Age of the Dinosaurs, but the Jurassic Period was also marked as having been a period of cataclysmic geological events—massive earthquakes and the building up of massive magma chambers, comprised of molten rock and minerals—beneath the earth.

As the North American plate and the African plate drifted further apart, the fire and fury of geological rage was tempered as the distance between the two departed continents drifted further apart. Massive earthquakes petered out, and magma chambers that remained concealed beneath the surface hardened into a rock type known as diabase.

Much of the region at the time that the magma chambers had formed was covered with thick beds of red shale and sandstone that had been laid down as mud during the previous period (Late Triassic). The magma chambers penetrated the lower shale and sandstone layers of the Late Triassic but did not pierce completely through them to reach the surface. If the magma had broken through, they would have developed into surficial volcanoes.

Thus trapped, the magma slowly hardened into diabase, a rock type more weathering resistant than either the overlying shale or sandstone. As a result, over millions of years, the beds of shale and sandstone were weathered down, exposing the more resistant diabase.

The end result was that the hills and ridges of Gettysburg were formed by the tough diabase, and the ground level and lower elevations remained in the hands of the Late Triassic rocks (dubbed the Triassic basins).

So how did this impact the Battle of Gettysburg?

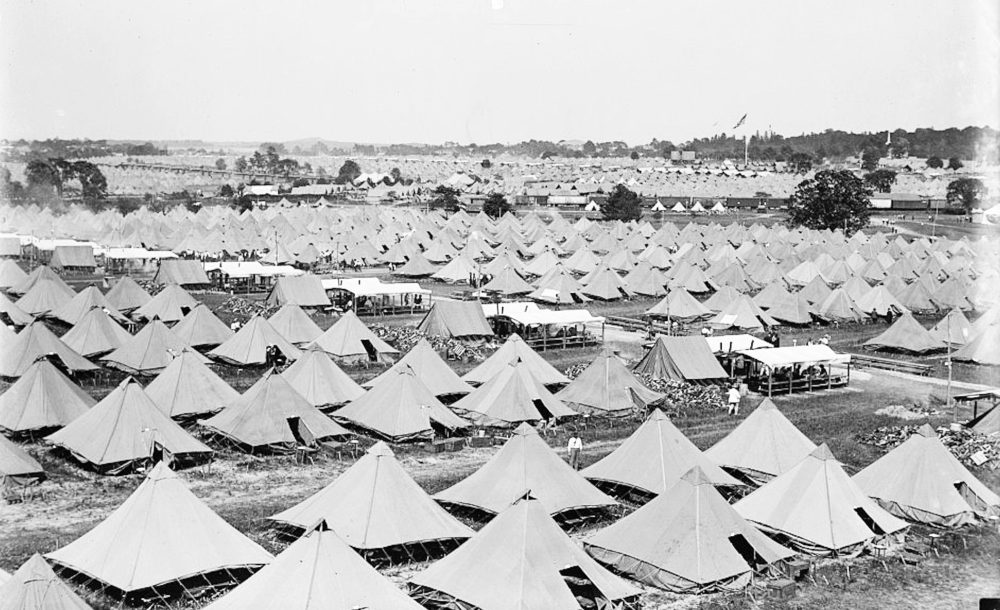

In the 19th Century (and before), most battles were fought for the main purpose of seizing the high ground (in the case of Gettysburg, the diabase hills and ridges). Not only did the high ground offer an advantage of observing enemy troop movements, but also afforded more defensive positions than if the armies had tried to defend themselves on lower ground (the shale valleys and flatter areas of Gettysburg).

During the Battle of Gettysburg, typical “high ground” features that were composed of diabase included the Devil’s Den, Big and Little Round Tops, Cemetery Ridge (which included the “High Water Mark” of Pickett’s Charge), Cemetery Hill, Seminary Ridge, Culps Hill, etcetera.

Much of the three-day battle pivoted on the effort to retain or capture these key positions. In fact, the epic climax of the battle was when the Confederate Army tried to drive the Union defenders off the Cemetery Ridge by marching three-quarters of a mile across a Triassic basin to assault the diabase ridge defended by the Union forces.

The Confederate forces had attempted the previous day to strike at the flanks of Cemetery Ridge, Culp’s Hill, and Little Round Top—both diabase and both attacked from Triassic basin formations—and both failed.

The 175-million-year-old magma chambers—created by the break up of a continent—proved resistant to time, and resistant to capture in 1863, and prevented that battle from being the one that might have assured the breakup of the country.

Courtesy of the Gettysburg NPS

View of the Triassic basin from the diabase hill known as Little Round Top.

“The Angle,” the farthermost point at which the Confederates penetrated the diabase ridge called Cemetery.

As the Confederate Army retreated from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863, they encountered Union troops in the area of Blue Ridge Summit. A two-day battle ensued in the middle of a thunderstorm that eventually spilled over the Mason-Dixon Line into Maryland.

As the Confederate Army retreated from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863, they encountered Union troops in the area of Blue Ridge Summit. A two-day battle ensued in the middle of a thunderstorm that eventually spilled over the Mason-Dixon Line into Maryland.