The Year is…1953

by James Rada, Jr.

Being a Good Neighbor on Catoctin Mountain

It’s nice to have good neighbors. It’s even nicer when the neighbor is the President of the United States.

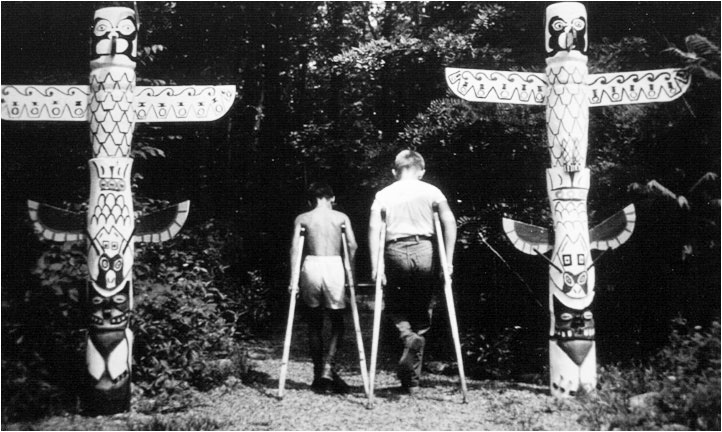

Works Progress Administration laborers built the 22 camp buildings at Camp Greentop between 1934 and 1938. The log buildings were a mix of sleeping cabins, administrative buildings, and lodges. The plan was for Camp Greentop to look the same as Camp Misty Mount, but it was changed during construction so that the League for Crippled Children in Baltimore could use the buildings. According to the National Park Service, the camp was one of the first handicap-accessible facilities in the country.

Although the camp was built to house 150 children, 94 children—53 girls and 41 boys (ages 7 to 15)—were enjoying the outdoors there in June 1953. Most of them suffered from cerebral palsy or polio. On the morning of June 28, their neighbors, Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower, came to visit.

“Responding to an invitation sent to him by some of the children, the President turned up at the camp about 9:30 a.m.,” the Frederick News reported. “The children had not been told that Eisenhower and the first lady were coming, and they cut loose with squeals of delight as their distinguished guests drove up.”

The first couple had been staying at Camp David, the presidential retreat near Camp Greentop on Catoctin Mountain, and were on their way back to Washington, D.C.

The Eisenhowers spent a half-hour at the camp, meeting and talking with the children. Although the visit surprised the children, they gathered and sung a couple of songs for the Eisenhowers.

“Do you know what the President did this morning?” Mamie asked one little girl. “He got up and made hotcakes.”

One boy said to the President, “Hello, President Eisenhower, I saw you on television.”

Eisenhower chuckled and replied. “You ought to be looking at Gary Cooper on television.”

As the visit wound down, Eisenhower looked around for his wife, who had been led away by a group of children. “I think I’d better go and get my little gal,” he told the group of children near him.

He located Mamie and helped her into the car, but before they left, the President found Fred Volland, the camp business manager. He asked what the children’s favorite dessert was. Then he slipped Volland some money and said with a grin, “Give them the dessert on me.”

From Catoctin Mountain, the couple continued on to Washington, D.C.

Camp Greentop Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1989.

Photograph shows a pair of campers at Camp Greentop in 1937.