Maryland’s Ancient Dogs

Richard D. L. Fulton

Long before humans traversed the plains and forests of Maryland, and millions of years before the Chesapeake Bay even existed, there were the “Bone Crushers.”

This Maryland version of The Land That Time Forgot occurred some 12 to 20 million years ago, when the Atlantic Ocean had made a major incursion into Maryland in the form of a large bay (referred to as the Salisbury Embayment). The shoreline of this bay, which stretched from west of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, rejoined the main oceanic shoreline in the Philadelphia area.

This was during a period of time referred to as the Miocene Epoch, when the Maryland waters were patrolled by 50- to 60-foot sharks in search of whatever they needed to kill in order to sustain their growth and size.

But “Bone Crusher” was not a shark. It was a dog (in fact two different species of dog), that were members of a group scientifically known as Borophaginae, which literally translates from Latin to “gluttonous eater.” Specifically, the two species of bone crushers that have been recovered from the Chesapeake Bay fossil deposits have been tentatively named Cynarctus marylandica and Cynarctus wangi.

In Maryland, only a few teeth of the Cynarctus have been recovered from the escarpments along the western shores of the Chesapeake, known as the Calvert Cliffs. While these cliffs are primarily clay, marl, and sand beds deposited in the oceanic Salisbury Embayment, occasionally, the remains of land animals are found whose teeth and bones had been washed into the ocean via rivers and streams in which proximity the animals had lived and died.

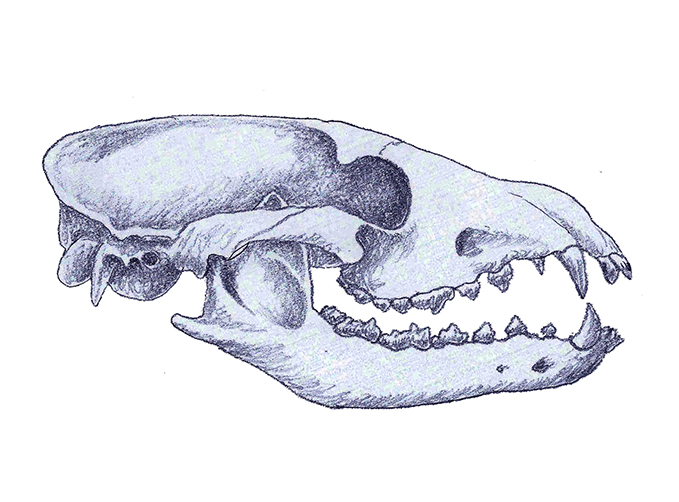

The Borophaginae, Cynarctus included, received the nickname “bone crusher” because the teeth of the animals were clearly adept at smashing the bones of their no-doubt sometimes sizeable prey—whether live-killed or scavenged—to smithereens, presumably to gain access to the marrow. Modern hyenas have similar teeth for crushing bones.

It has been generally held that climate change (during which period of time the climate was becoming more arid) taking place during the Early Miocene Epoch resulted in the reduction of lush vegetation, which in turn, resulted in the expansion of grasslands.

Because this change in habitats likely impacted the proliferation of plant-eating prey of the carnivores, the “fine art” of bone crushing evolved to allow these carnivores to extract more nutrients from each kill than that faced by carnivores of lusher times. Modern-day hyenas, who developed similar teeth, also live in an arid climate.

“In this respect, they are believed to have behaved in a similar way to hyenas today,” according to the primary author of a research paper discussing one of the new Cynarctus species, Steven E. Jasinski. Jasinski is a paleontologist and zoologist, employed by the Department of Environmental Science and Sustainability at Harrisburg University of Science and Technology.

Maryland’s bone-crushing Cynarctus were not big dogs, having apparently been about the size of a coyote. Also, researchers believe that Cynarctus may not have depended entirely on meat and bone-crushing for their diet, but may have also added insects and even plants to their diet, according to futurity.org. Futurity.org published a synopsis of the research paper, describing Cynarctus on their website, noting “Despite its strong jaws, the researchers believe C. wangi wouldn’t have been wholly reliant on meat to sustain itself.”

Some other attributes had been deduced from crushed bones and coprolites (excretion) found at fossil sites outside of Maryland, bearing traces of the Borophaginae. It may have been possible that Cynarctus was a social pack hunter (like modern-day wolves), and that bone-crushing served as a social activity for the pack.

In addition, coprolite pile clusters have been found in areas inhabited by Borophaginae, which would suggest they were left as territory markers, also according to a research paper published by multiple researchers, including Xiaoming Wang.

Cynarctus existed for about 5.7 million years, becoming extinct by the end of the Late-Miocene or the early stages of the period of time that followed.

Painting: An artist rendition of a member of the Borophaginae. Painted by Charles R. Knight, 1902, Public Domain.

Illustration of a Cynarctus Skull

Source: Wikimedia Commons