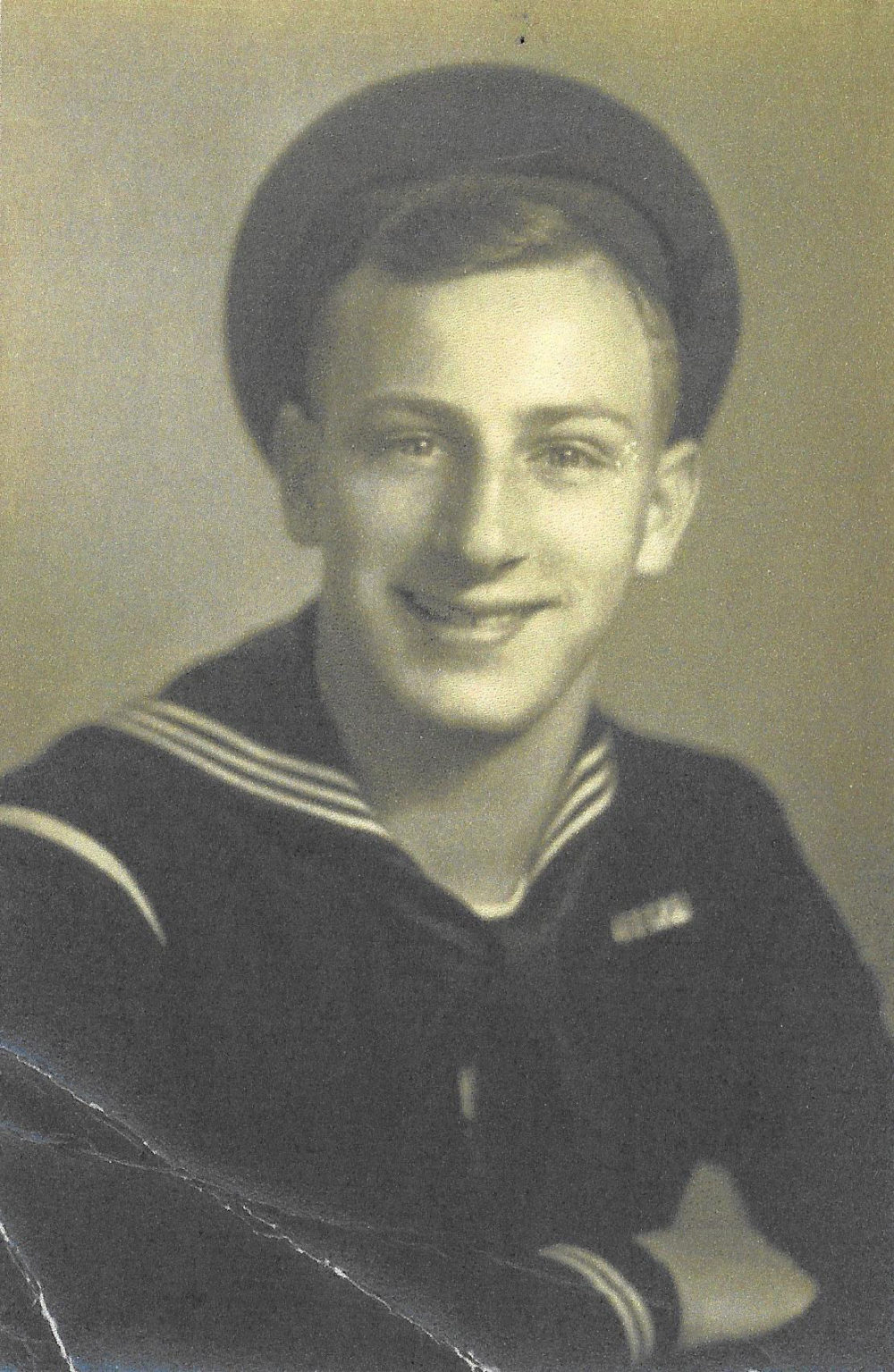

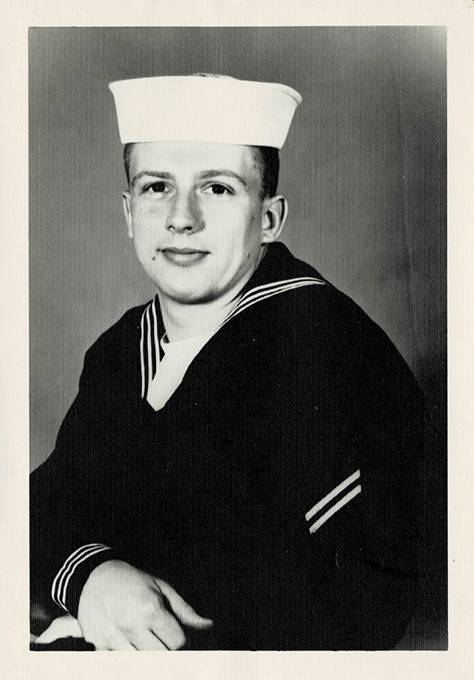

Seaman John Ballenger

by Richard D. L. Fulton

Four years on the Saratoga

John Ballenger’s adventures aboard the U.S.S. Saratoga, the sixth ship in the Navy that had been named after the 1777 Battle of Saratoga – which marked a turning point in the American Revolution – began in 1960 when he sought to avoid the draft, and thus… the Army, and instead he then volunteered to join the Navy.

It was a close call, soon-to-be Seaman Ballenger stated. Within two weeks of entering basic training, he received a draft notice. The advantage of not being drafted, he said, was that if an individual was drafted, the draftee had to do whatever the Army assigned to them, but if an individual volunteered, “You got to do what you wanted to do.”

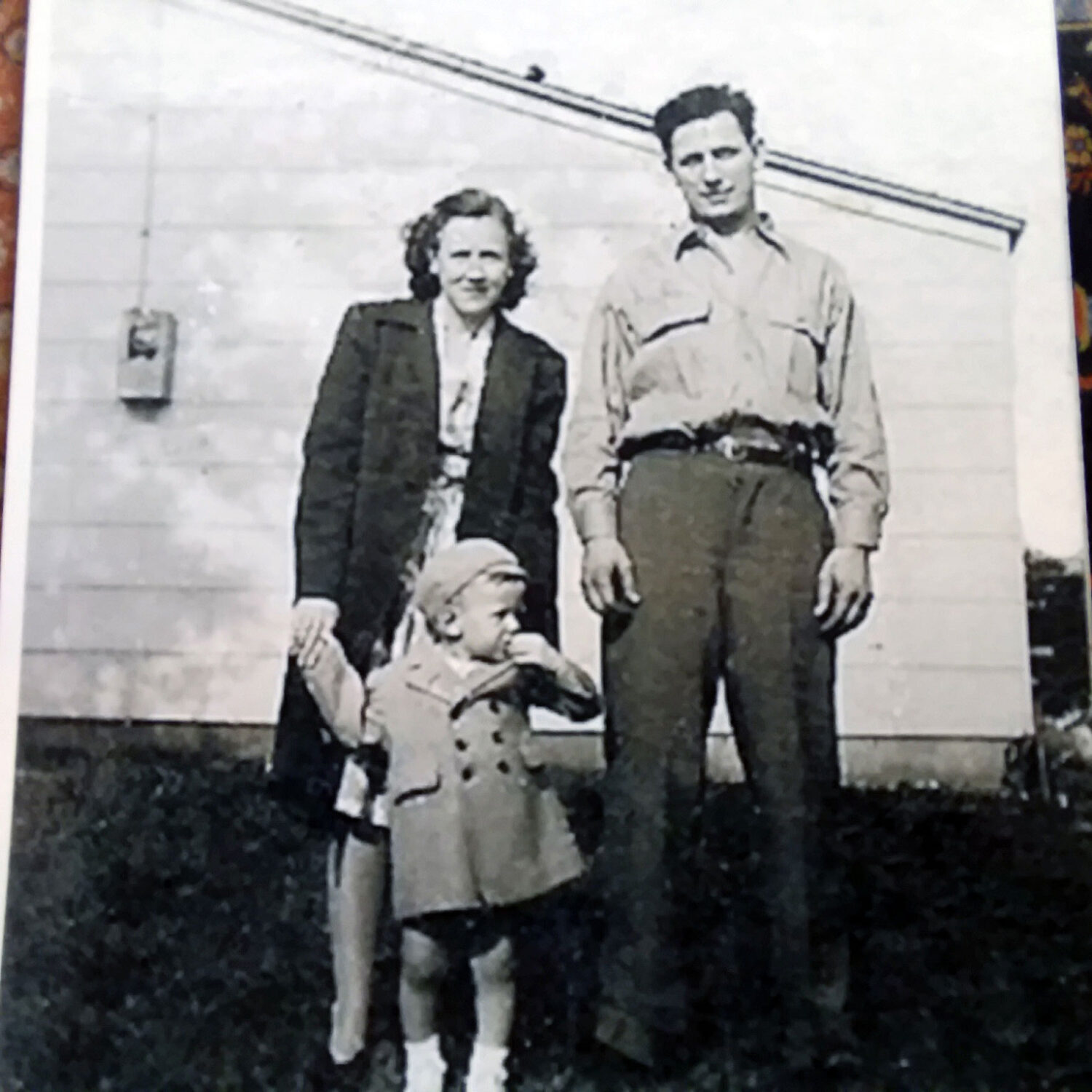

Ballenger resided in Laurel at the time with his parents, where his father also owned and operated the regionally renowned Ballenger Buick (Seaman Ballenger worked at the dealership before ultimately inheriting it, upon his father’s death.).

Following his induction into the Navy at Andrews Air Force Base (the home of “Air Force One” since 1961), he ultimately was assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, in Michigan, for basic training, and then on to the Mayport Naval Station, Jacksonville, Florida, where he was assigned to the Saratoga.

The command wanted Ballenger to serve on the flight deck crew, but he wanted and was approved to serve as a catapult-and-arrest mechanic—the catapults being the means by which the jets are launched from the carrier, and the arresters are the means by which the incoming planes are stopped on the deck. He was also responsible for assuring that jets preparing to take off had the appropriate load of fuel and confirmed that the plane’s load met weight standards.

In 1962, the Saratoga was ordered to proceed to Guantanamo Bay along with two other carriers during the “Cuban Missile Crisis”—a 13-day standoff between the U.S. and the USSR over nuclear missile bases being installed by the Russians in Cuba. Ballenger said the Saratoga and the others were prepared for the worst. They all had nuclear missiles onboard. If the carriers had been forced to arm the jets and use the missiles, “Cuba (as we know it),” he said, “wouldn’t exist today.”

After the Russians backed down, the Saratoga was off to the Mediterranean, during which time Ballenger was able to witness the kind of things that could happen on deck when things went wrong.

During one incident which turned out to be more heart-stopping than catastrophic was when an improperly secured bomb dropped off the wing of one of the jets during its take-off and landed on the deck. Fortunately, it didn’t detonate.

If the catapults did not function properly, a plane could nose-dive into the sea off the bow of the ship, and if a jet—generally coming in at 150 miles-per-hour—missed the arresters, it could result with fatal outcomes.

Ballenger said that one plane attempting to land missed the arresters, and the pilot throttled up and took off, enabling the pilot and co-pilot to eject (having lost their landing gear). Somehow, he said, the co-pilot was killed in the effort. During a second incident, another jet came in and missed the arresters and crashed into a line of jets on the flight deck, setting them afire. Fortunately, Ballenger stated, the planes had their bombs removed and taken below deck before the crash. “It was a terrible crash,” he said. “We lost a few people.”

But the Saratoga did avert being deployed to Vietnam during Ballenger’s service, and the sailors aboard, were instead given opportunities to enjoy a number of Mediterranean countries, including Venice, Italy, France, and Turkey.

Ballenger was discharged in 1964, and married his wife, Linda Ballenger in 1977, and sold Ballenger Buick in 1989, subsequently buying the farm upon which they presently reside in northern Frederick County. They have three daughters, Jessica, Cynthia, and Emily, and one son, John III. Ballenger retired from Lonzo Bioscience in 2017 after having been employed at that facility for 12 years.

Seaman John Ballenger