Richard D. L. Fulton

For three days, from July 1 through July 4, 1863, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, under the command of General Robert E. Lee, engaged the Union Army of the Potomac, under the command of General George Meade, in and around the Borough of Gettysburg.

On July 3, General Lee ordered a massed assault on the center, which failed to break the Union line, and thereby ended Lee’s campaign of marching his army across Pennsylvania.

However, in spite of the carnage, one single death struck the hearts and souls of Americans across states and territories: the death of a 20-year-old female Gettysburg resident who had been caught in a crossfire in a home located in the heart of what had become a “no man’s land” on July 3.

WHO was Mary Virginia “Jennie” Wade?

Wade was born in Gettysburg on May 21, 1843 to parents James Wade and Mary Anne Filby Wade, and was raised in Gettysburg. She had two sisters, Georgeanna Anna Wade McClellan and Martha Margaret Wade, as well as three brothers, Harry M. Wade, Samuel Swan Wade, and John James Wade. Martha Margaret Wade passed away after having only lived for four months.

WHAT propelled her into being regarded as a national heroine?

Jennie Wade became the only civilian killed during the bloody Battle of Gettysburg. This was fostered by the claim that she was killed while baking bread for Union soldiers during the battle.

WHERE was Jennie Wade killed?

On July 2, the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, the Confederate Army had pushed the Union troops from west of town into and through the Borough of Gettysburg and the heights that run from Culps Hill to the Rounds Tops, where the Union troops assumed a defensive “last stand” position.

Wade and her mother decided to take shelter in the home of Jennie’s sister, Georgeanna, who lived on the north side of two two-story apartments that had been created out of a house located at 548 Baltimore Street, just a short distance north of East Cemetery Hill. Jennie and her mother also felt they could assist Georgeanna with her newborn baby (Lewis Kenneth McClellan) to whom she had just given birth only a few days earlier. Georgeanna was also alone, as her husband, John Louis McClellan, was off serving in the Union Army.

Also sheltering in the home at the same time was brother Harry M. Wade and Ike Brinkerhof (of unknown affiliation).

WHEN was Jennie Wade Killed?

It probably had become obvious by the morning of July 3 that the occupants of the house were now in a “no man’s land” that had erupted between Union-occupied East Cemetery Hill and Confederate troops trying to advance up both sides of Baltimore Street towards the Union position.

Although the house had been pelted with bullets and even had an artillery round penetrate the roof (without detonating), the group decided to remain in place within the home.

It was reported that Union snipers were posted on the second floor of the house to contest the advance of Confederates working their way up both sides of Baltimore Street.

Jennie Wade woke up early, around 8:30 a.m. on July 3 and had left the house for water and firewood. She then returned to the house and began kneading dough to make the bread, when she was struck and killed by a bullet.

HOW was Jennie Wade killed?

According to “history,” Wade was struck and killed by a bullet fired by a Confederate that penetrated two doors (the kitchen door and the bedroom door) sometime after she had returned from fetching water and firewood.

However, since the house was basically located in a crossfire, one would have to had examined the fatal bullet in order to determine its source.

WHY was Jennie Wade killed?

It should be pointed out here that Confederate soldiers had previously tried to convince the family to leave, but they chose to remain. Clearly, a fight was going to unfold as Union troops dug in on East Cemetery Hill to defend the right center of the Union line as Confederates attempted to advance and potentially capture the position.

It seems quite probable that soldiers might have mistaken the figures inside the house as enemy combatants, since it would not have made much sense to them that civilians had remained in the house after all that had been, and was still, transpiring around it.

As the fight subsided, Union soldiers, probably the sharpshooters that had been posted, removed her body to the basement via knocking a hole through the second-floor wall, carrying her body into the neighboring apartment and down to the neighbor’s side of the home into their basement, where her body remained until after the battle when she was buried in her sister’s garden.

A Confederate officer had been killed on the front porch of the McClellan side, and his fellow soldiers subsequently attempted to bring up a casket to carry the body off in, but Union fire forced them to abandon the effort. After the fighting had ceased, the casket was salvaged and was used for Wade’s burial.

So, that’s the story… but is it the real story?

The problem is, the physical evidence does not support how she was killed, and circumstantial evidence does seem to question whether someone from the North or South had killed her. And, then there was the sudden change of a “death by friendly fire” to “death by enemy fire” that took place when her mother applied for a pension, which could not be paid unless the death was deemed due to enemy fire.

Problematic issues began with the two doors, through which the fatal bullet was alleged to have traveled, especially based on the “bullet hole” in the front door. Forget examining the front door. Photos taken over the decades, beginning soon after the war, reveal that the door was replaced three or more times with another door, and that the original door had four panes of glass (two over two) in the upper portion of the door.

It has been stated that the fatal bullet came from the Confederate-occupied, west side of Baltimore Pike, but the angle would not be right from any location on the west side to strike the door and penetrate it, along with penetrating a second door, to hit anyone in the house.

It has also been suggested that the fatal shot came from the Confederate-occupied Tannery on the east side of Baltimore Street, except that there were intervening houses located between the Tannery and the McClellan house.

The only thing the period media accounts disagreed on (they all agreed it was friendly fire) was if the fatal shot went through the door or a window. Knowing that the front door had glass windowpanes at the time, they both could have been right. Although, for the bullets to have been fired through the upper door window at an angle to kill someone inside means that the shooter had to be on a second-floor side porch of the house adjacent to the McClellan house on the same side of the street.

Another account stated that Wade was struck by the same “volley” of bullets that killed the Confederate officer on the front porch of the McClellan house. This points to Wade having been killed by Union gunfire.

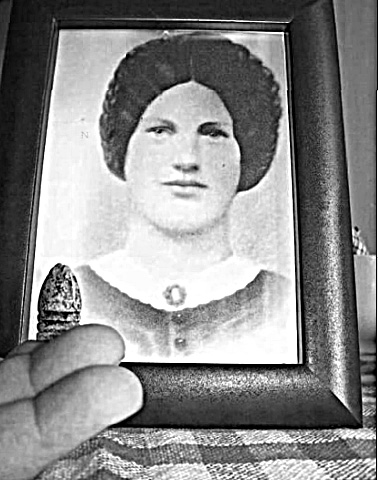

There is one final tidbit that appeared in 2007, in the form of a small package sent to the late Kenneth Rohrbaugh, then manager of the Jennie Wade House and Museum. The small package contained a bullet that had been kept by a Union soldier, found within the casket containing Wade’s body when it was being examined, before being removed to the Evergreen Cemetery.

As it turned out, the soldier himself had not removed the bullet. It was actually a family member who had examined the body (preparatory to presenting his findings before Congress) who found the loose bullet.

The author of this article—a former Civil War relic dealer—was asked by Rohrbaugh to examine the bullet and identify it. It was a .577 caliber Union Minie’ ball that had lost its velocity, but still had enough force that the imprint of Wade’s muslin-clothing was still embedded in its nose.

Not only had the bullet established the source of the gunfire but had also established that Wade had been struck by two bullets, one spent round and the fatal one.

The tell-tale bullet, one of two that struck Jennie Wade. (Photo by and from the personal collection of R.D.L. Fulton. Initially published in The Gettysburg Times, August 11, 2007)

A 1904 view of the McClellan side of the home where Wade was killed.

Note the four glass panes at the top of the door.