by Priscilla Rall

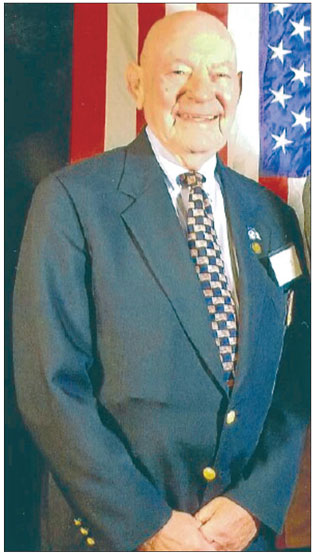

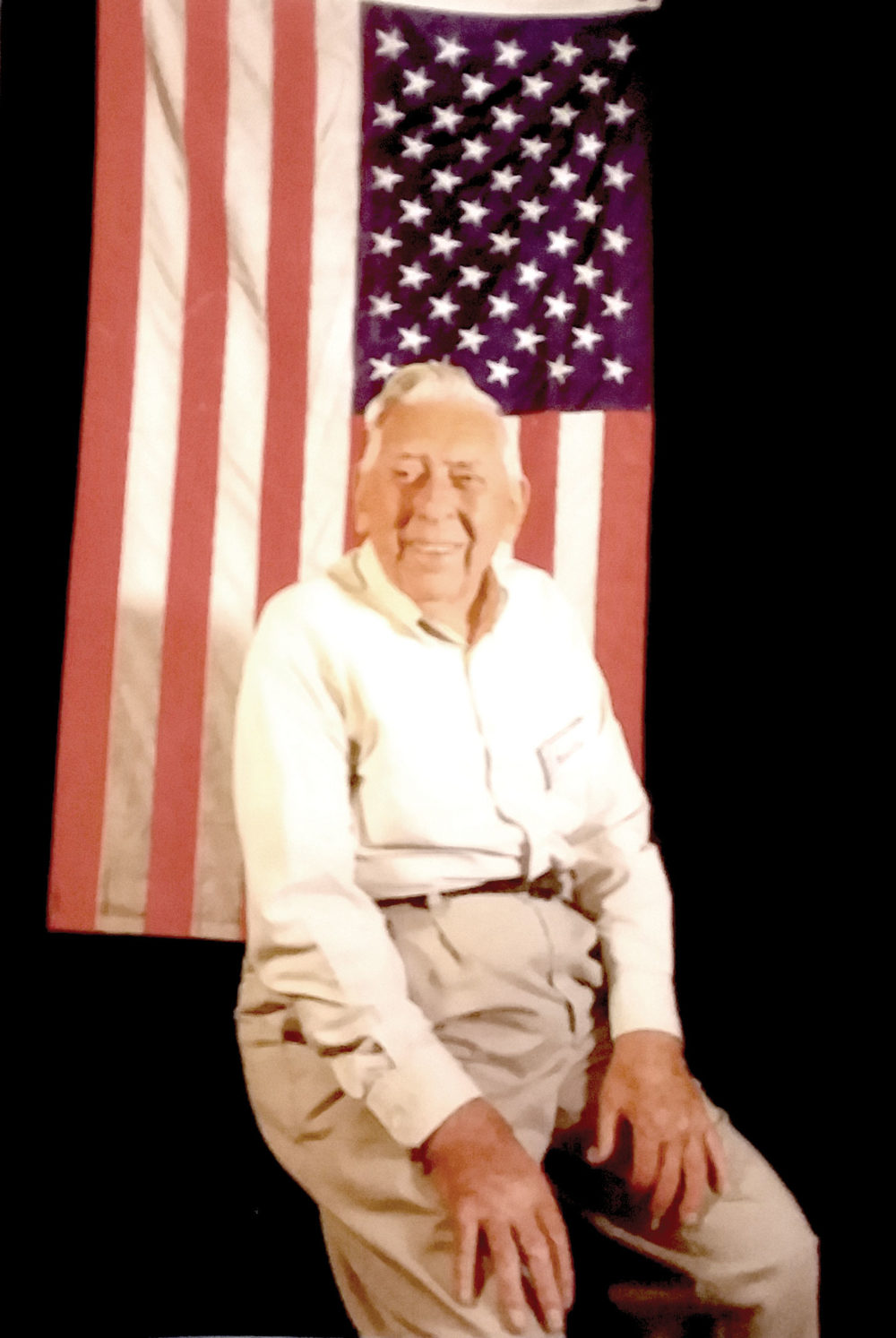

Sniper Wings Seiss

The Seiss family had settled in the Frederick area in the mid-1700s. Born in 1925 in Graceham, Sterling Seiss was a descendant of these first settlers. The family home, where he now lives, was built in 1825, near what is thought to be an ancient Native American trail. Sterling found many arrowheads in the fields by the house. The original stone spring house near the old home still stands. Sterling had six brothers and six sisters, and he remembers that his grandmother kept butter and milk cool in the spring house. When the kids were sent to get milk from there, they were allowed to bring up one bottle of homemade root beer that was also stored there.

Sterling’s father worked as a barn builder for Ralph Miller, and also farmed. The children were kept busy with daily chores. Sterling gathered kindling and eggs, while his older brother filled the wood box. The other boys cared for the horses, Prince and Bob, as his father never owned a tractor. For Christmas, the Seiss children got hard candy, oranges, and sometimes a new pair of socks. They enjoyed the many church festivals nearby. Family was everything to the Seisses. Their cousin, Russell, had lost his mother at an early age and he often stayed with the Sterling family; it was not unusual for the children to stay with aunts and uncles or grandparents for a time.

Sterling left school after seventh grade and worked for a time at the Gem Laundry in Frederick, helping to pick up and then deliver the cleaned clothes. At this time, he lived with his brother in Frederick and earned $6.00 a week. When the laundry closed, he rode his bicycle back to Thurmont, where his parents were living. At that time, Thurmont was quite a hopping town, with a movie theater that charged 17 cents a ticket. Even Graceham had a store, a warehouse, a post office, and, of course, the Moravian Church.

However, as the Depression loomed over the country, it affected the Seiss Famly. They lost all of their savings when the Central Trust bank folded and, consequently, lost their farm. Sterling’s father took any job he could find, and they moved from one rented farm to another. Sterling remembers hobos who rode the rails and would split wood for a meal. At one point, Sterling worked for John Zimmer on his nearby farm. He also helped deliver milk on a horse-drawn wagon.

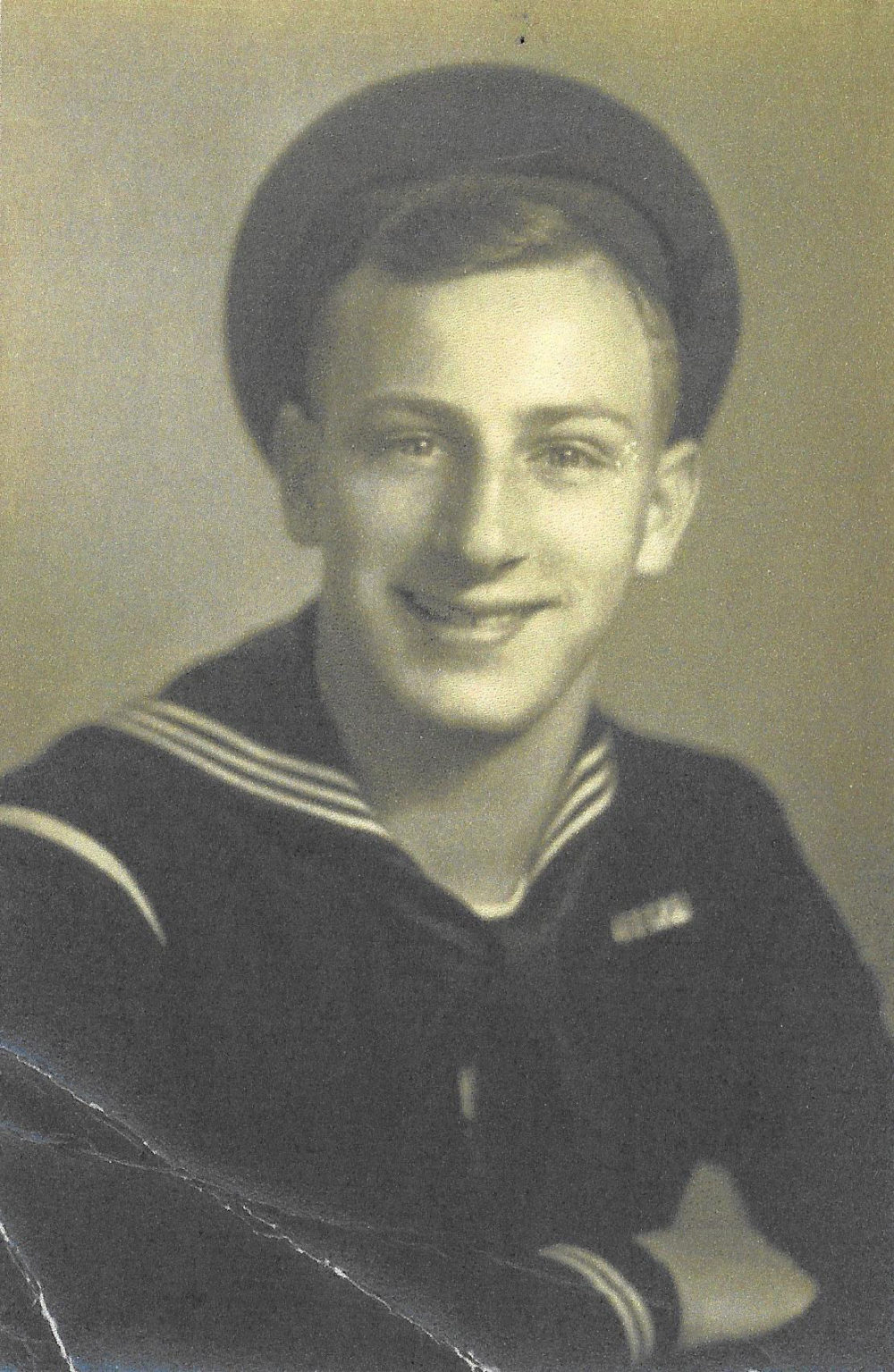

When he turned 18, although he could have asked for a farming deferment, he decided to join the Army. He was inducted in January 1944, and after training, he shipped out to New Guinea. There, with Company F in the 34th Infantry, they searched for any Japanese still remaining in a “mopping up” operation. They were warned to beware of snakes and “head hunters.” Sterling recalls thinking “that doesn’t sound very good to me!” Thankfully, they found no enemy soldiers, snakes, or head hunters. Then they sailed off for the Philippine Islands, landing in Leyte, where again they were in a “mopping up” operation.

On December 11, 1944, as the company was digging in for the night, Pvt. Seiss felt a stinging sensation in his left shoulder. When his buddy called for a medic, the captain quickly came; stripping off Seiss’ jacket, he found a bullet hole through his shoulder and a burn mark made by the enemy sniper’s bullet across his back. He was ordered to report to the field hospital, but he had no idea where it was! Just then, a young Philippino boy spoke up, “Me know.” So, Sterling left his company and reported to the field hospital, where the doctor told him that he was going back to the states. The doctor told Sterling how lucky he was—an inch lower or an inch higher and he would be dead. After his recovery in Georgia and then at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, he was discharged in May 1946, with a Good Conduct Medal and Purple Heart.

Sterling had always loved working with animals, so it is no surprise that for the rest of his life he was involved in farming. He had a brief first marriage that produced a son. He then married the love of his life, Mary Jean Harbaugh, in 1952. Together, they had three children, and farmed, raising heifers and pigs. Finally, in 1972, he was able to buy the home place where he lives to this day.

In the 1980s, I was one of many who bought piggies from Sterling, and I remember seeing him in his red pickup filled with crates of outdated milk he got from local dairies to feed his hogs. Sterling Seiss is one of the dwindling number of the “Greatest Generation,” to whom our country owes a great debt.

This quiet hero survived a Japanese sniper to return to his beloved Frederick County, where he lives out the last of his life in anonymity, few realizing the sacrifices he made in WWII.