Submitted by Joan Bittner Fry

This article came from The Telephone News, VOL. VII, No.18, and was published by Bell Telephone Co. of Pennsylvania, The Delaware & Atlantic Telegraph & Telephone Co, The Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Co, The Diamond State Telephone Co, and The Central District and Printing Telegraph Co.

At that time, telephones were in their infancy. This publication gave information to employees of how to work together and how to share knowledge of their job with fellow employees, stating that “with our company there is no occasion for the ‘keep it under your hat’ habit.” This publication was for all employees, whether in the Plant Department or the Collection Department.

There were 16 pages with 30 photos throughout of the Blue Ridge Summit and Waynesboro areas, giving updates on underground cables and conduit installations in specific areas.

The Blue Ridge Mountains Resorts

Suppose—just suppose, remember—it is a hot Friday afternoon in late August. You, a humble telephone man, are sweltering in your office. You are almost all in. As you are about to give up the day’s work in despair, a friend drops in. He notes your wilted look. It is the psychological moment.

“What’re you going to do over Sunday?” he asks.

“Can’t imagine. Simmer, I reckon.”

“Never,” he shouts. “Get your grip and your golf sticks and come with me. You’re going to Blue Ridge Summit.”

Bang! Down comes the desk lid.

Blue Ridge Summit

Was there ever a clever combination of words? Blue—that’s plain enough. Even to the most unimaginative mind, it suggests its complement: skies. Ridge brings the picture of a green-treed mountain. Summit speaks of a high place, the top o’ the world, a place where breezes blow both day and night. “Blue Ridge Summit,” then, sounds well to you.

Let this be your introduction to “The Mountain.” You go. And what do you find?

Let us see:

High at the top of a giant ridge, just where Pennsylvania meets Maryland: where the air is pure, the water is crystal and the sky is azure; there, to locate it absolutely sans superlatives, there you find the Blue Ridge Mountains resorts.

There are a number of communities in the region; Monterey, Blue Ridge, Buena Vista, Pen Mar, and Blue Mountain are the most popular. Just a mile or two down the mountainside nestles the live little borough of Waynesboro—9,000 souls, and the heart of the vicinity.

And best of all, the region is only two hours away from Baltimore, three hours from Washington, and four or five from Philadelphia.

So, after a two-hour train ride, first through fertile valleys and farmlands, then up the gradual ascent of the mountains, you step from your Pullman into a cool, green bower through which the sun’s last rays are sloping. Your hat comes off instinctively. The breeze is playing tricks with your emotions and with your hair.

Blue Ridge Summit has come true. That first night you sleep the sleep of a man without a care. It is almost too good to be true. In the morning, shortly after “jocund day stands tiptoe the misty mountain tops” (Shakespeare), the horses are brought around. You mount and follow your guide down a broad, well-kept avenue. Automobiles are in evidence at intervals up here, but horses seem to have the call.

Probably the first thing that strikes your eye is the character of the “cottages that border you on the right (Monterey Lane). Each has its own perfect setting of flowers and greens. Comfort, convenience, and luxury speak from their every line, from the garage at the telephone loop entering the eave.

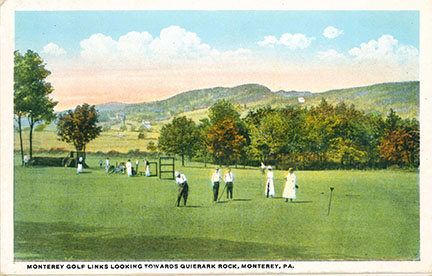

Presently, on the other side of this same avenue you approach a golf course, tennis courts, baseball grounds, and finally, a typical country cub house.

“The Monterey Country Club,” your friend explains as you canter past. For a moment, you are tempted to give up the ride and try out the fairway of the golf course that stretches out level before you, almost as far as the eye can reach. But your friend persuades you that it is better to postpone this pleasure until later—he has other things in mind for this morning.

Then comes a sharp turn to the right, a winding, easy climb, and step by step, you mount to the famous Monterey Terraces. As you ascend, each summer home seems to outdo its neighbor. At last you have reached the highest point of the terraces; you halt your horses for a moment, and your friend points to a mountain gap far across the checkerboard valley.

“Gettysburg Gap,” he says. “Look sharp near the mountain to the right, and you’ll see the spires and monuments of Gettysburg itself. Probably no other of the many views you may obtain will give you such a thrill as this very one. There, nearly 30 miles away, sparkle the granites and marbles of the historical battlefield. High above them, you can dimly see the towers of its churches and of Pennsylvania College, where perhaps, you have had friends, or it may be where you have attended school.

Twisting here and there throughout this particular neighborhood there is a strange looking grass-grown ditch that looks as if it might have been meant for a railroad cut at some ancient date. And that, it transpires, is exactly what it is. It is the remains of “The Old Tapeworm Line.” If this is going back a little too far for your memory of historical affairs, you will probably inquire further into the details of that interesting case and you will learn something like this:

The Tape Worm Line was an idea of Thaddeus Stevens, Pennsylvania’s “Grand Old Commoner.” About 1835, while he resided in Gettysburg, he conceived the idea of building a railroad to start at Gettysburg, run down through Franklin County and then turn south, tapping the richest parts of the southern counties wherever it was found advisable and convenient. Stevens, it should be remembered, had extensive interests in Franklin County. This probably accounts for the aggressive way in which he stood sponsor for his railroad proposition through many years of discouragement. The State finally granted him a large appropriation to take up the work. It was at the time of the great craze for internal improvement and development, and immediately upon receipt of sufficient money, the managers of the railroad began work all along the proposed line. They worked lustily, no doubt, and spent just as freely. Results followed rapidly; that is, negative results. Their funds were soon exhausted, the development boom collapsed, the State refused further aid, and operations ceased. History tells us that not a mile of the railroad was completed. The long, worm-like depressions in the vicinity of Monterey and Blue Ridge Summit certainly bear out the statement.

Mason and Dixon Line

A wide detour is now made. “I want to show you a little stone that has a rather interesting history,” says your guide. A sharp gallop and you come to the spot, dismount, and step probably half a dozen paces into the dense woods at the left of the road. Your friend turns sharply, places his hand on an upright wire cage about four feet high and points to the ancient looking stone within it.

“See that stone?” he asks. “This is a crown stone of the famous Mason and Dixon Line. The crown stones are placed at intervals of five miles; plain ones mark every intervening mile. On the southern side, you can dimly see Lord Baltimore’s coat of arms, and on the opposite side, the more familiar insignia of your own William Penn. I suppose I hardly need to explain their significance.

“This stone,” he continues, “is one of a great number shipped to this country from England about 1767 for the very purpose they now serve. They were unloaded somewhere along the Delaware line. Two young Englishmen by the name of Mason and Dixon then made the historic survey which later came to mark a commonly accepted boundary between north and south. Many of these stones had to be carried up the steep mountain paths on the backs of mules—one stone to two mules, securely strapped between them. At that time, they tell me each stone was at least four and a half feet out of ground. As you see, they are now within a few inches of the surface. Why? For the simple reason that lately they have become so interesting to visitors that everyone who came to see them considered it his or her duty to chip off a piece of the stone as a memento of the occasion.”

“Uncle Sam had to step in to prevent their total destruction, and a few years ago, he set about replacing the same old stones, and at the more exposed locations, he covered them with iron wire cages just like this one. A re-survey of the Mason-Dixon Line was also made about six or seven years ago. It was found almost absolutely correct. It runs through the heart of the Blue Ridge resort region. One of these stones stands a few hundred feet south of the Blue Ridge Summit Station; another can be found within a few feet of the Pen Mar Station. And that is the story of the little gray stone.”

Luncheon over, you naturally want to get back to that golf course, that is, if you’re a devotee of the sport. It is a corking little nine-hole course of something more than 2,000 yards. It is fairly well-filled with players, and as you take your stance, something tells you the wind in the air of this place is going to stretch out your every drive to its greatest and straightest length. As you follow your ball, you learn a little more of the Monterey Country Club. In the first place, it is kept up entirely by the cottagers and through private subscriptions and nominal dues. Any member or his guest has all the numerous pleasures and privileges of the club. It is modern in every respect. There is a well-appointed tea room for the ladies and every afternoon you will find a large representation of the colony seated there chatting and sipping their beverages, while they watch golfers or tennis players out in the open. Few mountain resorts can boast of such a well-managed institution.

It is Pen Mar in the evening, of course. Here is another interesting name for you. If I am not mistaken, half its charm comes from the fact that nine people out of ten discover its derivation for themselves. Pen from Pennsylvania, you see; and Mar from Maryland—meaning, of course, that the place is located partly in one state and partly in another. Assuredly, it means also that it is a spot where pleasure-lovers from both commonwealths convene. This park, you learn, was formally opened on the 31st of August just 33 years ago. The famous 5th Regimental Band of Baltimore officiated on that occasion. This year the anniversary of the date was recognized and celebrated in splendid style.

Pen Mar is becoming more of an all-year resort every season. At the present time, there are about 100 cottages, opened mostly by neighboring cities and from Waynesboro. The splendid order maintained in the vicinity has had a great deal to do with this steady growth. In the very beginning, Maryland legislature made a wise provision: that no intoxicating liquor could be sold within a certain distance of the park. Besides, it is well policed. Good order is insisted upon. At the dance pavilion, where you will hear the best of orchestra music from 11 A.M. to 11 P.M. daily, sons and daughters of the most respected and most prominent citizens for miles around safely gather. On special occasions, as many as 15,000 people visit the park in one day.

This completes your day, and a big day it was. You retire with the conviction that cities are good enough to work in, but that a mountain top is the one place to enjoy life.

The next day is Sunday according to our imaginary schedule, and in keeping with the day, you are glad to learn that the plans are to drive quietly over the sometimes steep but always well-kept mountain roads in the vicinity of Pen Mar and Buena Vista.

Buena Vista Springs has a mammoth hotel, a colony of cottages, and a reputation for entertaining distinguished guests. A great many Washington officials, including foreign ambassadors and their suites, have the Blue Ridge habit. It is rather remarkable to note that when they once spend a season at this resort, they usually come back for more. This year, the Japanese ambassador and his elaborately outfitted staff constitute the main attraction for the curious.

Near Pen Mar is the picturesque freak of nature known as the Devil’s Race Course. This is a long stretch of greenish rocks with absolutely no vegetation growing between or on them. At one time, it probably was the bed of a mountain stream. Now, by some strange phenomenon, the rocks are on the surface and the water is underneath. You can hear it rushing through its subterranean channels. Another feat of the race course, one not so pleasant to contemplate, is the fact that the rocks are infested with snakes of several kinds and all sizes, Rattlers, however, seem to be in the great majority.

As you climb on up the mountain you presently come to the observatory at High Rock. It is a three-story structure and rises about 40 feet above its rock foundation. They say it is necessary to anchor it to the rocks by massive bolts in order to preserve it during the gales that blow at this high point. It is about 2,000 feet above sea level. As you stand there looking, first into Pennsylvania and then into Maryland, you feel that it has been aptly named “the place of perpetual breezes.” Straight down below the observatory falls a precipice nearly 200 feet deep. About 1,000 feet below, the railroad winds its sinuous course down the mountain. The valley, broad and checkered, lies beyond. Your guide points out to you the steeples of Chambersburg, 24 miles away. Then, he turns and shows you the cluster of buildings that is Hagerstown, just about as far in the opposite direction. The blue peaks of the Appalachian Mountains skirt the horizon and form an entirely fitting background for the picture.

There is just one higher spot than this. It is known as Tip Top Tower, and is located on the summit of Mt. Quirauk, 2,500 feet above sea level. From this altitude, you can see, on a clear day, into 22 counties of the four states of Maryland and Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. The locality has special historic charms, for in the late war, the two opposing armies met time and again at one point or other within sight of Mt. Quirauk. Further back than that in the Revolutionary War, savages and Hessians, imported from across the sea, trod the same ground on which you now stand.

Monday morning you start down the mountain side to bustling Waynesboro. This town is the industrial center of all the surrounding country. As an indication that this is not mere flattery, let me tell you that in the borough of 9,000 inhabitants, there are about 900 telephone stations. The percentage of development will strike you at a glance as being rather exceptional in a community of this size.

Thus, your weekend comes to a close. You have enjoyed yourself, learned a number of things, and missed a number of interesting points, no doubt, and you return to your work pleased mentally and refreshed physically. As you take your seat in the comfortable train and coast easily down the side of the mountain, two things are firmly settled in your mind. First, that the Blue Ridge Mountain region is an ideal pleasure and rest resort; and second, that Waynesboro is a thoroughly alive community both from the telephone man’s point of view and from that of any other business man.