A serial fiction story for your enjoyment

written by James Rada, Jr.

1: Breakdown

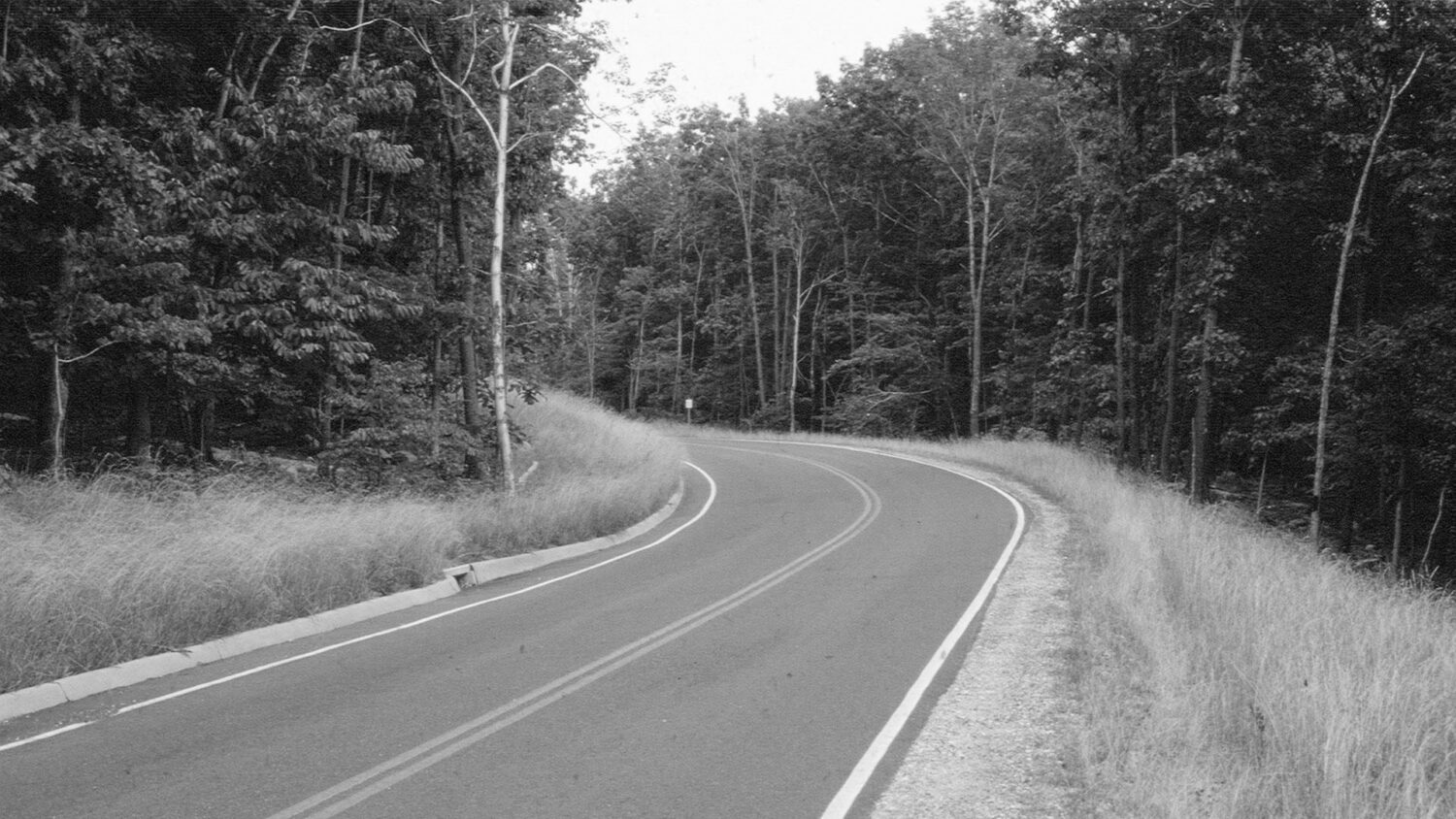

Stacy Lawrence glanced anxiously from the dashboard to the winding road ahead of her, as the temperature needle steadily climbed. She had been a teenage mom, but now she was trying for a fresh start. The rising gauge reminded her, though, that you couldn’t always escape your past.

Raised in Gaithersburg, where the cost of living was skyrocketing, she had wanted to stay in the county for the good schools, hopeful that her son could get a good education. Unfortunately, COVID-19 cost her her job as a veterinarian assistant and apartment lease, forcing her to pack up the car and leave for some place affordable to live.

She and Peter headed out on an uncertain path, northwards. They drove north on Interstate 270, leaving Montgomery County. As she drove through Frederick, she took some side roads to explore towns on the map as a possible place to live.

However, she stopped in Catoctin Mountain Park, just to relax. She felt drawn to its beauty—it was like nothing was weighing her down. She and Peter hiked one of the trails up to a scenic overlook that took her breath away. She had seen nothing like this in Montgomery County.

Once they were back in the car and driving further up the mountain, her car struggled. The engine sputtered, and the temperature gauge rose. Before long, the car came to a stop. Stacy had no one to call for help, and she wasn’t a member of AAA. She and Peter were stranded in the middle of nowhere. The scenic vistas and country setting no longer seemed so inviting. She did not know what to do, and the sun was setting.

Stacy sat on the side of the road, cursing her luck. She knew she should have gotten the car checked before leaving Gaithersburg, but she couldn’t afford it. She leaned her head back against the headrest, closing her eyes and taking deep breaths, trying to calm herself down. She had been through worse than this. She was a survivor.

“It can’t be that bad, Mom,” Peter said.

She rolled her head to the side and looked at the 10-year-old. What should she tell him? He wasn’t dumb.

“Probably not. I just need to consider what to do,” she answered finally.

“We could walk back to the visitor’s center.”

“They closed at five o’clock.” Besides, she would rather not walk on the twisting road with narrow shoulders. A careless driver could easily hit them.

However, she knew they couldn’t stay here on the side of the road, either. It was getting dark, which would make the road that much more dangerous.

She turned to her son and said, “I’m going to walk further up the road and see if I can find a house. I’ll call you if I do, so don’t play games and run the battery down on your phone.”

“I can come with you.”

Stacy shook her head. “No, you stay here in the car with the doors locked. If anyone comes by, talk to them through the window. See if they know someone who can help us and call me.”

Peter nodded. “Be careful.”

She nodded and kissed him on the cheek. “I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

Stacy got out of the car and started walking uphill on the road shoulder. She was hoping to find a gas station, but she would settle for a house where someone was home. All she saw were trees and rocks. Occasionally, a car passed, but none of them slowed to help her. They probably thought she was a hiker.

After a while, she saw a light in the distance. She could make out the silhouette of a farmhouse and hoped for a phone to call for help. As she trudged up the dirt driveway, chickens clucked and the smell of pork drifted from the porch, where a man sat in a rocking chair eating.

“Hello,” Stacy said. “Can you help me? My car broke down on the road, and I need to call a tow truck. I have no idea who to call.”

The man set down his sandwich and waved her forward. “Hope you haven’t been walking long on the road. It can be dangerous. Some idiots take the turns too fast, thinking it will get them into Thurmont faster.”

“I was nervous, but I didn’t see many cars.”

“Would you like something to eat? I make a great pork barbeque.”

Stacy shook her head. “No, thank you. I left my son in the car. I’d like to get back to him.”

The man wiped off his mouth. “Well, let me get my keys, and we’ll drive down and see what’s wrong.”

“Are you a mechanic?” Could she be that lucky?

The man chuckled. “You have to be a bit of everything around here. I can keep my tractor and truck running. If you don’t need new parts, I might be able to help.”

“Thank you, Mr. …”

“Hennessey. Robert Hennessey, but people call me Bobby.”

He opened the screen door, reached inside and grabbed his keys, which must have been on a hook next to the door.

“I’m Stacy Lawrence,” Stacy told him.

Bobby hopped off the porch. “Nice to meet you. Truck’s over here.”

They walked around the side of the farmhouse. Bobby’s truck was an older model, probably older than Stacy’s car, but she bet he kept his car maintained.

They climbed into the cab, and Bobby started the engine. He turned the truck around and headed toward the road.

“This looks like a nice farm,” Stacy said.

“It’s been in my family for generations, but that might change soon. I’m the last one left.”

“You don’t look that old.”

He smiled. “I don’t think I am, but there’s no next generation getting ready to take over. Truth is, I have thought about selling it.”

“Seems like that would be a shame.”

He shrugged. “Maybe, but I never planned on being a farmer. I was a financial consultant in D.C.”

“What happened?”

“My parents got COVID. I came back to take care of them, but then they died, and I wound up staying here.”

“You could sell it,” Stacy suggested.

“I could, but I feel an obligation to my parents to keep it going as long as I can.”

Stacy couldn’t imagine feeling that type of obligation to her parents. They had kicked her out of the house when they found out she was pregnant. She had moved in with Jason, Peter’s father, and they had lived in the basement of his parent’s home. They had moved out of there as soon as they could.

Bobby passed Stacy’s car and found a place to turn around. Then, he came up behind it and put his hazard lights on. They got out of the truck, and Stacy hurried over to make sure Peter was all right.

Bobby had her unlatch the hood, and he lifted it up to look inside. After a few minutes, he looked under the car.

He then stood up and shook his head. “I’m surprised you got this far in this heap.”

“That bad?”

“You’re dripping oil and have a leaking radiator. It also looks like a few other things are either ready to go or have gone. When was the last time you had this car serviced?”

“The last time I had enough money to do it, and that was a while ago.”

Bobby sighed and said, “Well, I’m sorry, but it’s not an easy fix. It will need to go into the shop.”

“For how long? I was heading to Harrisburg.”

“Given that it’s Friday, you won’t find anyone to look at it until Monday, probably.”

Stacy closed her eyes and slowly shook her head. She wanted to cry. How was she going to afford the repairs, plus the hotel?

Bobby called for a tow truck and waited until it came. Then he talked with the driver. He walked back to where Stacy and Peter waited, sitting on a hill beside the road.

“Jack says you can ride with him back to Thurmont. He’ll drop you off at the Super 8 Hotel. Tell them I told you they would give you their best rate. They’ll take care of you. Jack’s a good guy, too. I talked him into taking a look at the car tomorrow, but it probably won’t be until Monday at the earliest before your car is ready.” He paused and smiled. “Welcome to Thurmont.”

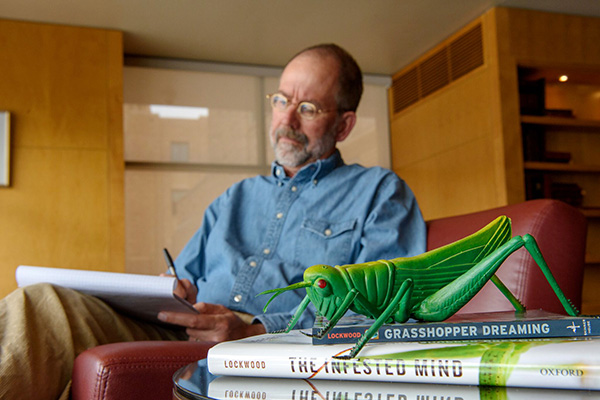

When our National Parks were first established, well over a century ago, painters and photographers created works that inspired Americans and people from around the world to journey and visit those areas and to generate interest in the parks. That practice lives on to this day. The National Park Service (NPS) still reaches out to potential “artists” through its Artist-In-Residency (AIR) program, which is available at over forty different locations.

When our National Parks were first established, well over a century ago, painters and photographers created works that inspired Americans and people from around the world to journey and visit those areas and to generate interest in the parks. That practice lives on to this day. The National Park Service (NPS) still reaches out to potential “artists” through its Artist-In-Residency (AIR) program, which is available at over forty different locations. The Camp Greentop Stable in Catoctin Mountain Park has fallen into disrepair. Built in 1980, the stable housed horses used by National Park Service Law Enforcement Rangers to patrol trails and remote areas of Catoctin Mountain Park. As park visitation increased, park rangers were re-directed to other park missions, and the Catoctin Mountain Park Volunteer Horse Patrol became the “eyes and ears of the park.” In addition to patrol, the Horse Patrol maintained trails and cared for the horses and stables.

The Camp Greentop Stable in Catoctin Mountain Park has fallen into disrepair. Built in 1980, the stable housed horses used by National Park Service Law Enforcement Rangers to patrol trails and remote areas of Catoctin Mountain Park. As park visitation increased, park rangers were re-directed to other park missions, and the Catoctin Mountain Park Volunteer Horse Patrol became the “eyes and ears of the park.” In addition to patrol, the Horse Patrol maintained trails and cared for the horses and stables.

Jeremy Murphy (pictured right) was born and raised in Emmitsburg, graduating from Catoctin High in 1998. He visited both Catoctin Mountain Park and Gettysburg National Military Park on field trips and summer trips, never realizing that he would grow up to become the chief law enforcement officer for the Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Site.

Jeremy Murphy (pictured right) was born and raised in Emmitsburg, graduating from Catoctin High in 1998. He visited both Catoctin Mountain Park and Gettysburg National Military Park on field trips and summer trips, never realizing that he would grow up to become the chief law enforcement officer for the Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Site. James Rada, Jr.

James Rada, Jr.