Richard Bard Makes Good His Escape

by James Rada, Jr.

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of columns about Richard Bard’s escape from captivity and the rescue of his wife.

Richard Bard had made his getaway from the Delaware Indians, who had captured his family at their mill near present-day Fairfield on April 13, 1758. He was one of the lucky ones. Two others had been killed by the Indians for no apparent reason. Six other people were still being held prisoner, including his wife.

When the Indians discovered his escape, they searched for Bard, but he hid in a hollow log. Once the Indians had passed him by and were out of hearing range, Bard climbed out and ran off in the other direction.

“He traveled [across] the mountain pick[ing] berries and herbs to survive. His feet and legs were swollen, and his body was in a weak condition. The snow on the brush and leaves of the laurel made it impossible to walk, and he was [compelled] to creep on his hands and knees under the thick brush,” according to L. Dean Calimer in Franklin County Archives VII.

The Indians and their captives remained in the area for a day and night before making their way another twenty miles until they reached an Indian village. There, Catherine Bard, Richard’s wife, was severely beaten by the squaws in the village.

“Now almost exhausted with fatigue she requested leave to remain at this place but was told she might if she preferred being scalped to proceeding,” Archibald Bard, one of Richard and Catherine’s children, wrote in Incidents of Border Life. Instead, the Indians traveled to another village called, Cususkey. Catherine and the others were beaten in this town as well. One man was even killed. “The Indians formed themselves into a circle round the prisoner and commenced by beating him some with sticks and some with tomahawks. He was then tied to a post near a large fire and after being tortured sometimes with burning coals they scalped him and put the scalp on a pole to bleed before his face. A gun barrel was then heated red hot and passed over his body and with a red hot bayonet they pierced his body with many repetitions. In this manner they continued torturing him singing and shouting until he expired,” Archibald wrote.

Meanwhile, Richard was undergoing his own trials to stay alive. The fifth day after his escape, he got some protein in his diet when he killed and ate a rattlesnake.

Eight days after his escape, he found himself in a stream that he would have to wade. On the other side of the river, he found a path that led him to a settlement. He found himself facing three Indians. Instead of being the Delaware Indians who had captured him, they were friendly Cherokee Indians. They escorted Bard to Fort Lyttletown, where he recovered from his experience.

Meanwhile, Catherine’s ordeals went from being physically abused to being adopted as a sister by two Delaware Indians. Catherine was to replace their actual sister, who had died. Over the next few months, Catherine’s new family traveled so much that she became ill and nearly died.

When she did recover, she got a glimpse of what the future might hold for her when she met a woman she knew. “This woman had been in captivity some years and had an Indian husband by whom she had one child,” Archibald wrote. “My mother reproved her for this but received for answer that before she had consented they had tied her to a stake in order to burn her.”

The woman also told her that once captive women learned the Indian language, they either married one of the Delawares or were killed. Knowing this, Catherine played dumb and did not learn the language. She remained as the sister of the braves and was treated kindly.

Once recovered from his ordeal, Richard set out to free his family. He began seeking information about his wife and the Delawares, making many trips from Franklin County to western Pennsylvania, as he followed up on leads. As the weeks turned into years, he despaired at what had happened to his family, but he did not give up.

This determination was what would finally lead to his family being reunited.

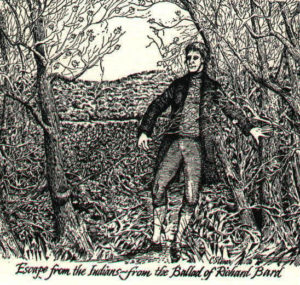

The cover of The Ballad of Richard Bard, a long poem about Bard’s escape from the Indians who captured his family.