by Priscilla Rall

During WWII, evacuation hospitals were located only miles behind the front lines. As our troops moved, the hospitals followed them. One young woman from Thurmont was among these brave nurses giving aid to our wounded.

Mary Catherine Willhide was born on July 8, 1915, to Ross Henry and Elsie Catherine Robinson Willhide of Thurmont. She had two sisters, Helen Willhide Flanagan and Lela “Chubbie” Willhide Lillard. Mary graduated from Thurmont High School and then worked as a nurse at the Frederick City Hospital. Later, she attended Charity Hospital in New Orleans, training to be an anesthetist.

Mary enlisted in the Nurses Corp as a lieutenant, and these excerpts are taken from a letter she sent her family on May 25, 1945. Her big adventure began in October 1943, when she sailed from Boston Harbor aboard the Mauretania. For the first day out, Navy blimps escorted them, alert to any menace from German submarines. After that, they were on their own. The captain zig-zagged to avoid subs, and Mary recorded that the “waves were two stories high.” Three days out, the passengers were told that there was a sub following them, but to everyone’s great relief, nothing happened.

British officers and crew manned the ship. Because of the danger, the captain never left the bridge. The ship held four general hospitals, 400 nurses, and 10,000 mostly American troops. Mary slept in a cabin with eleven other nurses. The cabin had only 10 bunks, so one nurse had to sleep on the floor. The ship arrived at Liverpool on October 16. In the pouring rain, the nurses disembarked, carrying their musette bag, gas mask, and blanket roll. According to Mary, they were “tired, cold and wet.” Then they took a train to their hospital, arriving there October 18. After spending several days resting, rolling bandages, and unpacking their instruments, they opened the hospital November 1. Everyone in her unit was from Texas and very cliquish, so Mary decided to volunteer for an evacuation hospital. Not until April 3 did she learn that she was assigned to detached service and to the 67th Evacuation Hospital near Bristol. There, all hands were just “waiting for the invasion.”

“Never will I forget June 6.” She had been up since daybreak, watching the C-47s with their gliders pulled behind them. They were going over in groups of 100. “The sky was black,” and they were flying just far enough apart as to not hit one another. “Then later we saw them coming back. Some OK, and others with pieces of wing missing or other damage.”

D+9 (June 15) was the day for us to go to the marshalling area. Mary sailed from Weymouth and boarded an L.C.I. (landing craft infantry). Her commanding officer had taken in the 29th Division on D-Day, telling them that the dead were floating as far as two miles from the shore. Mary landed on Omaha Beach on June 17 and was fortunate to leave the L.C.I. on a small motor boat. Her unit spent the night sleeping on the floor at the 91st Evac Hospital. “The artillery and the ack-ack sounded like the 4th of July all night long. All along the road, the infantry was marching to the front. Some sight!”

The next day, they traveled to Sainte Mere Eglise. The soldiers were fighting just a few miles away. “I was most scared when a German plane strafed a cub plane field right beside of ours, killing three soldiers. “Never before have I seen so many mangled bodies. Never did I ever think I would actually walk in human blood, but that is what happened.

“From June 13 at 3 PM until July 17 at 12 noon we admitted over 5,500 patients and operated on more than 2,500. In other words, in 28 days we averaged 90 operations every 24 hours.” They had six operating room tables and six nurses shaving and getting the patients ready for surgery. Fortunately, Polish former POWs carried the stretchers in and out. “Many times we didn’t have enough blood, we needed it so badly.” The hospital was severely overcrowded. One nurse oversaw 30 unconscious patients at a time. Each nurse had a ward of 40 patients with two or three corpsman for each 12-hour shift. “Doctors were so busy, we nurses did the doctors’ work too. We gave blood, plasma and medications… ordered or not.”

“We often say that if the soldiers had not been so patient and good in taking it all, we never could have done it. Sometimes it made you want to cry, especially when we saw one with his legs wounded helping one in the next bed with wounded hands.”

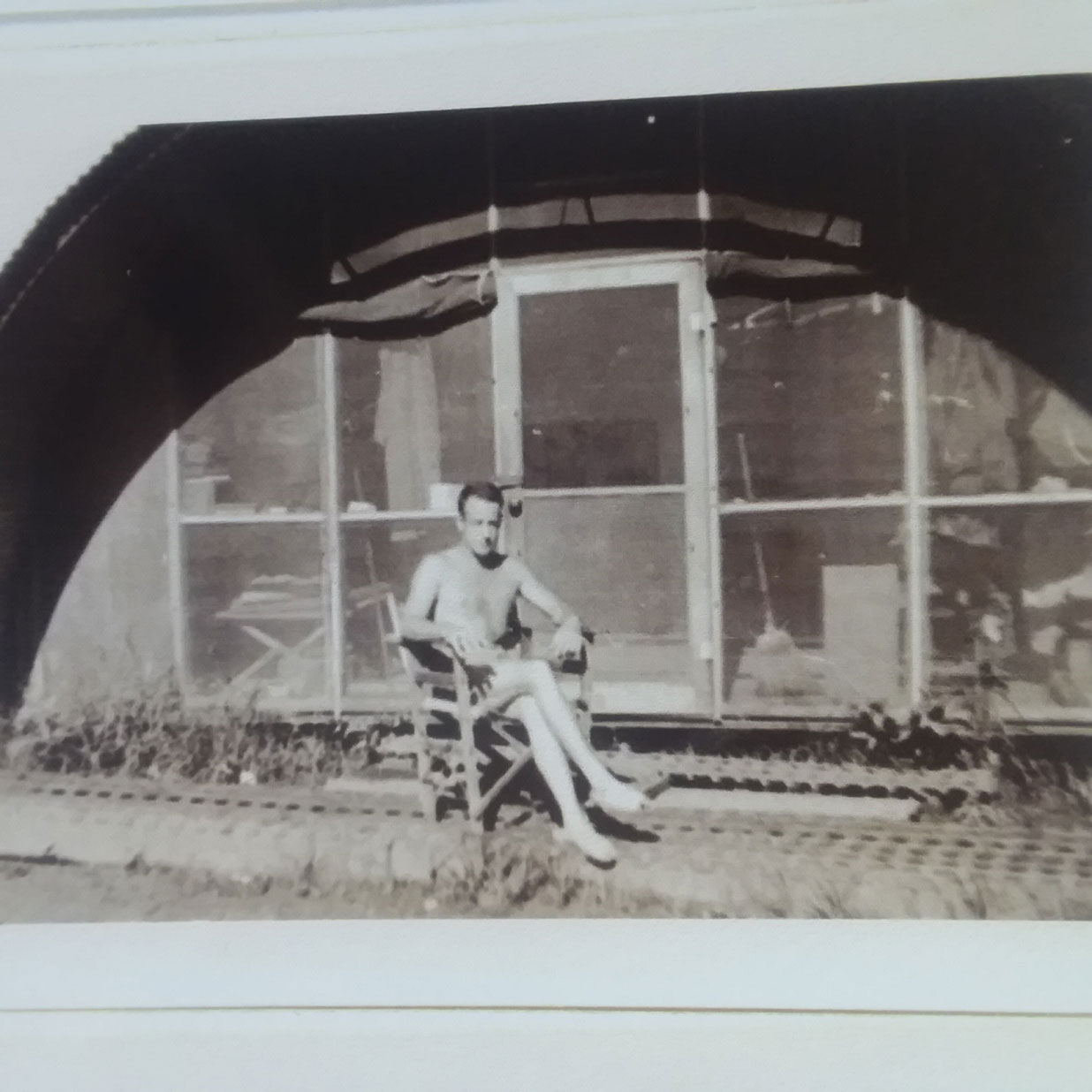

Courtesy Photo of Mary Willhide, Taken in Belgium

Chuck Caldwell and his father, George, came to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on the last day of June 1938 for the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. The town decorated with banners, bunting, and lights, and was so crowded that the Caldwells couldn’t find a room to stay in and spent their first night sleeping in a chicken coop. Chuck, who was fourteen years old, didn’t mind because he had made it to Gettysburg.

Chuck Caldwell and his father, George, came to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on the last day of June 1938 for the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. The town decorated with banners, bunting, and lights, and was so crowded that the Caldwells couldn’t find a room to stay in and spent their first night sleeping in a chicken coop. Chuck, who was fourteen years old, didn’t mind because he had made it to Gettysburg.

Earl A. Rice, Jr. and Mary (Gene) Eugenia (Matthews) Rice were meant to be together. Some of the family members joke that their marriage was an arranged one. Earl and Gene first met in the backyard of the old Rouzer home in Thurmont, from which, the wall paper, now in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House, came. Their mothers—Jessie (Rouzer) Matthews and Helen (Creager) Rice—grew up as next-door neighbors, and were visiting their childhood homes with their first born on the same weekend, sometime in 1924—when someone snapped the above picture. It must have been love at first sight, because they grew up separated by a mountain range and thirty-five miles. They would see each other on occasion during these kinds of weekend visits and dated during their teens and early twenties. They mostly double-dated—the only way Jessie found acceptable—and have many fond memories of those times. Earl sometimes got to borrow his mother’s Lincoln Zephyr, so they got to date in style. Mostly, he came in the Model A that he and his lifelong friend, Henry Steiger, owned together.

Earl A. Rice, Jr. and Mary (Gene) Eugenia (Matthews) Rice were meant to be together. Some of the family members joke that their marriage was an arranged one. Earl and Gene first met in the backyard of the old Rouzer home in Thurmont, from which, the wall paper, now in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House, came. Their mothers—Jessie (Rouzer) Matthews and Helen (Creager) Rice—grew up as next-door neighbors, and were visiting their childhood homes with their first born on the same weekend, sometime in 1924—when someone snapped the above picture. It must have been love at first sight, because they grew up separated by a mountain range and thirty-five miles. They would see each other on occasion during these kinds of weekend visits and dated during their teens and early twenties. They mostly double-dated—the only way Jessie found acceptable—and have many fond memories of those times. Earl sometimes got to borrow his mother’s Lincoln Zephyr, so they got to date in style. Mostly, he came in the Model A that he and his lifelong friend, Henry Steiger, owned together. Earl and Gene lived for a time in California, then onto various assignments, including Pecos, Texas, where these East Coast kids had to contend with such things as spiders and West Texas dust storms. Earl and his crew had to travel separately on a troop train, while the wives followed with one of his fellow officer’s mother as a chaperone, another sign of a different time. Gene made some lifelong friends, with many of the wives demonstrating the love that has endeared her to all those around her. Only a short time after their marriage, Earl and his crew were assigned to their B-29 in the South Pacific Island of Tinian. They had to travel on a troop ship to meet up with their aircraft. Gene headed back home.

Earl and Gene lived for a time in California, then onto various assignments, including Pecos, Texas, where these East Coast kids had to contend with such things as spiders and West Texas dust storms. Earl and his crew had to travel separately on a troop train, while the wives followed with one of his fellow officer’s mother as a chaperone, another sign of a different time. Gene made some lifelong friends, with many of the wives demonstrating the love that has endeared her to all those around her. Only a short time after their marriage, Earl and his crew were assigned to their B-29 in the South Pacific Island of Tinian. They had to travel on a troop ship to meet up with their aircraft. Gene headed back home.

Emmitsburg’s World War I Doughboy statue should be back on its pedestal by mid-March, according to Emmitsburg Mayor Donald Briggs.

Emmitsburg’s World War I Doughboy statue should be back on its pedestal by mid-March, according to Emmitsburg Mayor Donald Briggs.