by James Rada, Jr.

Note: This is part one of a series about goldfish farming in Frederick County.

Frederick County’s Golden Immigrants

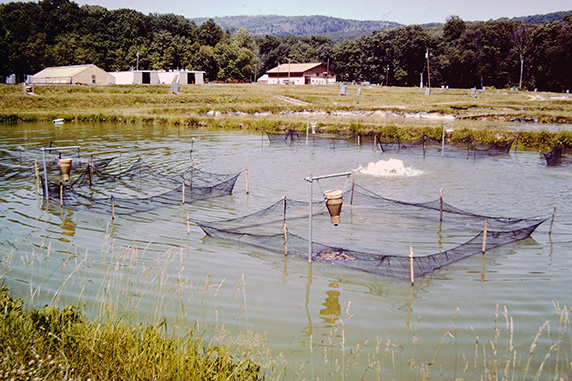

Hunting Creek Fisheries, Courtesy of the Author

History is obscure on how goldfish first came to the United States. The first recorded shipment was in 1878, but the specially bred Oriental fish were swimming in the American ponds and streams before then. Some records indicate it may have been long before then.

When goldfish came to America is uncertain, but one research paper notes: “The only reasonably well-supported record of a foreign fish introduced into this country prior to 1850 is of goldfish.” An article in Fisheries by Leo G. Nico and Pam L. Fuller suggests 1842 as the earliest date and that in 1879 “goldfish could be found in great number in the Hudson River of New York; most specimens were of drab wild colors, but a few could be found that were ‘white, red, and all intermediate conditions.’” Goldfish in 1879 were also sold in New York markets as a food fish, according to National Geographic.

One thing is certain. Once goldfish were in the United States, they found Frederick County, Maryland, to their liking. George Wireman wrote in Gateway to the Mountain that during the first half of the 20th century, Frederick County produced 80 percent of the goldfish in the country.

In 1878, Rear Admiral Daniel Ammens brought a shipment of these beautiful goldfish from Japan to the United States Commission on Fisheries. This is the first recorded entrance of goldfish into the United States.

It is these goldfish that most likely took hold in Frederick County, according to Ernest Tresselt. He was raised on a goldfish farm, Hunting Creek Fisheries in Thurmont, Maryland. He also ran it after his father retired in 1962. His memoirs were titled “Autobiography of a Goldfish Farmer.”

Because of the limited number of native freshwater fish in the United States, the United States Commission of Fisheries (created in 1871) and the Maryland Commission of Fish and Fisheries (created in 1874) introduced European carp into American waters as a supplementary food source for farmers.

Ponds were created for the carp on the grounds of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., and Druid Hill Park in Baltimore. For a shipping fee of two dollars per can, the government would ship carp by rail car and truck all over the country. Once delivered, the empty cans were returned to Washington and Baltimore.

Once Ammens’ goldfish came to the United States, they were kept in ponds near the carp. The goldfish produced so many offspring that they were sold along with the carp to anyone interested in them.

“Since Frederick County, especially the Thurmont area, was settled by Germans who ate a lot of fish, the fish in the area were used up by this time. German families were raised on carp and so many of them purchased carp from the government,” said Tresselt.

Albert Powell, former superintendent of Maryland fish hatcheries, does not mention goldfish in his manuscript, “Historical Information of Maryland’s Commission of Fish and Fisheries with some notes on Game.” This is because goldfish are not considered a game fish, which is the responsibility of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries. Because goldfish are ornamental fish and pets, they are tracked as a crop. Many reports, in fact, call goldfish a crop that was “harvested” in the fall.

A 1921 Catoctin Clarion describes a goldfish harvest this way:

“A sluice gate was slightly raised; at the end of the sluice a large wire basket encloses everything that comes through and a small dip net transfers the fish to buckets, whence they are taken to the sorting room. Here they are emptied about a quart at a time on a table with a sloping galvanized iron top, and as they slide by, four men separate the goldfish from the uncolored goldfish, the tadpoles, crabs, frogs, pond bass, and various other pond inhabitants. The goldfish are put into large floats and afterwards, by the same process above are sorted into their different sizes.”

Powell does, however, note in Historical Information of Maryland’s Commission of Fish and Fisheries with some notes on game that some of the fish introduced in the Druid Hill Park fishponds were golden in color, such as golden tench and orphes. They were among the fish that the fish commissioners began to ship to the public in 1878.

“That’s how goldfish found its way to the Maryland countryside, on the tails of edible carp. It is easy to speculate that one or more farms in Frederick County got goldfish along with their carp during the period when the carp culture in farm fishponds was advocated as a supplementary food supply,” wrote Tresselt.