Pennsylvania’s State Fossil

Richard D. L. Fulton

Some 350 million years ago, “Frog Eyes” plowed through the mud and silt on the floor of an ancient sea that had then covered much of the area that would someday become the State of Pennsylvania.

Based upon the discovery of the fossilized gut contents of a related creature that once foraged the sea bottom in the Czech Republic, “Frog Eyes” likely sought out such morsels of food such as that provided by the presence of small, nearly microscopic, crustaceans. It’s likely that small soft-bodied sea creatures were on “Frog Eyes”’ menu as well.

While “Frog Eyes” became extinct some 300 million years ago, the creature’s “legacy” lives on as Pennsylvania’s state fossil… sort of.

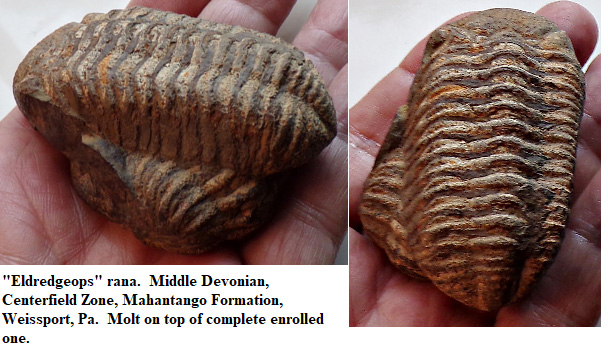

Specifically, “Frog Eyes” was a sea creature presently known as a trilobite (derived from the fact that the shell, or carapace, of these animals was divided into three sections or lobes). Scientifically, “Frog Eyes” was given the name Phacops rana in 1832 by paleontologist Jacob Green.

Phacops rana literally translates into “frog eyes,” rana being Latin for frog, while phacops is Greek for lenses (referring to the eyes, which were comprised of many lenses, like that of a bee’s).

The fossils of Phacops rana are plentiful in Pennsylvania, where they lived during a period of time known as the Middle Devonian, the rocks of which in Pennsylvania are comprised of layers of dark shale and siltstones. Adults can range in size from about 3.5 inches to 5 inches.

Phacops rana was designated as being the state fossil of Pennsylvania by an act of the state General Assembly of the Commonwealth on December 5, 1988, a decree which stated, “Fossils of Phacops rana are found in many parts of Pennsylvania, and, therefore, the Phacops rana is selected, designated and adopted as the official State fossil of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania…”

Seems straight forward enough, right? Maryland thought so back in 1984, when the Maryland General Assembly designated a prehistoric snail, Ecphora quadricostata, as the state fossil. Three years later, it was discovered they had designated the incorrect species of Ecphora as their state fossil, resulting in the state General Assembly having to redesignate the proper species, Ecphora gardnerae, as being the state fossil.

Presently, Pennsylvania’s state fossil is faced with the same enigma. Since Phacops rana was designated as Pennsylvania’s state fossil, it was subsequently discovered that the species is not even a member of the genus Phacops, but instead is a member of the genus Eldredgeops, which was named for paleontologist, Niles Eldredge.

Apparently, Phacops only occurred in Africa during the Devonian Period, and Eldredgeops is the proper generic name for the species that lived in the oceans that covered the Americas. As a result, Pennsylvania’s state fossil, Phacops rana then became known as Eldredgeops rana, which also resulted in the old name of “Frog Eyes” then becoming “Eldredge’s Frog.”

The name change reportedly occurred in the 1990s, when paleontologists evaluated the genus Phacops and Eldredgeops.

Apparently, Pennsylvania’s General Assembly didn’t get the memo. Unlike Maryland, the name change has yet to be reflected by the Pennsylvania General Assembly, and the erroneous name, Phacops rana, is still indicated as being the current state fossil on Pennsylvania’s Department of Conservation & Natural Resources website.

If the reader might be interested in trying to find a specimen or so of Pennsylvania’s state fossil, a couple of references might prove to be of assistance in the quest (neither are in print, but both can be found online): Fossil collecting in Pennsylvania by Donald M. Hoskins, Jon D. Inners, and John A. Harper (the writer of ‘Frog Eyes’ – Pennsylvania’s State Fossil served as a consultant for this book, as indicated in the acknowledgments), and Stratigraphy and Paleontology of the Mahantango Formation in South-Central Pennsylvania by R. L. Ellison.

The emblem on the backs of these plates, depicting crossed hammers and a crown, dates them between 1918 and 1939. This fine porcelain was first produced in Pirkenhammer, Bohemia, in 1803. During the 1830s, it was considered the best dining ware made and was very popular with royalty throughout Europe. In 1915, a beautiful floral pattern, gilded in gold with a navy background, was created for Pope Benedict XV. Searches of this particular pattern, numbered “4812,” yielded little, but a similar, older pattern was priced at $41.00 per plate on a popular bidding site. Expect this porcelain to value over time, but currently a reasonable price would be $20 to $30 per plate.

The emblem on the backs of these plates, depicting crossed hammers and a crown, dates them between 1918 and 1939. This fine porcelain was first produced in Pirkenhammer, Bohemia, in 1803. During the 1830s, it was considered the best dining ware made and was very popular with royalty throughout Europe. In 1915, a beautiful floral pattern, gilded in gold with a navy background, was created for Pope Benedict XV. Searches of this particular pattern, numbered “4812,” yielded little, but a similar, older pattern was priced at $41.00 per plate on a popular bidding site. Expect this porcelain to value over time, but currently a reasonable price would be $20 to $30 per plate. Your scale appears to be composed of metal with an iron base. It appears to have all but one of its weights. The original “bowl” that would’ve fit on the exposed four prongs is missing. A search of late 19th century English and European scales revealed two with handles and a swirl design on the bases, similar to yours, but there were no identifying marks. The photo of the “WB” etched on your scale suggests that it could be a WB Scott scale, which was a manufacturer in the USA at the turn of the last century. However, none of the Scott scales resemble this piece. The scale was most likely used in a store for candy, jewelry, or hardware items. Although it’s very fancy for a “general store,” it might have been used to weigh sacks of seeds. Your scale is in excellent condition. Based on its age and design, expect to get $175 to $250.

Your scale appears to be composed of metal with an iron base. It appears to have all but one of its weights. The original “bowl” that would’ve fit on the exposed four prongs is missing. A search of late 19th century English and European scales revealed two with handles and a swirl design on the bases, similar to yours, but there were no identifying marks. The photo of the “WB” etched on your scale suggests that it could be a WB Scott scale, which was a manufacturer in the USA at the turn of the last century. However, none of the Scott scales resemble this piece. The scale was most likely used in a store for candy, jewelry, or hardware items. Although it’s very fancy for a “general store,” it might have been used to weigh sacks of seeds. Your scale is in excellent condition. Based on its age and design, expect to get $175 to $250.