The Eisenhower Farm Story

Richard D. L. Fulton

Dwight ”Ike” D. Eisenhower was born on October 14, in Denison, Texas, the son of David D. and Elizabeth Eisenhower (the spelling of Eisenhower was changed from its original spelling of Eisenhauer, which had been the last name of his great-grandfather).

Eisenhower married Mary “Mamie” in 1914 and would remain with her until his death at the Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, DC, in 1968. The couple had two sons: Doud “Ikky” Dwight Eisenhower (1917-1921) and John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower (1922-2013).

Eisenhower is probably best known as the World War II commander of the Allied forces in Europe, and as the two-term president of the United States from 1953 to 1961.

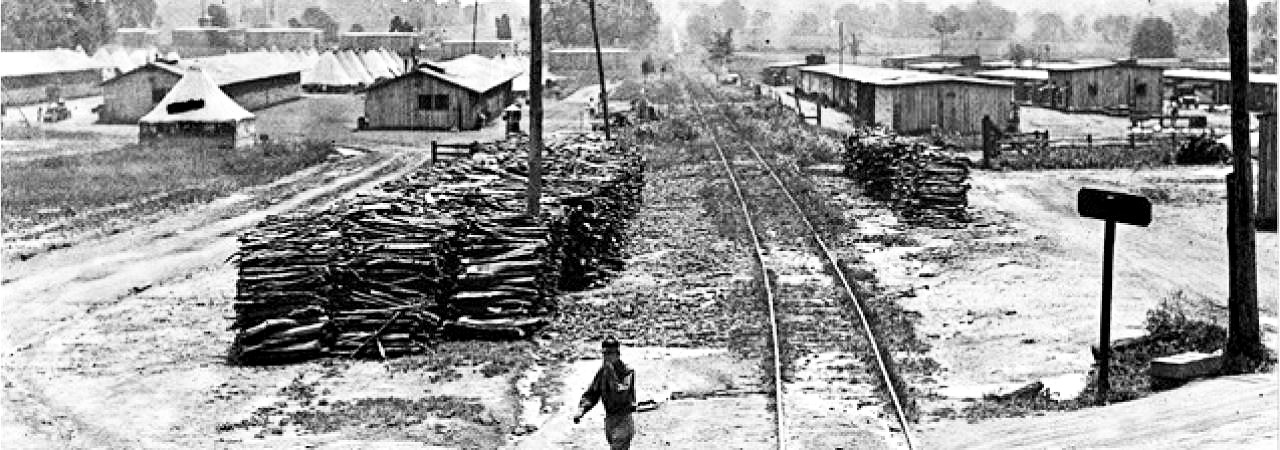

He may be somewhat lesser known for his command of Camp Colt, a training ground for the United States Army’s first armored tank crews, which sprawled in and around the Gettysburg battlefield in 1918—40 years before he and his wife would see and find a permanent home in Cumberland Township, just outside of the Gettysburg Borough (see “Gettysburg’s Camp Colt Birthplace of American Armor,” by Richard D. L. Fulton, January 2024 Catoctin Banner).

Regardless of the farm’s actual geographic location, it was generally always referred to as Eisenhower’s Gettysburg farm, and/or Eisenhower’s Gettysburg home.

Buying the farm was actually the idea of Eisenhower’s wife, Mamie. In a story written, entitled “Mamie Eisenhower Says Gettysburg is Her Home,” by the Associated Press staff, and published in the September 5, 1952, edition of The Gettysburg Times, she (Mamie Eisenhower) stated in an interview that “buying the house (farm) was her idea.”

The writer of the article stated that she said, “when she told her husband she liked that place, he had replied, ‘OK, go ahead and buy it’.”

Apparently, it did not require a lot of persistence for his wife to convince him to purchase the property. The Gettysburg Times stated in their November 20, 1950, edition, “The General was a frequent visitor… and has expressed a sentimental as well as a patriotic attachment to the Gettysburg region,” and later noted in a 1952 story that the general had (recently) stated, “I hope to rock out my last days on a comfortable porch here (in Gettysburg).”

The farm in question had been, prior to its sale to the Eisenhowers, known as the Redding Farm, owned by Allen Redding and his wife. The farm consisted of some 189 acres (also reported as 179 acres, and then again, as 188 acres), and the Eisenhowers had paid $40,000 for the farm, according to The Gettysburg Times.

The Reddings had purchased the farm from Mary Alice Hemler, wife of the deceased George Hemler, in 1934, during the Great Depression, for $15,000.

The Times reported on November 20, 1950, “Attorney Richard A. Brown said that he and John C. Bream, real estate dealer, had closed the deal (with the Eisenhowers) on November 1. And he had described the farm as a dairy farm “located on the road (Pumping Station Road) leading to the Gettysburg water works, adjoining West Confederate Avenue.” The old driveway still exists but is posted for National Park staff use only. Tourists now access the farm from Old Emmitsburg Road.

The farmhouse itself was described as a nine-room brick house. Mamie Eisenhower told the Associated Press, “Some of my friends are trying to persuade me to build a new place on one of the (farm’s) hills, but I fell in love with the old house first,” adding, “The house is mine and I love it. and all the trees around it.”

As to its proposed furnishing, she stated, “I can hardly wait to get my hands on that house and fix it up.” In response to someone suggesting that she should furnish it in Early American style, she had responded, “No, Early Eisenhower. We have picked things up wherever we have lived, and we (already) have furniture from all over the world.”

An article published in the January 1, 1951, issue of The Gettysburg Times, entitled “General ‘Ike’ goes to Europe,” noted that, according to a condition of sale, the Reddings would be permitted to remain on the farm until April 2, 1951,” adding, “It seems likely the General and Mrs. Eisenhower will eventually take up residence on the Redding farm.”

Additionally, The Times article noted that business in Europe had required the general’s attendance, to which his wife was not necessarily pleased, as it had postponed the move-in date to the farmhouse. She told the press she was disappointed at not going to the farm, that she thought she and the general were “old enough now to settle down.”

By November 1952, the Eisenhowers had still not relocated their primary residence to the farm. The Eisenhowers’ property manager (retired Brigadier General Arthur S. Nevins, one of Eisenhower’s war-time staff officers) had described the condition of the farmhouse to The Gettysburg Times as “being in need of ‘considerable work’… before it could qualify as a presidential residence.”

In fact, after having been elected as president, and while living in the White House, the old farmhouse they would be calling “home” proved as having been a larger challenge than they had envisioned.

According to the National Park Service, “Once Dwight and Mamie were in the White House, it was discovered that most of their Gettysburg home was in dire straits due to its advanced age and the deteriorating condition of the wooden interior,” further noting that the Eisenhowers were advised “to raze the home to the ground and start fresh. However, Mrs. Eisenhower wished to save as much of the original home as possible, so she implemented a new plan that saved a portion of the 1800s structure.”

Presently, the effort to save that which could be saved is reflected in what tourists may see today. “That part of the home today contains the kitchen and butler’s pantry downstairs and the maid’s room upstairs. The older brick section has a rougher exterior appearance from the newer brick and is easily visible from outside the house. Because the older and newer bricks did not match, the house was painted white.” Construction began in the spring of 1953 and was finished in the spring of 1955.

During Eisenhower’s two terms, the home was primarily used as a presidential retreat, and for meeting with and entertaining various world leaders. After leaving the White House at the end of the president’s second term, the Eisenhowers were finally able to move into their farmhouse in January 1961. The Gettysburg Times reported on January 12, 1961, “When the Eisenhowers come here on Friday (they actually didn’t arrive until January 20), they will go to their farm to rest after an arduous last day in the White House.”

On January 21, a reception and dinner were held at the Hotel Gettysburg. A “welcome home” rostrum was erected at the Town Square for general public reception, accompanied by music and a “brief welcome address,” The Times reported.

On that same morning, Eisenhower met with Oren H. Wilson, president of the board of trustees of the Gettysburg Presbyterian Church, to discuss matters relating to the local church. At the conclusion of their meeting, Eisenhower stepped outside, along with Wilson, and found himself confronted by reporters and photographers.

The Times reported that Eisenhower had asked the group why the people were still so interested in him. One reporter replied, because “We still like you.”

Following Eisenhower’s demise in 1969, the former president was laid to rest on the grounds of the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas.

Former First Lady Mamie Eisenhower died in 1979, and was buried next to her husband.

As an aside, the Eisenhower property continued to function as an operating farm, primarily as a dairy farm, during the duration of their ownership. But, that alone, is yet another story…

For additional information, visit the National Park Service’s Eisenhower National Historic Site website at nps.gov/eise.

Dwight D. Eisenhower and wife Mamie at their Gettysburg farm home.

British General Bernard Montgomery and Dwight D. Eisenhower touring the Gettysburg Battlefield in 1957.