Richard D. L. Fulton

Residents of the Emmitsburg area were probably not shocked at reading the news regarding the great blizzard of March 1-2, 1914, that “Emmitsburg was in the midst of the severest portion of the storm…”

But, in fact, the destruction was ultimately countywide, so much so, that the March 3 The (Frederick) News reported that only the Walkersville, Libertytown, Woodsboro, and Ladiesburg had sustained “very limited damage to speak of.”

The News reported on March 2, “Frederick and the county were visited by one of the worst storms last night and today in the history of this section,” adding, “fierce northwest winds up to 60 miles per hour were prevalent throughout the night and into the following morning, noting that the wind howled with a fierceness which was probably never known before in this part of the county.”

Temperatures were reported to have reached a high of 23 degrees during the day and attained a low of 11 degrees at night, not including wind chill factors.

The blizzard virtually impacted the greater upper Mid-Atlantic. The News stated in their March 3 edition that 15 lives were lost in New York, and five lives were lost in Philadelphia due to the snow and wind, and that the railroads were “badly crippled.”

In Frederick County, authorities began to assess the damage after the storm subsided post-morning on March 2. The News reported on March 3 that the degree of damage estimated to have occurred on the day of the storm “exceeds any estimate that was yesterday given.”

Emmitsburg, the newspaper reported, “was cut off from telephone communications with Frederick” during much of the height of the storm, noting that “houses were unroofed and four or five barns were blown down.”

Additionally, the roof of the Emmitsburg High School was blown off and a gable was “blown in,” the newspaper noted, adding that plastering had been badly cracked and that “it is felt the walls have been rendered unsafe.”

Other area educational institutions damaged were the Cattail Branch Run School, which had a gable driven-in and the roof torn off, and the school house at Brenman’s was nearly a “total loss.”

Two hotels were damaged in Emmitsburg, including the Hotel Spangler and the Hotel Hinddinger, mostly in the form of windows having been blown in. In addition to widespread chimney damage and the loss of portions of slate roofs in town, the roof was also torn off the Emmitsburg Broom Factory, according to The News.

In Thurmont, a portion of the roof of the United Brethren Church was lost, and the end of the high school was blown in, according to the March 3 edition of The Baltimore Sun, which further noted that when the school’s wall was blown in, the bricks “crashed through the floors to the basement, demolishing desks and twisting part of the structure…”

The Baltimore Sun also reported that the Thurmont Town Hall and (a grain?) elevator were damaged, as well as various other structures and out-buildings, and that a barn was also destroyed, killing a number of the livestock.

Countywide, some 100 barns were destroyed in the blizzard, along with the deaths of dozens of livestock. In total, more than 136 structures were damaged, according to the March 4 issue of The News, amounting to an estimated $200,000 in damages. The newspaper reported there were some impacted communities that had not as yet reported their losses.

Amazingly, there were few deaths, some estimates ranging from one to three.

No figures were published in the newspapers regarding the depth of the snowfall, but the average received by the Upper Mid-Atlantic was two feet or more of snow.

Most of the damage appeared to have been caused by the persistent high-wind velocities.

The old Emmitsburg hotel, known as the Spangler Hotel in 1914, weathered out the

blizzard, sustaining damage mainly to the windows.

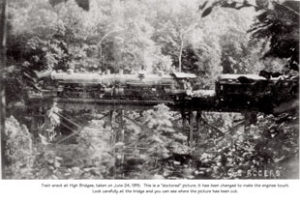

On June 25, 1915, the Blue Mountain Express, bound for Hagerstown, crashed head-on with a mail train traveling east from Hagerstown, crumpling the two engines and sending a baggage car off the bridge, where the crash occurred, and into the ravine below.

On June 25, 1915, the Blue Mountain Express, bound for Hagerstown, crashed head-on with a mail train traveling east from Hagerstown, crumpling the two engines and sending a baggage car off the bridge, where the crash occurred, and into the ravine below.