The Camp Letterman Story

Richard D. L. Fulton

On July 1, 1863, a massive and deadly storm descended upon Gettysburg, with the thunder being provided by more than 600 cannons and the fierce lightning being the result of the firing of more than 140,000 rifles.

The storm was caused by the violent convergence of the Union Army of the Potomac, under the command of General George G. Meade, and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, under the command of General Robert E. Lee.

By the end of July 3, the fields of Gettysburg had become littered with more than 50,000 dead and wounded—the highest number of human casualties that have been sustained by American forces in a single battle before, during, or since the engagement at Gettysburg.

Many of the wounded and dying were housed in local homes and churches, impromptu field medical tents, and at a special military medical compound known as Camp Letterman. However, in the case of the Confederate Army, its casualties who had not been abandoned or captured on the field were loaded aboard wagons to commence with their painful trek back to Virginia.

Camp Letterman was ordered to be established on July 4, the day after the battle had subsided, by Assistant Adjutant General Seth Williams. The facility was to be named Camp Letterman, in honor of Doctor Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director for the Army of the Potomac, according to Gettysburgdaily.com.

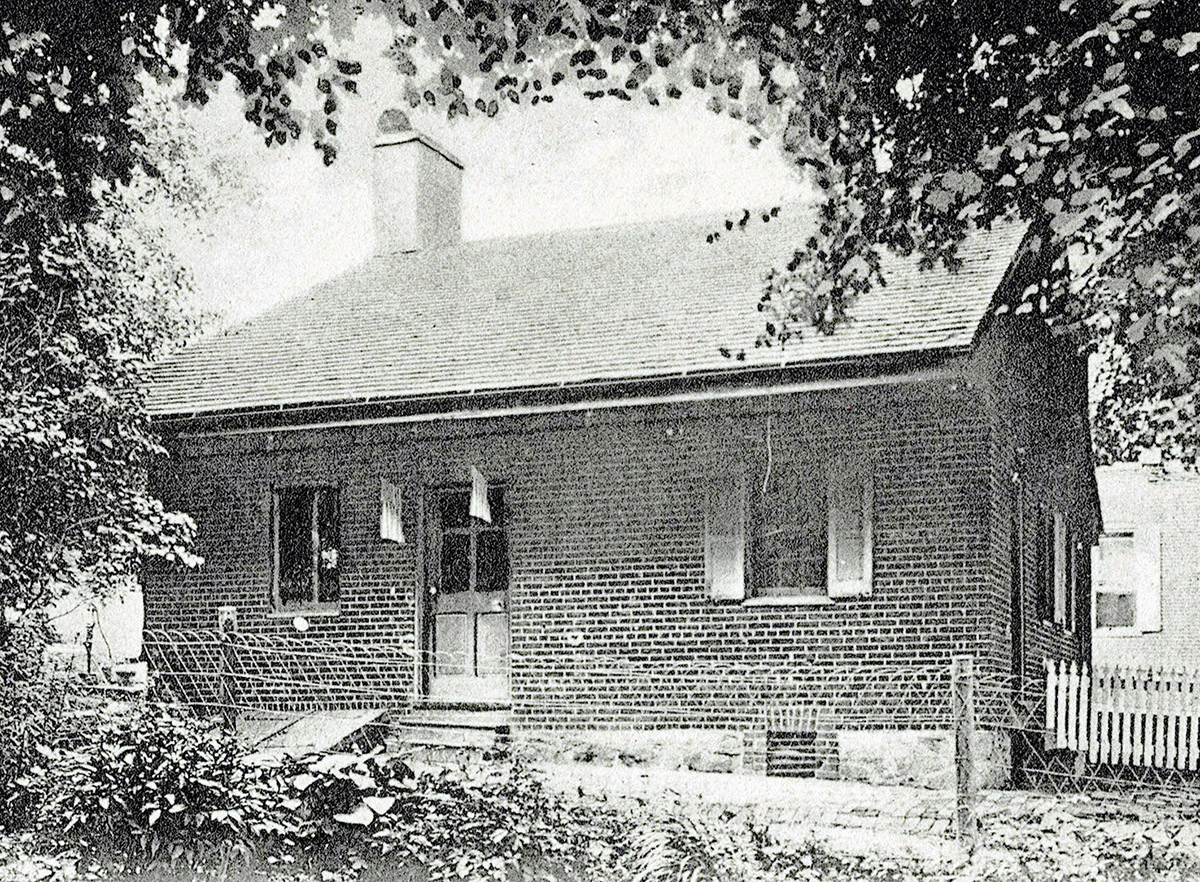

The site selected was situated along York Road, just east of Gettysburg, near the east of the site of the present Giant grocery store shopping center, and had consisted of some 80 acres in extent.

The property involved was then known as the George Wolf farm, which had been selected, according to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, because the farm was located on high ground, with “abundant spring water, and (located in) close proximity to the York Road and Gettysburg Railroad.”

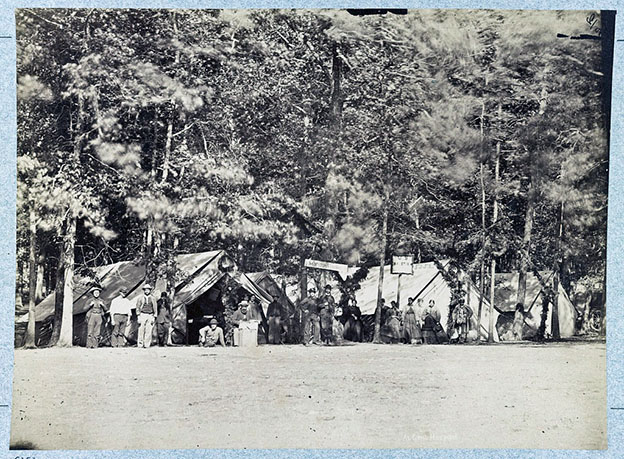

The portion of the farm utilized was not yet cultivated at that time and contained a significant stand of trees, which provided an abundance of shade for the encampment. Surgeon Henry Janes served as the doctor in charge of Camp Letterman.

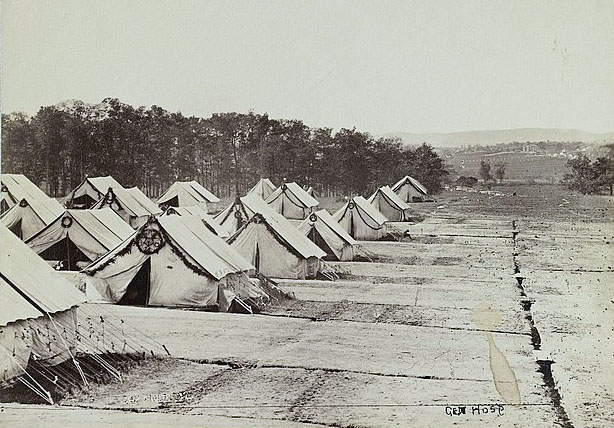

Further, nurse Sophronia E. Bucklin, author of In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War, noted that there were 500 “large hospital” tents erected in the camp (of which, she wrote, had even increased in number over time)” in rows with well-trodden, dirt walkways, established to minimize the mud. Each tent could house 12 patients, as noted by Battlefields.org (American Battlefield Trust).

Torrential rain fell in the wake of the battle, adding to the misery contained within the sprawling field hospital. As an aside, Bucklin noted that during heavy rain, “muddy rivulets (flowed) through our tents, (and we were) obliged in the morning to use our parasol handles to fish our shoes from the water before we could dress.”

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine (NMCWM) further stated on its website (civilwarmed.org) that the hospital included “a dead house, embalming tent, cemetery, cookhouse and warehouse tents.”

Some 400 individuals, consisting of military staff and volunteers (including the U.S. Sanitation Commission and the U.S. Christian Commission), served at the encampment.

Npshistory.com noted, “Doctors, nurses, hospital stewards, ward surgeons, wound dressers, and night watchmen worked dawn to dusk every day.”

The NMCWM further noted that soldiers who had improved, but were in need of additional care, were transported by rail to hospitals in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

The Gettysburg Times noted in a story they published on September 2, 1949, that Camp Letterman had treated more than 20,000 Union and Confederate casualties.

Bucklin wrote that more than half were Confederate casualties, which she had described as having been “grim, daunt, ragged men—long-haired, hollow-eyed and sallow-cheeked.”

Feeding the casualties and staff was at first a very unpleasant experience.

Bucklin wrote that, initially, “Hunger only made edible the wretched food which was spoiled in its long-heated journey over the dusty road from Washington.”

However, the camp was soon supplied with a new kitchen, along with ”monster” stoves and huge cauldrons.

Bucklin noted that one of the primary rules of conduct required of staff and volunteers was that the Confederate casualties were to be treated equally as those of the Union, further noting that many Union soldiers had remarked on how well they had been treated by the medical staffs in prisoner-of-war camps, in which they had found themselves in the South.

Bucklin further wrote that one individual employed for helping the wounded in the camp had been discharged because she “refused to give food or aid or drink” to any of the Confederate wounded, “regarding them as wanton murderers of her beloved husband.”

Intolerance was not tolerated in the hospital camp.

More than 1,200 of the casualties perished at the camp, according to Michael Mahr, an education specialist at the NMCWM.

Bucklin noted that “many more of the rebels died than of our own men.” Further noting that, in one instance, “of the twenty-two rebels who were brought into my ward at one time, thirteen died, after receiving the same care that was given to our men.”

Amputations of severely damaged arms and legs were not uncommon in the camp. Emergingcivilwar.com noted on its website, “Removed limbs would either be discarded and buried on site, or sent to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C., as a specimen for study.”

Matthew Atkinson, Gettysburg National Military Park (npshistory.com), further wrote that a letter written by Union soldier Frank Stoke to his brother had stated, “Those who die in the hospital are buried in the field south of the hospital…The dead are laid in rows with a rough board placed at the head of each man… The amputated limbs are put into barrels and buried and left in the ground until they decomposed, then lifted and sent to the Medical College at Washington.”

Camp Letterman was dismantled in November 1863. Emergingcivilwar.com wrote on its website: “In November 1863, Camp Letterman all but vanished from the visible landscape. Union dead were exhumed and either sent to family or buried in the Gettysburg National Cemetery (except for the bodies of black Union soldiers who had died in the camp, since black soldiers were not permitted at that time to be buried in the National Cemetery).”

Today, a roadside marker denotes the general location of the medical encampment. The marker was a “wide, upstanding piece of granite with a metal tablet” and was the first “Great Rebellion”-related marker installed east of Gettysburg. The monument was placed within the woods in which the camp had been located.

Highly recommended to the reader is Sophronia E. Bucklin’s fascinating account, published in her book, In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War, which is accessible in its entirety online at Library of Congress website.

For a more definitive account of Camp Letterman, refer to “War is a hellish way of settling a dispute” by Matthew Atkinson, Gettysburg NMP, at npshistory.com.