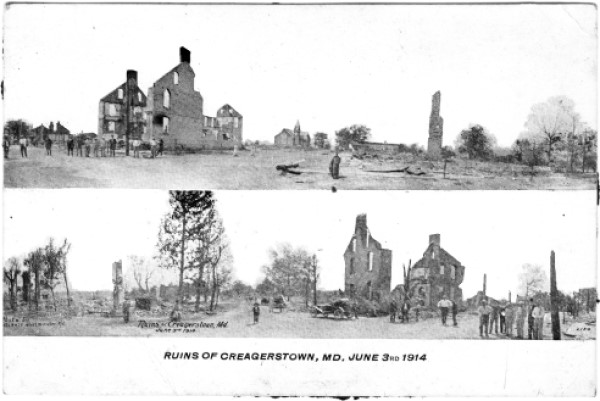

Ira H. Buhrman

“Lost at Sea”

by Richard D. L. Fulton

Ira Harrison Buhrman was born on November 10, 1887, in Foxville (Frederick County), to parents Harvey Meade Buhrman, a farmer, and Theresa Need Buhrman. Buhrman had eight brothers and sisters (two apparently having died at birth).

Buhrman resided in Foxville until his death and was, at one point, employed as a laborer in a local lumber mill.

The (Frederick) News reported on February 10, 1942, that Buhrman had enlisted in the United States Marine Corps in July 1918, and served one enlistment in Hawaii. The newspaper reported that he became a member of the 13th Regiment, which was then employed in Europe as part of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

He subsequently was attached to Company D of the 15th Separate Battalion until the signing of the Armistice in November 1918. Buhrman remained with the Marine Corps at Marine Base Quantico until discharged. It was reported that, after having been discharged from the Marine Corps, he was involved in the construction of Camp Ritchie (perhaps due to his former employment in the lumber industry).

The (Frederick) News also reported that Buhrman was an award-winning marksman, having been awarded a number of medals for sharpshooting and marksmanship while serving in the Marine Corps.

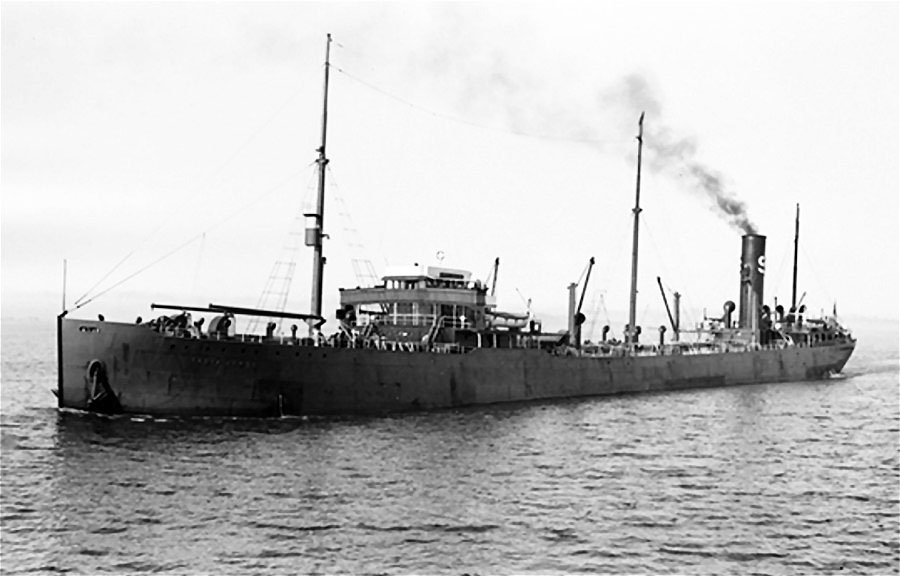

By the time World War II broke out, Buhrman, at 53 years of age, was too old to serve, so he opted to sign up with the Merchant Marines (officially known as the United States Merchant Navy), and, thus, on October 8, 1941, ended up as a member of the crew of the fuel tanker India Arrow, owned by the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company.

He served as a ship’s wiper, which entailed cleaning the engine compartment and machinery, as well as other jobs that were assigned by the ship’s engineers.

On February 4, 1942, the India Arrow was making its way from Corpus Christi, Texas, to Carteret, New Jersey, with a load of 88,369 gallons of diesel fuel. The ship was unarmed and unescorted.

The India Arrow was struck by a torpedo fired by a German submarine (subsequently identified as the German submarine U-103) when the tanker was only about 20 miles southeast of Cape May. Russpickett.com reported that the German submarine “then surfaced and fired seven shells from her deck gun (at the stricken tanker) at two-minute intervals, from a distance of 250 yards into the bow section, which remained above water as the stern was sinking.”

The Frederick Post reported on February 11, 1942, that Buhrman may have been in the engine room when the tanker was hit by the torpedo ”just aft of the engine room,” further noting that only two or three of the occupants in the engine room had escaped that portion of the ship. Buhrman was initially listed as missing.

The vast majority of officers and the crew of the India Arrow had actually survived the attack, except for two that were killed outright, when the submarine shelled the ship. However, 18 of the officers and crew drowned when their lifeboat sank. Ultimately, as the result, eight officers and twenty of the crew were lost in the attack on the India Arrow, while only one officer and eleven of the crew survived.

Between January and August in 1942, German submarines sank more than a dozen ships off the New Jersey Coast, and even more off the coasts of other Mid-Atlantic states, according to whyy.org.

The (Frederick) News reported that Buhrman was the first Frederick County resident to have been killed in World War II. He was posthumously awarded the Merchant Marine Medal and the Combat Bar with Star. The Combat Bar was awarded to Merchant Marines who were onboard a ship that was attacked by an enemy. A star was added if the recipient was also forced to abandon the ship (or was killed in the attack).

Buhrman was a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars as the result of his service during WWI. According to wikitree.com, in the wake of his mother’s death in 1947, “his name was added to her headstone in Mount Bethel Cemetery in Garfield as a memorial, since his remains were never recovered.

Ira H. Buhrman Source: findagrave.com and Wings Across America

India Arrow

Source: City of Little Rock, LR Parks & Recreation

Anyone who might know a Veteran or is a Veteran, who would like to share their experiences in the military for publication in The Catoctin Banner, is invited to contact the columnist at richardfulton@earthlink.net. Thank you.

Upon Combs’ death from congestive heart failure (according to The Washington Post) at age 92, his memorial service was held at the Myers-Durboraw Funeral Home in Emmitsburg. He was interred in the Emmitsburg Memorial Cemetery.