Edwin C. Creeger, Jr.

Namesake of Legion Post 168

by Richard D. L. Fulton

Edwin C. Creeger, Jr. was born on August 21, 1920, in Thurmont to parents Edwin C. and Ethel Creeger. He was his parents’ only child.

The family’s address was given as having been 7 North Church Street, Thurmont. Creeger’s father owned and operated the Creeger Motor Company in Thurmont, and he had served in France during the First World War.

Creeger graduated from Thurmont High School in 1937 and from the Lebanon Valley College in 1941.

According to an article published on October 27, 1943, by The (Frederick) News, Creeger “had always been especially talented along musical lines and after having majored in this subject, became music supervisor at the Lower Paxton High School, Harrisburg.”

At a Thurmont High School Alumni Banquet held on June 1, 1942, Creeger sang “Johnny Doughboy Found a Rose in Ireland” and “River Stay ‘Way from My Door,” accompanied by a pianist, as part of the entertainment held during the banquet.

He was still employed at the Lower Paxton High School when he was granted a leave of absence to enlist in the Navy.

Creeger enlisted at 21 years of age on July 7, 1942, in the Naval Reserve. Upon enlistment, he was listed as having been 5’ 9” in height, weighing 180 pounds, having gray eyes, brown hair, and a ruddy completion.

He initially received training at Marietta College in Ohio (World War II had briefly turned the Marietta College into a pilot training center, according to the Marietta Times).

He then received additional training at the Davis and Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia, and at the Naval facility on the University of Georgia campus in Athens, Georgia. That training was followed by additional training in Hollywood, Florida, probably at the Naval Training School there.

Having completed his training, he graduated as a navigator on June 23, 1942, in Hollywood, Florida.

Ensign Creeger had been on sea duty since September 10, 1943, according to The (Frederick) News, which further noted that he “had spent a two-week leave with his parents before leaving for service on September 20.”

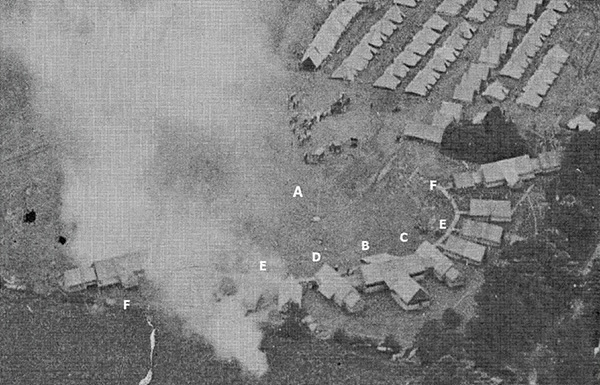

Nearly a month following his visitation leave with his parents, Creeger met his death on October 23, 1943, when his plane was shot down at Dunkeswell, East Devon District, Devon, England, deeming him almost certainly as a casualty of the Battle of the Atlantic, said to be the longest, continuous military campaign in World War II.

The (Hagerstown) Daily Mail reported on October 28, 1943, that Creeger had been killed “in the performance of his duty and in the service of his country,” further reporting on November 10, 1943, that, “The Naval officer was killed in the crash of a seaplane, presumably somewhere in England, the Navy Department announcement said.”

His body was interred in the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial, Coton, South Cambridgeshire District, Cambridgeshire, England.

The (Frederick) News, announced in their November 17, 1945, issue that a new American Legion Post was being formed in Thurmont and would be named the Edwin C. Creeger Jr. Post 168, in honor of the fallen aviator.

The (Frederick) News further reported on December 1, 1945, that “The father of the Thurmont youth who lost his life in World War II, and after whom the new post of Legion is named, was elected Commander of the Thurmont organization.”

Creeger was a member of St. John’s Lutheran Church in Thurmont.

On August 21, 1944, Creeger’s family published a Card of Thanks in The (Frederick) News, which read, “To our very good neighbors and wonderful friends of Edwin, Jr., and ourselves, we wish to thank each and every one from the bottom of our hearts, for the many wonderful words and acts of consolation in our very dark hour of sorrow… His Mother and Father.”

Edwin C Creeger, Jr.