How I Came to Know My Father ~ Part 1

by Sally T. Grove

Using Her Father Chester L. Grove, Jr.’s Diary and Reflecting on What He Had Written

I was 20 years old, fresh out of college, and in my first year of teaching, a difficult first year. Why did college prepare me so little for my own classroom?

Finally, a break, a time to breathe. I went home for Thanksgiving. At home, I talked with Dad about my living situation and my finances, both in dire straits. A basement apartment, a bathroom that leaked water into the kitchen, and a landlord who lived richly and didn’t care about the problems of his tenants, even as they lived in his own basement. What should I do? Car payments! Dad had warned me not to buy a new car. Not one to listen, I bought a new Honda and was now living the consequences. I loved my shiny red Honda, but the car payments on an $8,000 per year teaching salary were a killer.

On Thanksgiving Day 1977, my father invited me to move back home to relieve the pressure. I could save some money and have some support from my family as I got my feet wet teaching. I cried that Thanksgiving and gave Dad a big hug and kiss, telling him how grateful I was and much I loved him.

A day later, while sifting through a trunk in my family’s unfinished basement, I found a small stenographer’s notebook, its brown cover worn, well-traveled, edges frayed. I opened the notebook slowly, deliberately. Its contents were gradually revealed, like the plot of a mystery novel. As the practiced and perfect handwriting came into focus, I knew this writing to be my father’s.

“On April 15, 1943, I took my examination for the U.S. Army. It was on this day that I ate my first sandwich consisting of baloney.”

Was that my father? I had never seen him eat a baloney sandwich. In fact, I know his menu by heart: vegetables consisting of peas, corn, baked beans, and any kind of potato; meats, always dry and over-cooked—these were his meals and ours—and Friday night was tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwiches. These are the foods that Dad liked, and these are the foods that we ate and loved. We ate like our father, all six of us, much to my Mom’s chagrin.

“The morning of April 22, my last day home, I went up Carroll Creek and caught seven beautiful trout, my last as a civilian.”

When our family visited “Poppy in Frederick” when I was small, I used to stare at the stuffed fish that adorned his dark, dusty, shadowed walls. The fish hung as a testament to his youth and his sense of adventure. My grandfather was a fisherman, and he taught my dad to fish. I have a great picture of my father (shown left), standing with a fist full of fish fanned out for the photographer’s film. Was this a picture of Dad on the day my grandfather caught the big one?

“Our train ride took us through Western Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama… We arrived at our new station, Fort McClellan, a very tired bunch of rookies… I got along very well eating most everything we got for meals, although not liking it very much…”

His first big adventure via train—how exciting! With six kids, our family’s adventures now consisted of camping in Western Maryland or a week in Ocean City. We rode bikes each morning on the boardwalk and had pancakes at Happy Jack’s Pancake House. At least in Ocean City, Dad ate what he wanted.

“I took the Air Cadet exam the 12th week of basic. The passing grade for the cadet exam is 83 and I made 100%, the 3rd highest grade… On February 16th, 1944, I made my first flight at the school and by March 11th, I had completed 10 hours of flying. I really loved flying…”

Twenty-one years old and learning to fly. I didn’t know Dad had flown planes! Why didn’t he tell us? I remember when we were little, Dad took us to “Penny-A-Pound” Day at the local airport. For a penny a pound, we could go on an airplane ride. I remember being frightened and not wanting to go. Dad convinced me it would be okay. Once in the air, I couldn’t get enough of flying. The houses and streets looked like a miniature Christmas village below. No wonder Dad loved flying.

“… arrived at Santa Anna Army Air Base on the 23rd, after a very exciting trip across the U.S., my first. After taking the test for three straight days, I was a classified pilot but then the tragedy came. An order came from Washington, calling back all cadets who were former ground force students and so my dreams of flying were crushed on April 1, 1944 by a single piece of paper.”

I guess that’s why my father didn’t tell us…his dream was shattered. What other dreams did Dad have for his life? Most of what I know of my father revolves around the time he spent with his family. Were we part of his life dream?

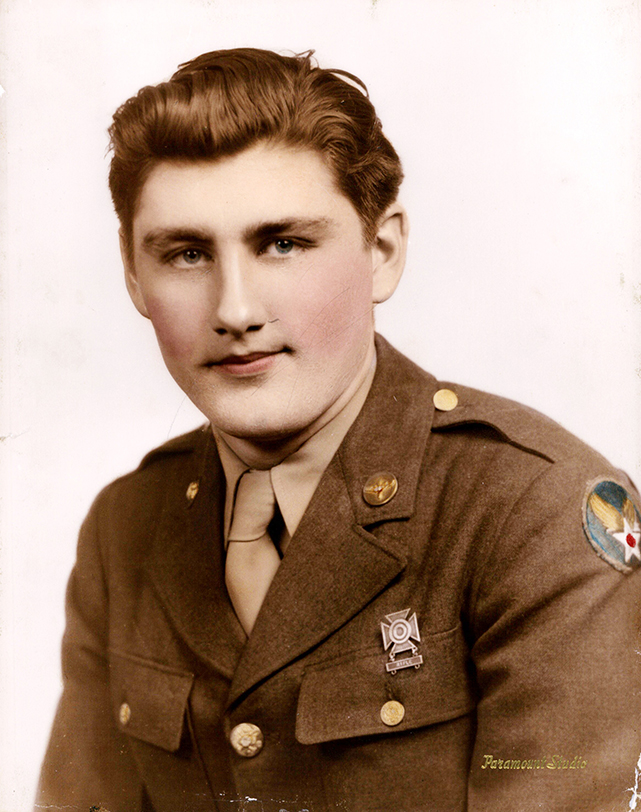

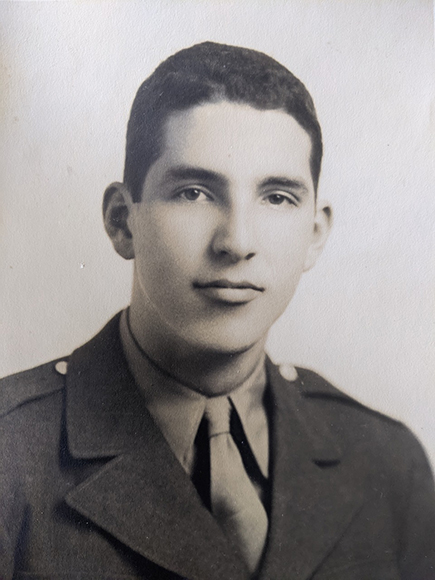

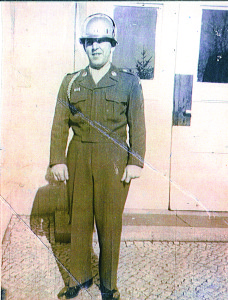

Courtesy Photo of Chester L. Grove, Jr. in Uniform

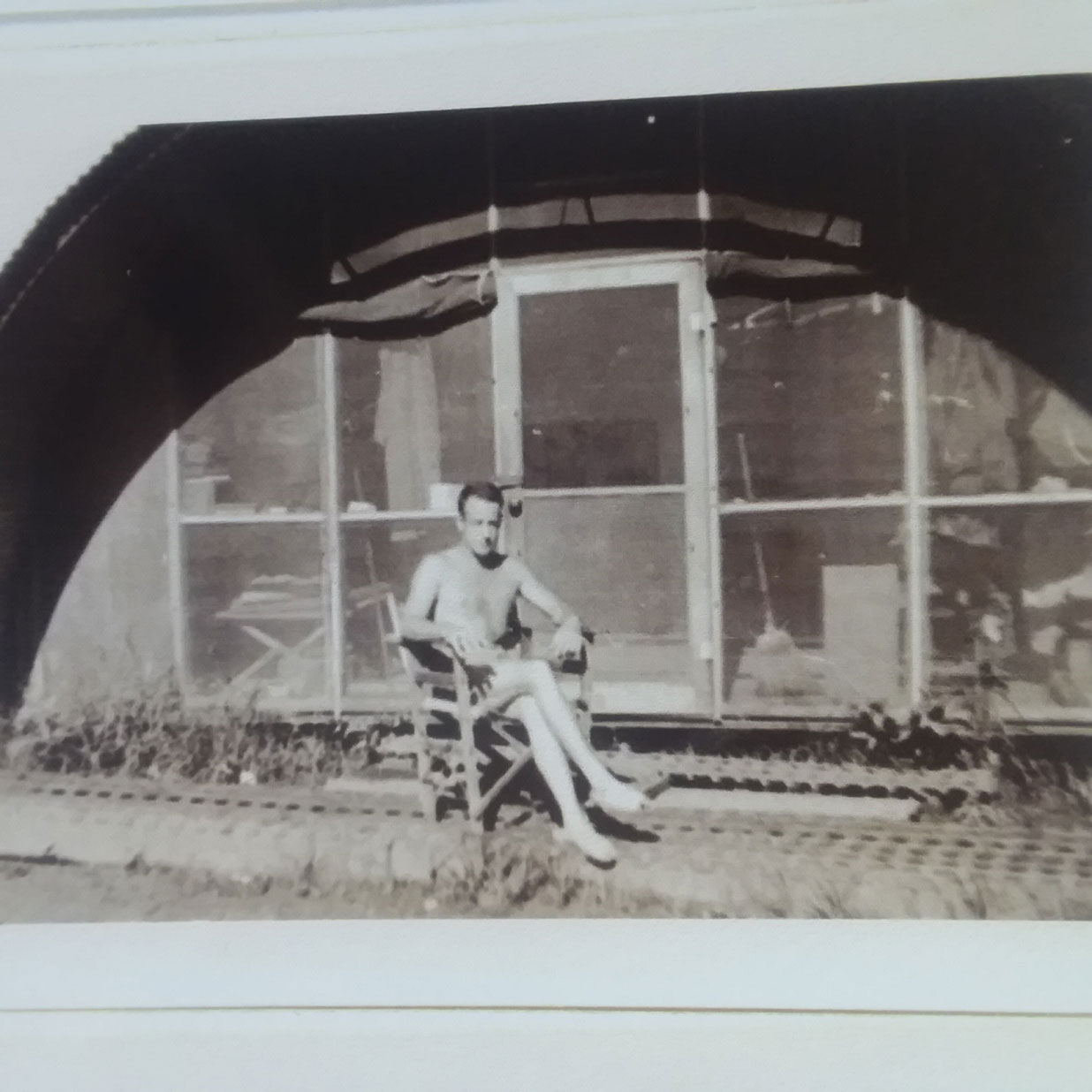

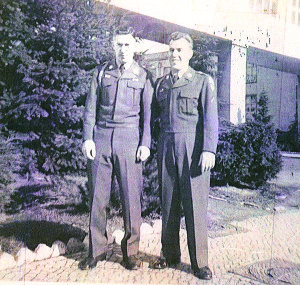

Courtesy Photo

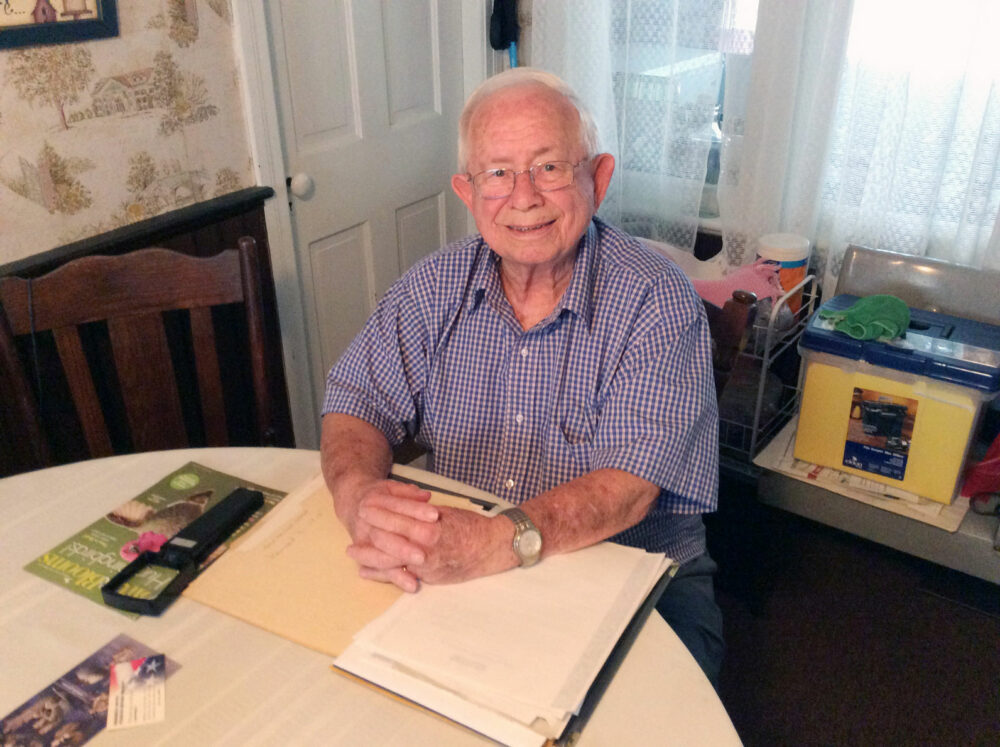

Born in 1927, at home in Emmitsburg to Gertrude and Hubert Joy, was a baby boy they named Joseph (Joe). Joe was one of eleven children: Bobby, Johnny, Kenny, Donald, Mike, Gloria, Patrick, Delores, Jerry, and Rosemary (passed away at three days old). Joe went to school at Saint Euphemia’s in Emmitsburg; he quit school at the age of fifteen and moved to Baltimore, Maryland. He went to work as a painter’s helper at S&A Williams, a painting contractor. He worked for them for about five years, when he decided to go work for his father, who went into business for himself. Joe liked to hunt and would make trips to Emmitsburg, where he would hunt rabbits, pheasants, and squirrel. He said he was not much of a deer hunter and has never killed one. He said he remembers his first automobile was a 1950 Pontiac. He stated that he doesn’t know how many cars he has had, but he’s still driving the one he bought in 1992, and at his present age of eighty-eight, he plans on driving as long as he is able.

Born in 1927, at home in Emmitsburg to Gertrude and Hubert Joy, was a baby boy they named Joseph (Joe). Joe was one of eleven children: Bobby, Johnny, Kenny, Donald, Mike, Gloria, Patrick, Delores, Jerry, and Rosemary (passed away at three days old). Joe went to school at Saint Euphemia’s in Emmitsburg; he quit school at the age of fifteen and moved to Baltimore, Maryland. He went to work as a painter’s helper at S&A Williams, a painting contractor. He worked for them for about five years, when he decided to go work for his father, who went into business for himself. Joe liked to hunt and would make trips to Emmitsburg, where he would hunt rabbits, pheasants, and squirrel. He said he was not much of a deer hunter and has never killed one. He said he remembers his first automobile was a 1950 Pontiac. He stated that he doesn’t know how many cars he has had, but he’s still driving the one he bought in 1992, and at his present age of eighty-eight, he plans on driving as long as he is able. Joe met Betty Ruth Luster, who lived across the street from where he was residing in Baltimore, and they later were married. Betty and Joe had three children: two girls and one boy—Karen, Kathy, and Steve. They raised their family in southwest Baltimore, close to St. Agnes Hospital. Betty passed away at the age of seventy-three from cancer while they were living in a basement apartment at their daughter’s house. Their daughter was a nurse and was helping to take care of Betty. Joe’s daughter was murdered by a male friend of hers, and Betty died about three months later. The house was sold, and Joe went to live with his son, Steve, for three months; Steve’s house wasn’t large enough to accommodate everyone. Joe has resided (for the past six years) in that area at an apartment complex run by Catholic charities, called DePaul House.

Joe met Betty Ruth Luster, who lived across the street from where he was residing in Baltimore, and they later were married. Betty and Joe had three children: two girls and one boy—Karen, Kathy, and Steve. They raised their family in southwest Baltimore, close to St. Agnes Hospital. Betty passed away at the age of seventy-three from cancer while they were living in a basement apartment at their daughter’s house. Their daughter was a nurse and was helping to take care of Betty. Joe’s daughter was murdered by a male friend of hers, and Betty died about three months later. The house was sold, and Joe went to live with his son, Steve, for three months; Steve’s house wasn’t large enough to accommodate everyone. Joe has resided (for the past six years) in that area at an apartment complex run by Catholic charities, called DePaul House.