How I Came to Know My Father ~ Part 2

by Sally T. Grove

Using Her Father Chester L. Grove, Jr.’s Diary and Reflecting on What He Had Written

I was 20 years old when I first came to understand my father. He invited me to return home to live with him on Thanksgiving Day 1977 as a way to relieve the financial pressures I faced as a newly graduated college student. It was then that I found a small stenographer’s notebook in a trunk in the basement. As I read through it, I learned about a part of my father’s life during World War II that he, like many Veterans of that war, didn’t share easily.

“January 11th, we left the good old Terra Firma of the U.S.A. for Europe … January 21, 1945, we landed at Le Havre, France… We had a cold reception on landing. The temperature was below zero… We rode 60 miles in open trucks to Camp Lucky Strike, the coldest ride of my life. We arrived at camp at 2 a.m. frozen stiff. Our night was far from over yet, as we had to pitch tents in the snow and, when we finally did get to bed, we were too cold to sleep.”

I took U.S. History in high school, and I guess I should have known Dad fought in WWII. Still, Dad never talked about the war.

“The camp of former German airfields with a large concrete runway was infested with mines and booby traps. We trained in snow and then knee-deep mud for about a month, making very hard marches. During that time, my feet were frozen so badly that I couldn’t wear shoes for several days.”

Studying history is nothing like reading a journal from WWII. They didn’t talk about the cold and the suffering in our textbook—feet frozen so badly that you couldn’t wear shoes! Thankfully, that is a cold that I have never known.

“On March 25th, we moved up to the west bank of the Rhine. We arrived at 8 p.m., ate, and at 10:30 p.m. with but two hours’ sleep, we started our assault crossing. For hours, our artillery had been hammering the east bank and now the forest was a blazing inferno. Our company crept down the twisting trail to the river’s edge. As we reached the riverbank, we were fired upon by a hail of machine guns and 20 mms, which pinned us to the ground for half an hour. The railroad station to our front was ablaze as a result of the firing… The second platoon tried to launch several boats but was mowed down before they could load them. Finally in desperation, Captain Brown asked for a boat load of volunteers to try to make it across… our whole squad stepped forward…”

Dad was a part of the assault on the Rhine! We learned so little about WWII in my high school history class. We learned almost nothing about the Holocaust or how the United States declared neutrality at the start of World War II in Europe. We did learn about troop movements, and my limited memory tells me that the assault on the Rhine was a big deal. It precipitated the beginning of the end.

“… we got out only about thirty yards before they spotted our boat. Everything broke loose at us but we kept going… halfway across and by this time about two blocks down stream, we again received heavy fire but again paddled through it. Finally we were about 40 yards from the Jerry side, right opposite a high wall on which the machine guns were mounted… this time the jug-heads had our range and were peppering the boats so we decided to swim for it. Stripping off all equipment but our guns, we dove overboard…I was in mid-air when I felt a hot sear in my shoulder…I found that I could not use my left arm, but I managed to swim with one arm to shore…I was the only one of the seven in our boat that was hit…as we hit the sandy beach, they resumed firing on us and the engineer in the boat with us was hit and fell at the water’s edge. The rest of us took cover at the base of a wall about 25 to 30 feet high.”

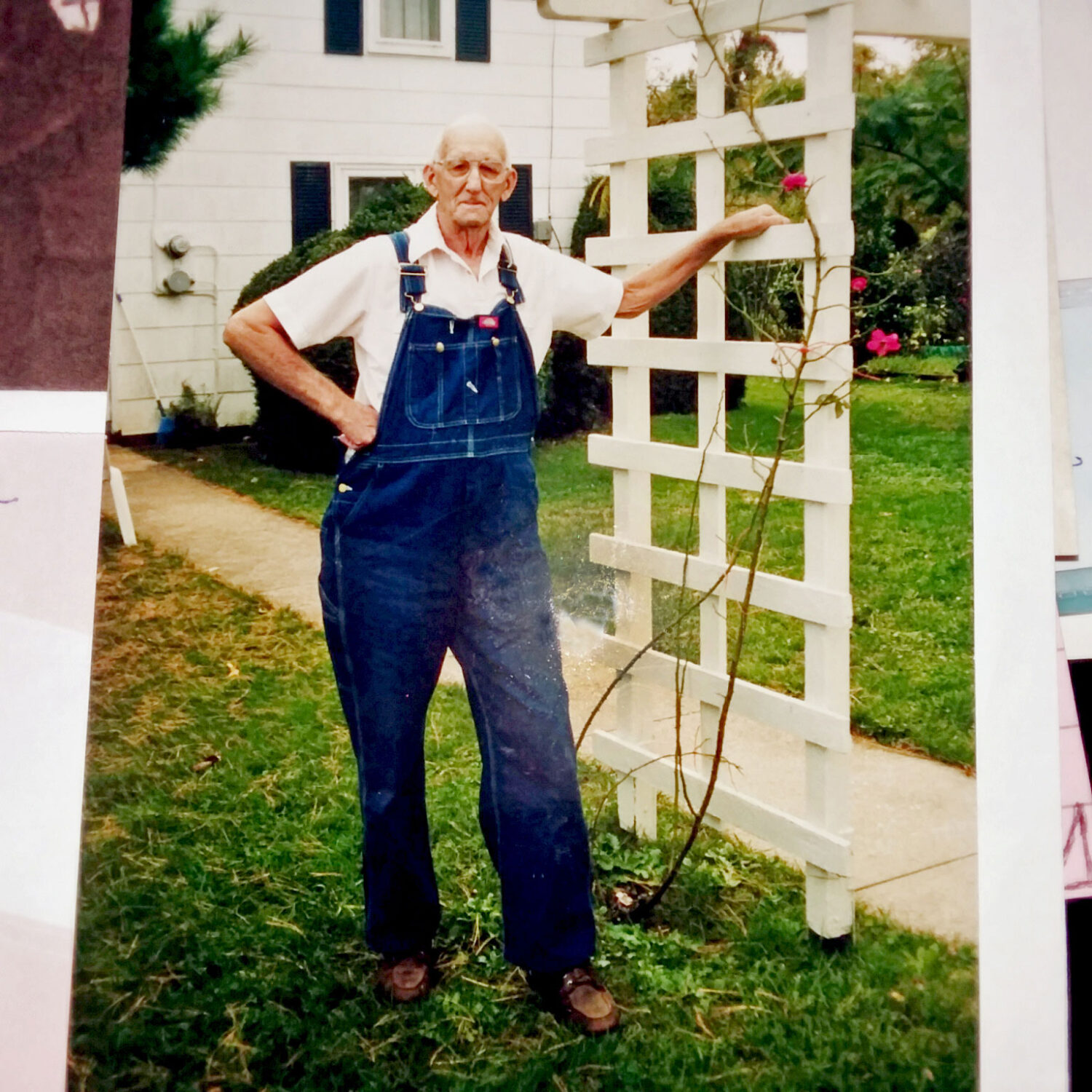

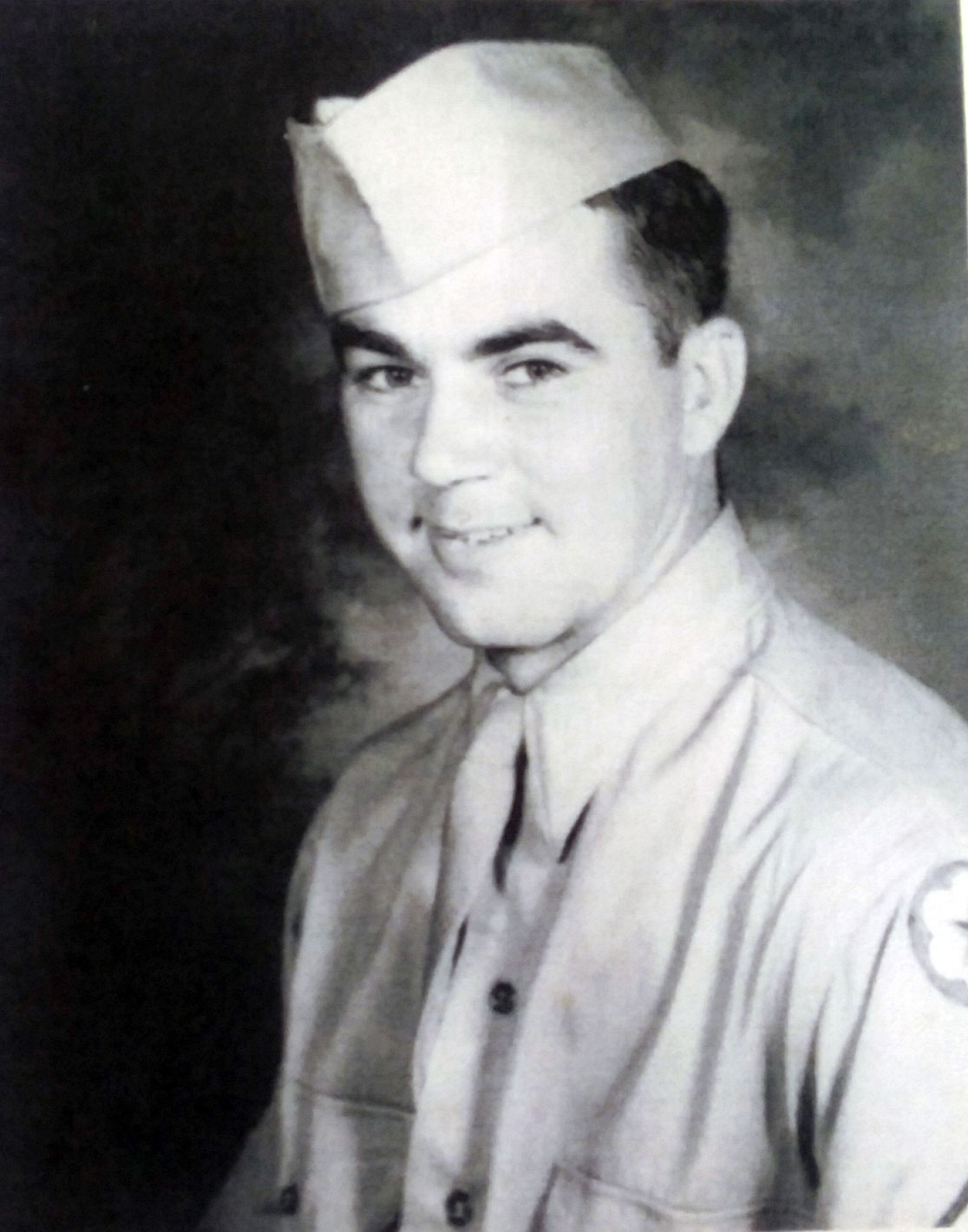

I have seen that scar on Dad’s shoulder since I was a kid. The scar is as much a part of Dad as the dimple on his chin or his chipped front tooth. I knew his tooth broke during a childhood flight over the handlebars of his bike, and Mom always said Dad’s dimples made him look like Robert Mitchum, a movie star from their generation. But the scar on his shoulder—I had not known the event that had caused it.

“The engineer was in terrible agony and laid groaning and praying in a blood-chilling voice. We could not go to his aid as the Jerry’s kept showering the area with lead. A little later, however, we crept over to him, but it was too late. A bullet had hit his spine and he was dead.”

My father saw a friend die. I cannot imagine my father enduring such a tragic loss. Did a soldier’s training prepare them to go on when they had lost a friend?

“… We made our way back to the safety of the wall, as shells were hitting directly out from us in the water about 20 yards away. We were pinned between two lines of fire, one from the Jerry’s and one from US troops.”

This sounds like a scene from an old war movie…

“Pain seared my body. I don’t know why but one of my first impulses was to spit to see if my lung was hit, which I guess it was not, as I did not spit blood. I could see the bullet holes in my jacket right at the point where the sleeve and shoulder seam is, but could not find where the bullet left, although my chest at the heart area was very sore and full of blood as well as swollen. My whole shirt was blood-soaked and I feared I might bleed to death although the blood did not now seem to be running from the wound. We lay very still along the wall, the hob-nailed boots of the Jerries sounded just above the wall and we could hear them loading their machine guns and talking in low voices. My arm was stiff and throbbing now like an engine.”

This wasn’t an old John Wayne war movie. This battle was real, and my dad was the main character. How frightening it must have been for him, bleeding and in pain, waiting, not knowing what would happen next. The design of his future was out of his hands.

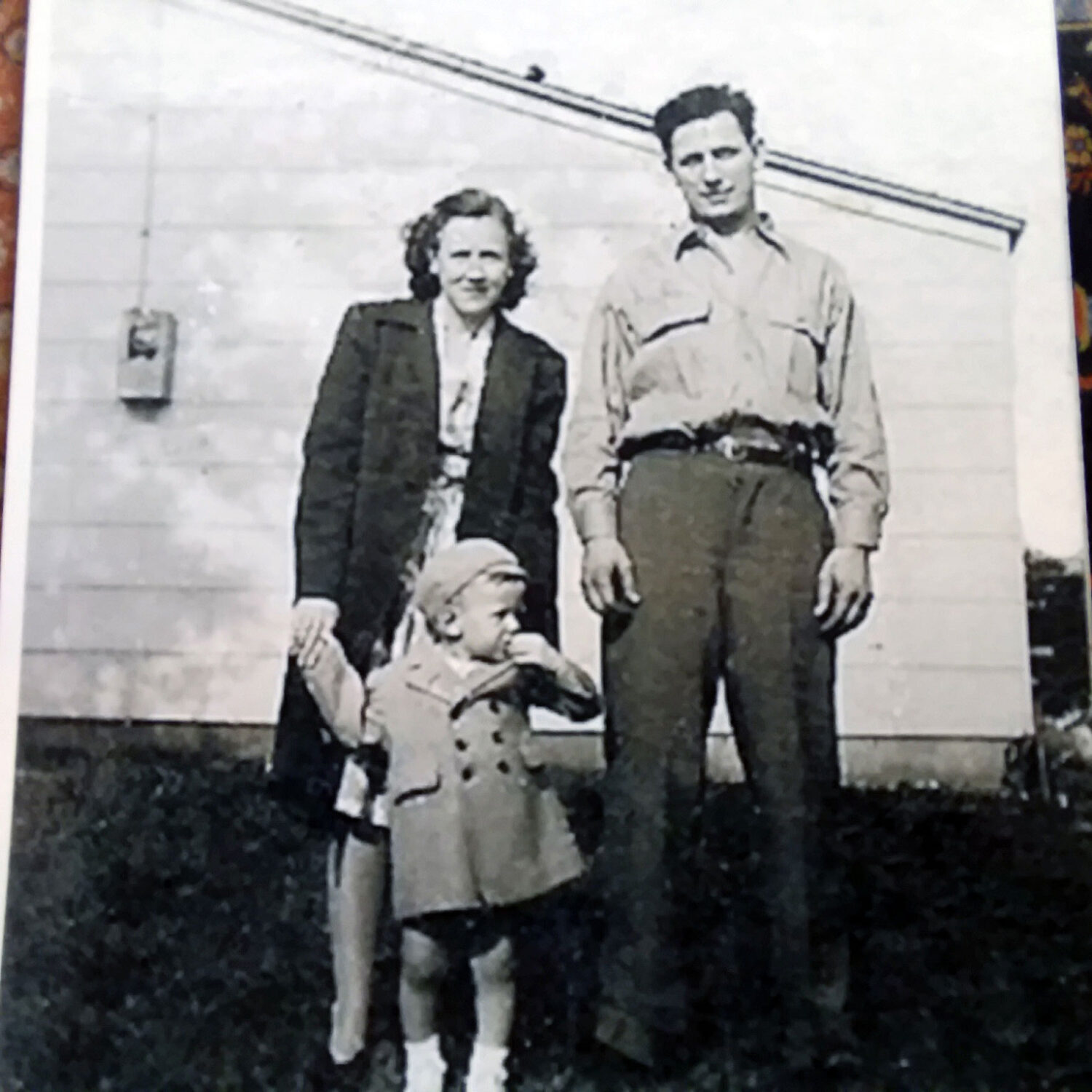

Sally Grove pictured with her father and mother in 1972.

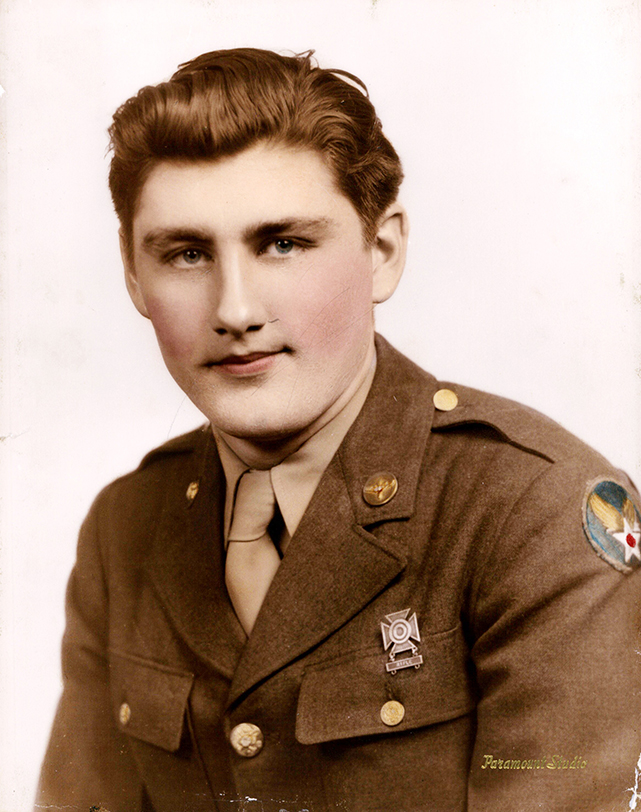

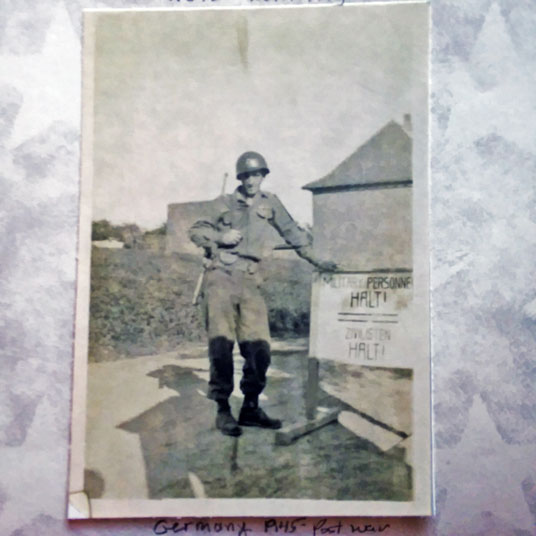

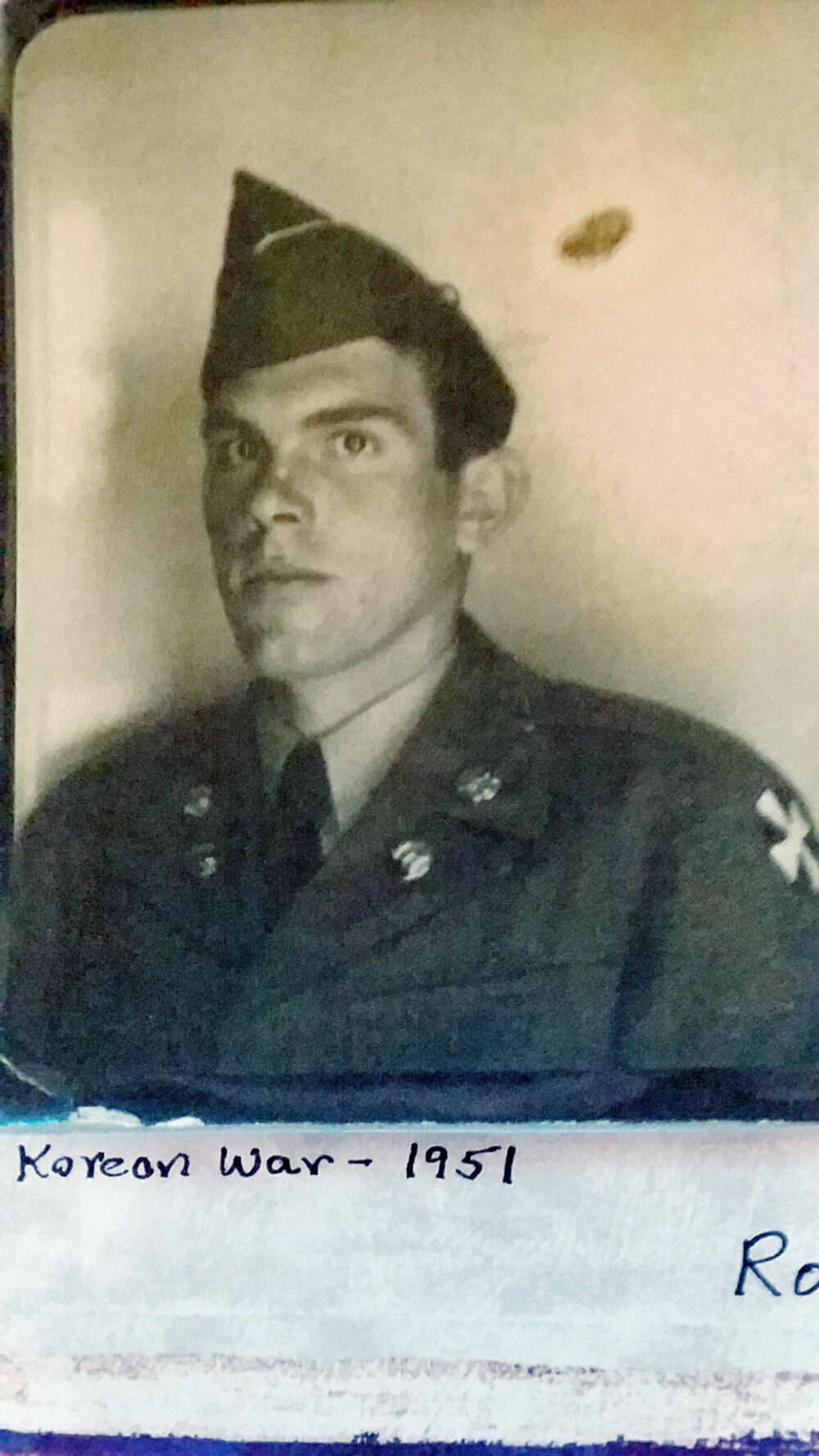

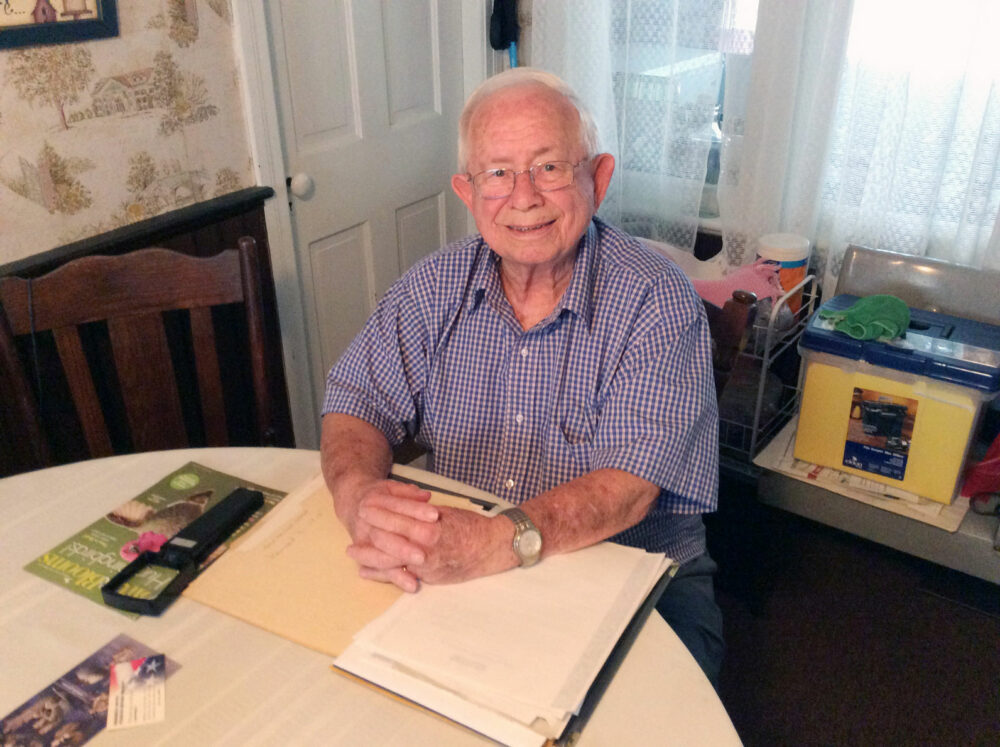

Courtesy Photo of Chester L. Grove, Jr. in Uniform