Medic John W. Bennett

Survived Being KIA

by Richard D. L. Fulton

John W. Bennett was born (“at home”) on March 13, 1948, in Takoma Park, a Montgomery County suburb of Washington, D.C., to parents J.W. and Elmira Bennett. He graduated from Westminster High School.

Bennett subsequently met his wife Shirley (“on a blind date”). They have two children: John, Jr. and Diana, and they have lived in Fairfield for more than three decades. His wife is presently employed at Saint Catherine’s Nursing Center in Emmitsburg.

Bennett enlisted in the Army and was inducted in October 1966, as a conscientious objector, and thus served as a medic. As a private, Bennett was sent to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for training, and subsequently to Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

After graduating from training, Bennett was sent to Hawaii, where he was assigned to the United States Army’s 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, 11th Light Infantry Brigade, to undergo “jungle training” to prepare for deployment to Vietnam.

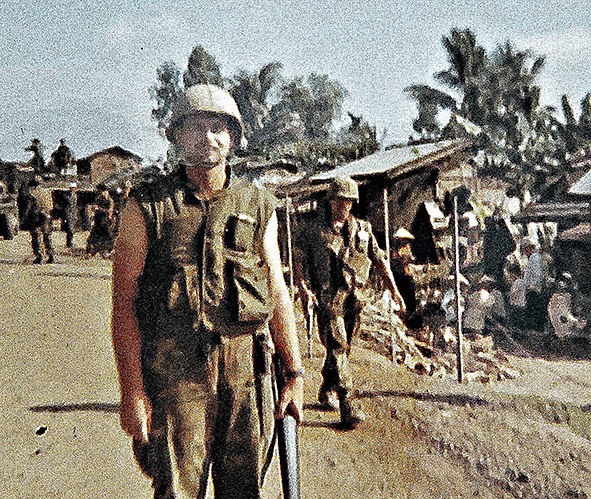

Bennett and his unit departed from Hawaii on December 5, 1967, and after a 10-day trek across the ocean, the 11th Light Infantry Brigade was “boots-on-the-ground” in Vietnam, ultimately arriving at Due Pho.

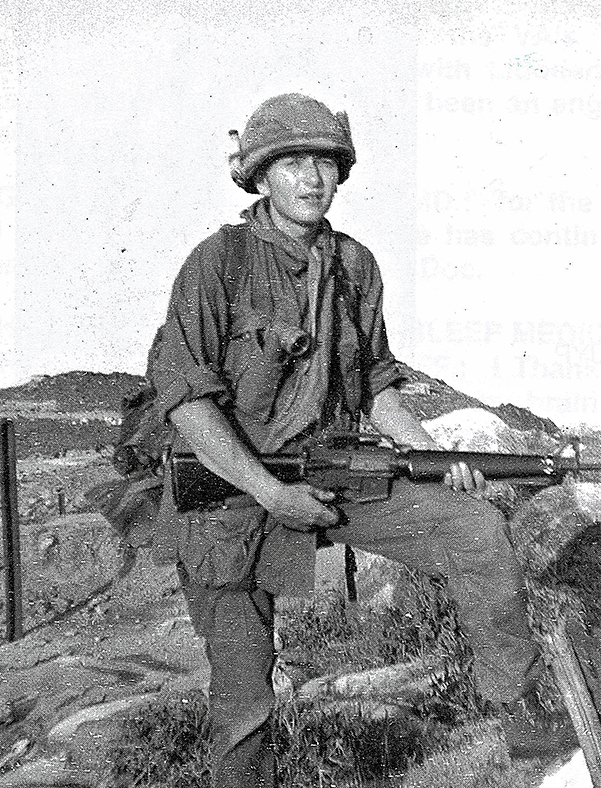

Within days, he found himself assigned to a Recon (Reconnaissance) unit as part of Echo Company, wherein he saw numerous actions in operations against the Vietnamese.

On one mission, in particular, his Recon unit was suddenly ambushed in a surprise attack, which ultimately turned into a full-scale battle as the Recon team fell back to a safer position. Before the engagement was concluded, the enemy troops found themselves being hit with air strikes, artillery rounds, mortar and gunship fire, and even a coastal warship that had opened up on the enemy.

Bennett said, “Perhaps a million dollars’ worth of ammunition was fired that night… As I looked around the field (after the fight), I could see literally hundreds of bodies.”

But it was during Operation Dragon when the unit’s position came under regular attacks, particularly during storms. Bennett said the enemy preferred moving through the jungles during storms because it made it more difficult for the American defenders to see them.

Having been attacked during a storm the preceding night, Bennett instinctively grabbed an M-16 and several rounds of ammunition and settled down next to a bunker, where he had a clear view of an adjacent hill (medics can carry arms if a unit is short-handed and/or if a troop position is under imminent threat).

Being seated by the bunker was the last thing Bennett remembered, except for a moment when he thought he was lying on a litter next to a helicopter, at which point he said, “Then there was a huge tunnel (that he saw) and pastel-colored lights with a really bright light at the end, and then suddenly, it went out and left me in the dark.”

Some 10 to 20 hours later, he regained consciousness but felt that he was confined in some kind of plastic tarp. Reaching down into his pocket, he found his knife and cut his way out.

When he sat up, he was startled to discover the tarp in which he had been encased was actually a body bag, and “around me were perhaps a hundred litters with filled body bags on them.” After sitting there for some 20 minutes, a medical staff member entered into what turned out as being a military morgue, and attended to Bennett, showing him his bag-tag that stated, “KIA – Struck by Lightning.”

Amazingly, after recuperating, Bennett returned to duty.

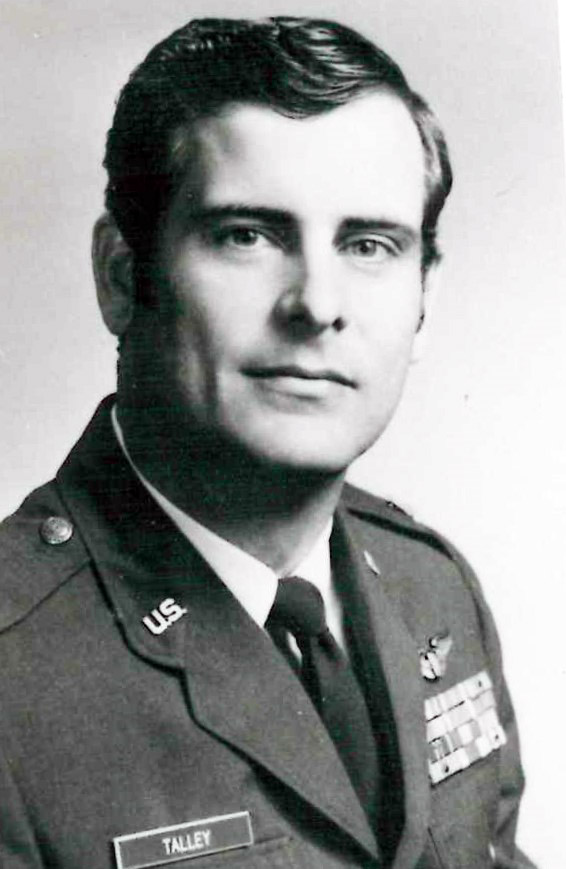

Bennett was honorably discharged from the Army in October 1972. He was awarded two Bronze Stars and numerous other awards issued by the Republic of Vietnam and the United States Army. He was never issued a Purple Heart. He did write a book on his personal experiences during the war, entitled Killed in Action – Struck by Lightning, published by the United Book Press, Baltimore.

To this day, Bennett stated that he still suffers from the effects of having been struck by lightning.