Richard D. L. Fulton

There was a time in history when the country was laced with short-line railroads. In fact, almost all of the early railroads were short-line railroads, until many were absorbed through consolidation with larger railroads, years later.

Most short-line railroads were created to serve limited purposes, as dictated by local economies. Many also dabbled in providing passenger service, but overall, that effort was never really all that successful.

While it may seem that “short-line railroads” would take the name from the length of the railroads, the truth is that size varied widely. Their main distinguishing characteristic is that they served principally to deliver local goods to a connection with a larger railroad system/company.

The Emmitsburg Railroad serves as a prime example of a short-line railroad in all respects, in its length, and in its purpose.

The Rise of the Road

The Emmitsburg Railroad was granted its incorporation by an act of the Maryland Assembly on March 28, 1868, according to Emmitsburg Railroad, by W. R. Hicks (published by the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society).

According to Hicks, the incorporators were Daniel George Adelsberger, Joseph Brawner, Joshua Walter, E. S. Taney, Joseph Byers, Dr. Andrew Annan, Isaac Hyder, George W. Rowe, Dr. James W. Bichelberger, Sr., Christian Zacharies, and Michael Adelsberger.

However, it would be three years before the actual work commenced for bringing the proposed railroad into existence, and without the aid of the Sisters of Charity of Saint Joseph’s College, the railroad might never have actually been constructed.

The Sisters of Charity of Saint Joseph’s College became involved in making the much sought-after railroad a reality with loans (the Sisters of Charity contributed more than half the capital needed to build the railroad, thereby, deeming them the majority bondholders) and rights-of-way (across Saint Joseph’s land).

The (Hagerstown) Daily Mail reported on February 20, 1940, when the Western Maryland Railroad constructed its line in the wake of the Civil War, it bypassed Emmitsburg by seven miles. The Sisters of Charity of Saint Joseph’s “decided to do something about that.”

Groundbreaking for the Emmitsburg Railroad was held on the morning of March 25,1871, at Rocky Ridge (sometimes referred to as Emmitsburg Junction)—the proposed final destination of the railroad (where it would connect with the Western Maryland Railroad).

The groundbreaking was attended by Emmitsburg Railroad President Joseph Motter and directors, representatives of the Western Maryland Railroad, and representatives of Saint Joseph’s College, as well as other guests.

The Catoctin Clarion concluded its April 1, 1871, report of the festivities, that when the first pick struck up the dirt at the commencement of the groundbreaking, “there came forth rocks and sand and reddish earth—and the birth of the Emmitsburg Railroad was announced,” and concluded with, “so the railroad (the peremptory work) passes into history. So, lookout for the locomotive!”

A second celebration took place on November 22, 1875, when the railroad was officially opened for business.

The Baltimore Sun reported on November 23 that exactly when the railroad would be officially running was not released to the public until Saturday, November 20, that the decision to commence operations on the 22nd was made public.

Further, it was noted that the Emmitsburg Railroad would be offering free rides to the public on that day. The Sun reported that “the news spread through the town like wildfire, and nearly everybody, old and young, took advantage of this opportunity.” As a result, hundreds of riders were transported back and forth from Emmitsburg to Rocky Ridge that day, according to the Sun.

The town adults, the newspaper noted, tended to regard the completion of the railroad as “the beginning of a new era for Emmitsburg.”

Assorted Misadventures

November 28, 1908, didn’t start off with a bang, but it could have very nearly ended in one.

The Catoctin Clarion reported in their January 28, 1909, issue, “The Emmitsburg Railroad pleaded guilty in the United States District Court, in Baltimore, Tuesday, of transporting dynamite on a passenger train.” The Catoctin Clarion attributed their story to The Baltimore Sun.

The plea was entered after the United States Grand Jury had indicted the company the same morning. The guilty plea was submitted by the company attorney.

District Attorney John C. Rose told the newspaper that the Emmitsburg Railroad’s rolling stock “is very limited. It has no freight cars,” and all the freight is loaded into a combine. He said the train during the incident consisted of the engine, a tender, a combination baggage and smoking car, and a passenger car.

The district attorney reported that six packages of dynamite were loaded into the baggage and smoking car at Rocky Ridge for delivery to Emmitsburg, and this was done by the baggage master without the knowledge of the other railroad officials.

The railroad was fined $100 (the equivalent of $3,611.46 in today’s money).

Then, there was the Great Emmitsburg Locomotive Chase, in which one of the steam engines bound for Rocky Ridge lost it brakes and was slow crawling its way towards the junction. Apparently, the journey was slow enough to allow one of the train crew to jump and run to a home or business and call Emmitsburg to report the problem.

A second train was dispatched from Emmitsburg to try and intercept the runaway steam engine, and couple onto it to break it, before it reached the end-of-the-line… literally.

The effort paid off, and the crippled engine was hauled back to the Emmitsburg shop for brakes.

The End of the Line

Only 26 years after the groundbreaking, the little railroad was in financial trouble.

The Gettysburg Times reported on February 10, 1940, that on January 15, the directors of the Emmitsburg Railroad called for a vote among the existing stockholders to dissolve and abandon the Emmitsburg Railroad. Out of some 1,000 votes, the motion was defeated by a mere 29 “no” votes.

The short-line was then sold into receivership “to a syndicate” and reorganized, according to the (Hagerstown) Daily Mail. Even then, by the mid-1930s, so little passenger traffic utilized the line that the State Public Service Commission restricted the railroad to handling freight only.

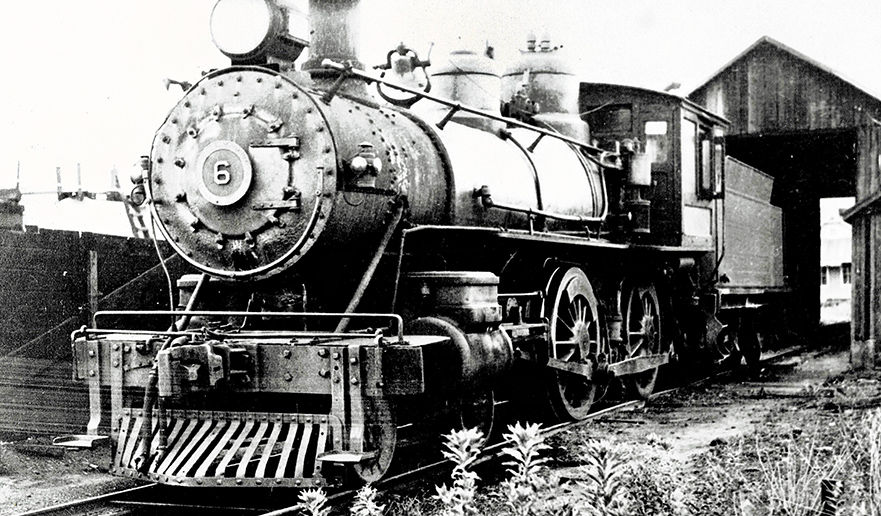

The Gettysburg Times reported on November 4, 1940, “The locomotive of the now-defunct Emmitsburg Railroad steamed out of town last Saturday morning, probably never to return.” The engine was sold to the Salzberg Company, New York. This was probably Engine No. 8, which the (Hagerstown) Daily Mail was referring to when it stated on February 20, 1940, “But old (Emmitsburg) No. 8, the company’s last engine, hasn’t even turned a wheel since the motor truck took over in July (1939).”

*Author’s note: This story is barely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the history of the Emmitsburg Railroad. Highly recommended, in spite of a few errors, a good starting place would be to read Emmitsburg Railroad, by W. R. Hicks, published by the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society.

Emmitsburg Railroad Company steam engine No. 6; From the collection of Eileen Catherine Curtis; Used with permission.

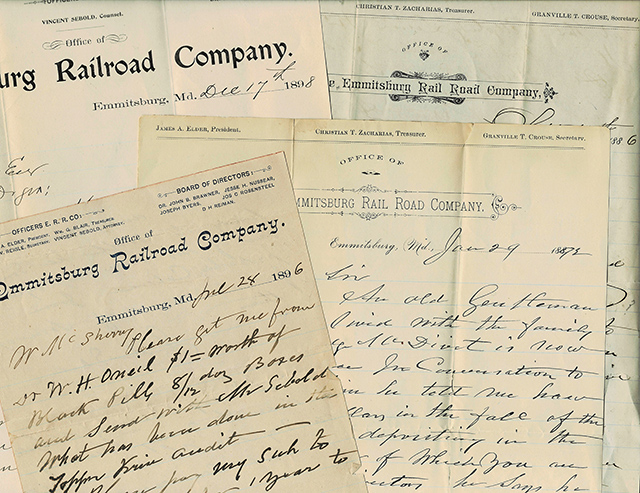

Documents of the Emmitsburg Railroad Company, 1886, 1892, 1896, 1898; From the collection of Eileen Catherine Curtis; Used with permission.