Where the White Frogs Frolic

In 1932, Charles Clyde (C.C.) Moler was shopping at Lilypons goldfish nurseries in Frederick County when something in the water caught his eye. The water rippled with activity from the thousands of goldfish in the ponds that been drained to a low level for harvesting. C.C. saw flashes of orange from the goldfish and greenish brown from tadpoles that shared the ponds, but he saw something else, too.

An occasional flash of white caught his eye. He looked closer and saw it was a tadpole. Lilypons raised tadpoles as well as goldfish. Tadpoles acted as scavengers in a goldfish aquarium, eating any food the fish didn’t and helping keep the tank clean.

C.C. pointed out the white tadpoles and had a worker fish them out. He found three. Each one was white with pink eyes. They were albino, a rare congenital defect that causes the loss of any pigmentation.

When asked about an albino frog in the New York Museum of History’s collection at the time, herpetologist Dr. Raymond Ditmars called it, “rarer than human quintuplets.” C.C. had hit a biological lottery jackpot.

“At that time, the museum’s specimen was thought to be the only one in existence and, although widespread publicity brought to light several others, the white frog still holds his rank as one of the rarest forms of albinism,” The Baltimore Sun reported.

Moler surprised Lilypons workers when he told them how rare albino frogs were. They had first noticed albino tadpoles in their ponds the previous year. “No special thought was given to their unusual appearance and, after passing through the regular grading process, a few were shipped out with the normal tadpoles. Several dealers complained that they had received tadpoles which were apparently sick, but no one realized that a rare find had been passed by so casually,” The Baltimore Sun reported.

Moler had Lilypons try to trace the albino tadpoles that had been shipped out. Of the ones they found, “only one had lived to frogdom, and that was dead and resting in alcohol,” according to The Baltimore Sun.

With the news of the rare find, other goldfish farmers in Frederick County started watching the tadpoles they harvested from their ponds. No other ponds yielded the rare albino frogs.

Moler kept the three he found and returned home to Hagerstown. Two of the tadpoles died, but one matured to an albino male bullfrog.

Moler worked as an electrical engineer for Potomac Edison, but caring for the albino frog became his hobby.

He returned to Lilypons the following year during their harvest and found more white tadpoles that he purchased. With a year’s experience, he was better able to care for them. Their tanks were temperature-controlled to be no lower than sixty-five degrees. Moler fed them only live food—primarily earthworms—because frogs won’t eat anything that doesn’t move.

One of these tadpoles matured to a female of the same species as the male.

“Today, they dwell happily together, the world’s first pair of albino frogs, and it is hoped that they will be the Adam and Eve of a new race,” The Baltimore Sun reported.

They were believed to be the only breeding pair of albino bullfrogs in the world.

Experts gave Moler a 50-50 chance of being able to breed them, but he beat the odds, and the Hagerstown Morning Herald reported in 1937 that he had “several hundred Albino tadpoles as a reward.” Of these, he hoped to get as many as 200 to grow to adulthood, but only twenty-three did.

C.C. was so pleased with his success that he presented a pair of albino frogs to the New York Museum of Natural History as a gift. In accepting the gift, Museum Director Dr. G. Kingsley Noble said, “You have already made a very important contribution to science in successfully rearing these delicate creatures.”

The New York Times called Moler, “the world’s only collector and breeder of Albino frogs.”

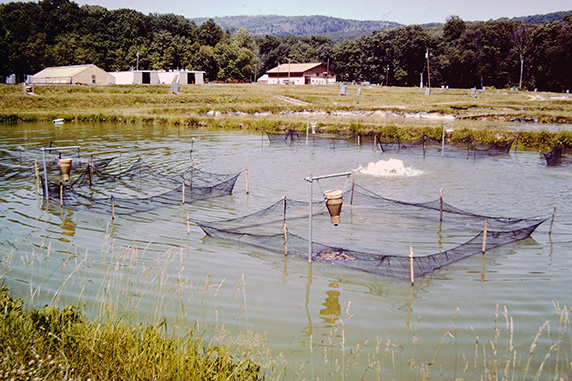

With his collection of albino frogs growing, Moler purchased a farm near Wagner’s Crossroad on Beaver Creek, along the new Dual Highway. He had three screened outdoor pools built on the property. He then purchased three abandoned Hagerstown and Frederick Railway trolley cars and placed one next to each pool.

C.C. converted one trolley into a massive heated aquarium, where the tadpoles could stay in the winter. Other tadpoles were left in the pools, where they disappeared into the mud at the bottom. Moler wanted to see if the albino frogs could survive the winter as well as regular frogs.

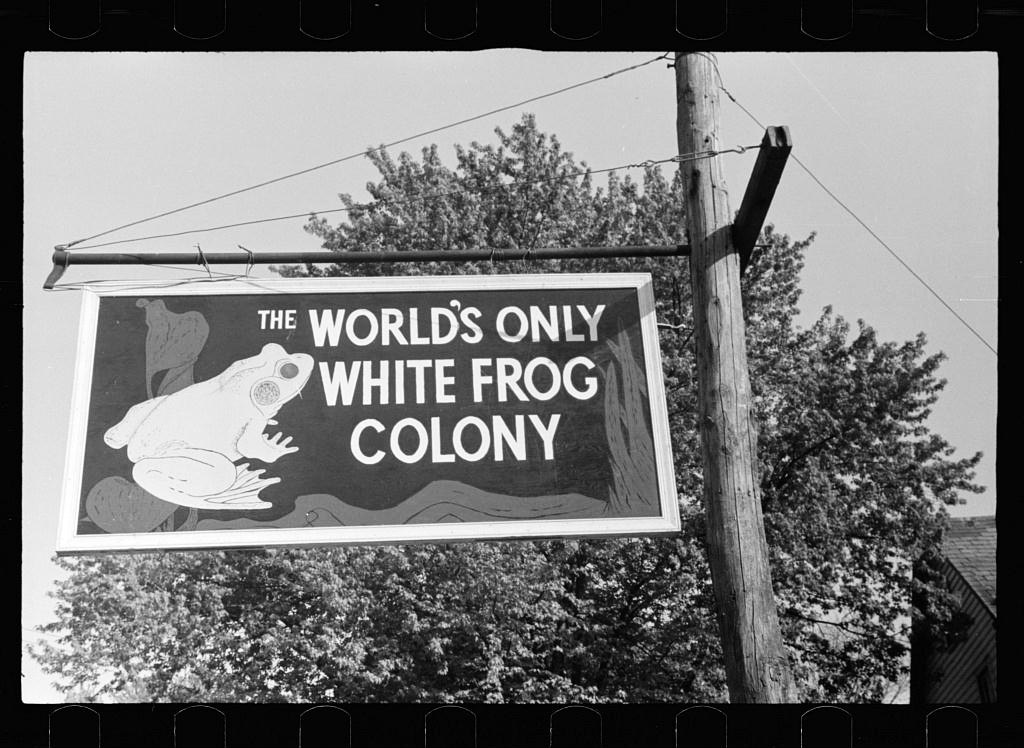

The farm soon became a tourist attraction, advertising itself as having the only white frog colony in the world.

The sign in front of C. C. Moler’s white frog farm.

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress