An Isolated Town Arrives in the 20th Century

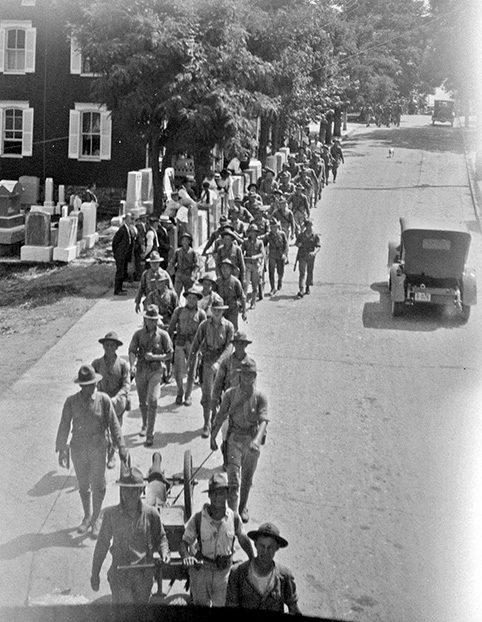

Although Catoctin and South mountains aren’t the largest mountains in America or even the Appalachians, their crooks and crannies provided land where isolated communities sprung up. One of these communities was Friends Creek, west of Emmitsburg in Frederick County.

“Friends creek dashes musically over its rocky bed, dropping frequently into quiet pools, the ideal home of the trout. Close in on each side crowd stern, densely-wooded mountains, forming a pocket, typical of hundreds of similar localities through the entire range of the Appalachian chain,” the Frederick News reported in 1922.

Despite the towns and cities within a reasonable distance from the small community, Friends Creek remained in a bygone era even as the region moved into the 20th century. It was made up of 25 to 30 homes that were not much more than one- to four-room cabins. Each home was filled with large families and multiple dogs.

“The people make a living by tilling little patches of ground cleared off on the less precipitous slopes of the hills and by hunting and fishing. In the summer many of the men go out into the fertile valleys not far away and work on the large farms,” according to the newspaper. “In the winter their chief reliance is on hunting and trapping, and it is whispered that further back in the mountains ‘the moon shines bright upon the moonshine distillery…’”

Few of the residents were literate, and most had such basic math skills that when they dealt with people from the outside world, they needed someone to help them.

“Stubborn in his resistance against what he considers the iconoclasm of modern civilization, standing firmly upon the ways of his forefathers, regardless of their retarding effect upon his own development and comfort, retaining the customs and folklore of past centuries, maintaining an austere and cheerless religion, filled with queer superstitions peculiar to isolated mountain people…,” according to the Frederick News.

But the newspaper noted that by 1922, the modern world had finally started creeping into Friends Creek. Beulah Weldon and Margaret E. Newman were given the credit for easing Friends Creek into the modern world. Weldon was the community’s teacher and Newman was the graduate nurse.

Both of them were also trained social workers associated with the Henry Street Settlement. The Henry Street Settlement was an organization that had formed in 1893 in New York City to provide social services and health care to needy New Yorkers.

However, Weldon and Newman saw that Friends Creek was in need, and they believed they could help.

Newman told the newspaper, “My principal motive in leaving New York and coming here was to help the country children, the native Americans, to get a better share of what is due them. In New York there are fine schools, which are almost swamped by the children of recent immigrants, eager to learn, but remote regions such as this are permitting the children, many of whom are direct descendants of Revolutionary war heroes, to grow up in ignorance. The truth of this terrible proportion of illiteracy among our native-born population was brought home forcibly to men, as to many others, by the revelations of the draft records made during the last war.”

The Frederick County Board of Education supported the women’s efforts. They had built a decent schoolhouse in the community, but they had trouble finding a teacher to work there for any length of time. The Frederick News said the that the reason for this was, “The mountain homes, swarming with children, with no possibility of securing a private room, the meagre and unvaried food and the general isolation did not appeal to young school ma’ams: in fact, no boarding place could be found, and it was not within the power of the Board of Education to furnish a home.”

Even when a teacher could be found for the school, attendance was low. The average attendance was only 8 to 10 pupils, which led to the school being closed intermittently for lack of students.

Newman and Weldon arrived in Friends Creek in the summer of 1919. Newman had learned of the community from her father who had bought land in the area with the plan of planting an orchard. He had often told his daughter he wished something could be done for the people.

The women found a place to live in Friends Creek due to the generosity of Dr. Howard A. Kelly of Baltimore. He bought a rustic home on 53 acres for $300 and allowed the women to live there. They moved in and slowly made improvements to the property over the years when they had time. They also kept a small garden, cows, horse, poultry, sheep and “a flivver,” which is slang for cheap car.

It took time for the community to accept the women, but over three years, they helped the people of Friends Creek make significant problems. Interestingly, the religious leaders were resistant to the changes. The community had two religious groups; Pentecostals or “Holy Rollers” and the “Church of God.”

The Holy Rollers, in particular, were against the changes. The pastor was said to have told his congregation “if the Lord intended them to read and write the Holy Ghost would teach them,” according to the newspapers.

Weldon and Newman persevered.

Weldon started holding school with two classes: those who had attended school and those who hadn’t. At first, the latter class was larger than the former. As the children quickly learned, attendance improved. Eventually, all the children, except those in one or two families were attending school.

Another issue they dealt with was the health of the children. When Weldon and Newman arrived, only 12.5 percent of the children were at a normal weight. The remaining children were underweight. Newman started visiting homes and speaking with the families about nutrition. Since most of the students did not bring a school lunch, the women started a school lunch program.

“As there was no place but the schoolroom to cook the food the distraction was found too great and this was given up, but the teacher and nurse take daily with them to the school a gallon of rich milk from their own cows, which is given to the children who seem to need it most. Few of the families in the settlement own a cow,” the Frederick News reported.

Through diligent efforts, by 1922, 80 percent of the children in the community were at a normal weight.

Weldon and Newman also dealt with problems of poor clothing that was held together by safety pins, snakes, tuberculosis, dental health, and even farming conditions.

It was hard work, but Friends Creek and its residents eventually joined the 20th century.

The original Friends Creek Church of God, built in 1868. It was one of two churches in the Friends Creek community in the early 20th century in Frederick County.