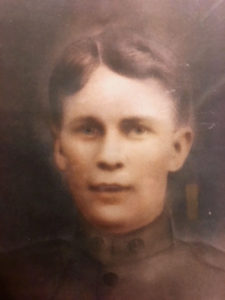

Clifford Stitely Died Helping Others 100 Years Ago

by James Rada, Jr.

On November 6, 1918, the peace talks between the Allies and Germans had been completed. Men who had fought so hard for years looked forward to the peace that would take place on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive had started on the Western Front on September 26, and it continued as peace fast approached. It was the largest in United States military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. It was the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I. The men were worn down and tired. Over the forty-seven days of the battle, more than 55,000 soldiers lost their lives, including 26,277 Americans.

Clifford Stitely of Thurmont was a young private in the Army. He had been inducted into the 79th Division at Camp Meade just four months earlier.

“The departure of 110 Sammies for Camp Meade on Saturday wrung tears from many women and men alike,” the Frederick Post reported. “They tried bravely to put up a cheerful front to their sons, brothers and sweethearts, but many eyes were red and many cheeks wet before the final goodbyes had been said.”

The newspaper reported that a crowd of 3,000 showed up to see the draftees off at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot.

With less than a month of training at Camp Meade, Private Stitely boarded a ship in Hoboken, New Jersey, and headed overseas to France as part of Company B, 312th Machine Gun Battalion.

In France, he fought in the Avocourt Sector and Troyon Sector of the Meuse-Argonne. His great-nephew Bill Bollinger said that on November 3, 1918, “He was on a detail picking up the wounded, and he was killed by artillery fire.”

Records show that Stitely didn’t die right away. He was taken to a field hospital where he died three days later, with less than a week to go before peace was declared.

His parents, Jacob and Mary, must have wondered why they hadn’t heard from their son, especially after peace was declared. As the days turned to weeks, they might have suspected the worst, but luckily confirmation did not arrive until after Christmas. A telegram arrived on December 28 with the news that Clifford had died “under honorable conditions,” trying to help others.

Clifford is one of eleven men that Thurmont lost during World War I. His name is inscribed on the WWI Monument in Memorial Park.

Roll of Honor

Thurmont’s lost heroes of WWI:

- Louis R. Adams

- Murry S. Baker

- Benjamin E. Cline

- Edgar J. Eyler

- William T. Fraley

- Roy O. Kelbaugh

- Jesse M. Pryor

- Clifford M. Stitely

- Raymond L. Stull

- Stanley M. Toms

- James Somerset Waters

Photo Courtesy of Bill Bollinger

Easter at Camp David

Easter at Camp David