1921 Thurmont School’s First 7th Grade Graduation Ceremony

In 1921, the Thurmont community had two school graduations: one for the high school students and one for the grade school students.

“For the first time in the history of our schools, a Seventh Grade public commencement will be held in Town Hall, this place,” the Catoctin Clarion reported at the beginning of June 1921.

The high school and grade school were both in the same building on East Main Street, but they taught different curricula. The two operations had originally merged into a consolidated school in 1910; but after a severe windstorm damaged the building in 1914, a new school was constructed on 1916.

By 1921, the staff had decided that the grade-school students deserved a ceremony to mark them moving from grade school to high school. The first grade school commencement was held on June 4 at 8:00 p.m.

Although primarily for Thurmont students, students from other schools were allowed to take part. The seventh graders graduating included 31 students from Thurmont, 4 from Sabillasville School, 3 from Grove Academy, 3 from Foxville School, and 2 from Catoctin Furnace School.

The program was under the direction of L. D. Crawford, a teacher at the Thurmont School.

“Mr. Crawford is a teacher loved by every student who enters his classroom and is one who gets results in whatever he undertakes,” the Catoctin Clarion reported.

All the students sang “Sailing” as the opening song for the ceremony. This was followed by student Isabel Shaffer welcoming everyone. Mary Roddy then shared the class vision, and Virginia White explained the reason the class chose green and white to represent it. The student chorus then sang “Over the Summer Sea.” Ethel Creager presented the class motto: “To thine own self be true,” and Nellie Bowers explained why the daisy was the class flower. Gladys Creager then read the class poem, “The Night Brings Out the Stars.”

Isabel Shaffer played an instrumental solo. Kathleen Weddle, Maude Spalding, Dorothy Weller, Updike Cady, Earle Lawyer, Russell Young, Ruth Eyler, and Lillian Baxter performed a playlet titled, “Under Sealed Orders. All the students then sang “Merrily, Merrily Sing.”

Professor Elmer Hoke, head of the Department of Education, Hood College, addressed the class. The diplomas were then presented to the seventh graders.

Class President Edward Foreman and Professor R. X. Day then spoke to the class. Finally, the students sang “Dixieland” and Gertrude Creager gave the valedictory address.

“To use the slang, we believe the crowd was ‘tickled to death’ with this seventh grade class and the program rendered by them,” the Catoctin Clarion reported afterward.

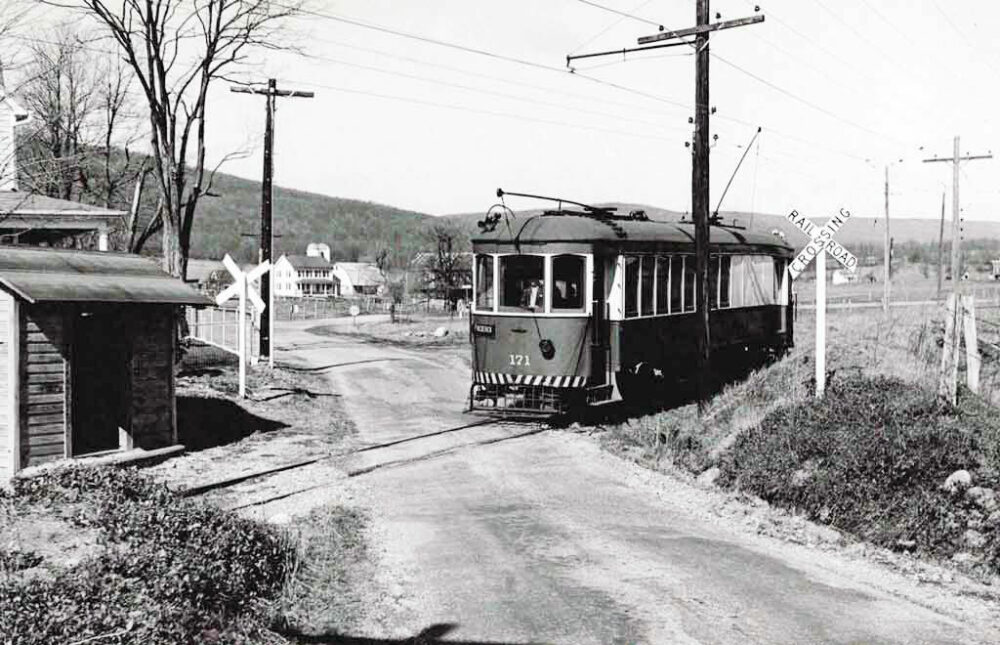

Thurmont High School under construction in 1915.

Photo Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com

Joseph Flautt Frizell was walking along the tracks of the Emmitsburg Railroad one evening in May 1922 with some friends. They were goofing around, as teenage boys are known to do, as they approached the station located on South Seton Avenue.

Joseph Flautt Frizell was walking along the tracks of the Emmitsburg Railroad one evening in May 1922 with some friends. They were goofing around, as teenage boys are known to do, as they approached the station located on South Seton Avenue.