James Rada, Jr.

In the days before air conditioning, Washington D.C. could be nearly unbearable in the summer. Those who could would travel to summer homes in more-agreeable climates. It wasn’t always possible for federal officials, though.

In 1915, some of the towns surrounding the capital city began making their case to serve as the summer capital for the United States, in a similar way to the way President Dwight D. Eisenhower would use his Gettysburg home as a temporary White House while he was recovering from a heart attack. They were generally towns within a couple hours of Washington, D.C., and at a higher elevation.

In August, the Waynesboro Board of Trade appointed a committee to open communications with Congressman D. K. Focht “and urge him to use his influence in having the summer capital located in this section,” according to the Gettysburg Times.

W. H. Doll of the traffic department of the Western Maryland Railway traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with one of President Woodrow Wilson’s secretaries to show the railroad’s support for having Blue Ridge Summit be the summer capital.

“Mr. Doll called attention to the fact that Blue Ridge Summit is now more or less a ‘summer capital’ on account of the large number of government officials and members of the diplomatic corps who spend the heated season there,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

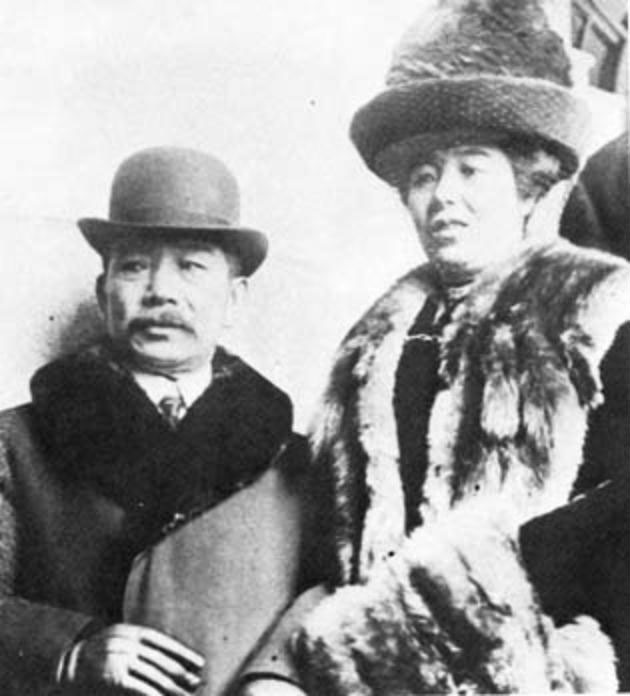

Diplomatic delegations from Argentina, Norway, Japan, and Uruguay already had many of their members spending the summer in Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania. The Washington Post even noted in 1915 that Viscountess Chinda, the wife of Japanese Ambassador Chinda, had traveled to Japanese property in Blue Ridge Summit, calling the summer embassy. The U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Comptroller of the Currency also spent much of the summer in the mountains.

Some of the diplomats and officials had homes, but others simply stayed the summer in the Monterey Inn. The Monterey Inn was probably the most famous of the inns of Blue Ridge Summit. It was built in 1848 and attracted visitors from all over the region. The inn would burn to the ground in 1941, but in 1915, it was the jewel of Blue Ridge Summit.

For a while, it seemed that the government was considering officially designating the town as the summer capital. Engineers from Washington traveled to Blue Ridge Summit in October to take elevations and measurements of the town and surrounding area. Local officials took it as a sign that the government was collecting data on where to build government buildings.

It wasn’t the first time towns had made an appeal to be the summer capital. Earlier in the year, Braddock Heights in Frederick County had made its case only to see nothing come of it. It doesn’t seem that the town fathers made much of persuasive appeal other than offering cooler summer weather within a fairly close location to Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, Virginia Congressman Charles Carlin was making the case for the summer capital being in the Virginia mountains, not far from Washington. The basis of his appeal was that he would submit a bill for designating a summer capital, but only if it was located in his district in Virginia.

Although Blue Ridge Summit’s official recognition as the summer capital failed, the town continued to appeal to foreign delegations. Even as late as 1940, about a dozen foreign embassies maintained summer legations in Blue Ridge, many at Monterey, occasioning it to be called often “the summer capital of the United States,” according to the Living Places webpage for the Monterey Historic District.

Japanese Ambassador Chinda and wife Viscountess Chinda.

Courtesy Photo