by Richard D. L. Fulton

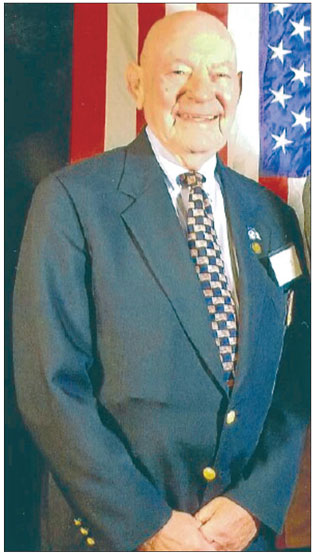

Major George W. Webb

Gettysburg’s “Tuskegee Airman”

When George W. Webb, then-holding the rank of first lieutenant, reported for duty as the first black commander of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp on the Gettysburg battlefield, the only red tails he would have encountered there would have been the species of hawks that flew overhead.

The irony of that was, as World War II broke out, “red tails” would come to assume a whole new meaning in his life.

First Lieutenant Webb secured his Army commission as the result of ROTC training he had received at Howard University, having graduated in 1926. In May 1939 he was assigned to be a member of the staff at the CCC camp in McMillan Woods on the Gettysburg Battlefield.

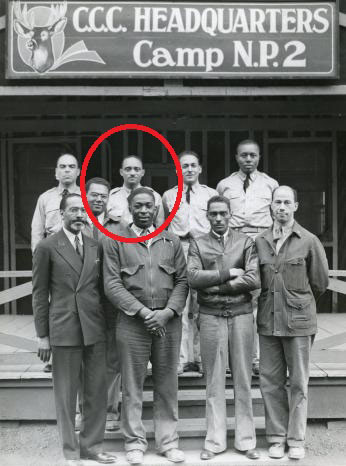

The CCC had established two camps on the Gettysburg Battlefield. The first camp was located in 1933 in Pitzer Woods (in the field behind where the General Longstreet monument stands today) and designated NP-1, and the second camp was located in McMillan Woods in 1934 on the western slope of Seminary Ridge, taking its access off West Confederate Avenue, and designated NP-2.

The CCC camp in Pitzer Woods was comprised of all-black recruits under the command of all white officers as NP-2 had been, except that during late 1939, two years after the Pitzer Woods camp had been abandoned, it was announced that the NP-2 was to become the first all-black (recruits and officers) in the country. At the time, the all-black staff assumed command, the McMillan Woods camp served as home to 198 CCC program “enrollees (designated as being the 135th Company).”

Lieutenant Webb assumed command of the NP-2 on November 12, 1939, when the camp was about to begin being led by an all-black command structure. Although Webb was described as a “native Washingtonian.” Beginning with his assignment to the NP-2, he afterwards always regarded Gettysburg as his home (before being sent to Gettysburg, Webb had served as supervisor of the Industrial Home School of Blue Plains in Washington, D.C.).

Webb received an official send-off at the NP-2 on August 25, 1941, in the form of a “smoker and banquet.” The Gettysburg Times noted that, under Webb’s command, the camp had a superior rating “as one of the most outstanding companies in the central district.”

On August 19, the lieutenant arrived at Chanute Field, Illinois, to commence with his training to serve as the adjutant officer of the 99th Pursuit Squadron (also known as the Red Tails, due to their having painted their airplane tails red. The group was not referred to as the Tuskegee Airmen until it appeared in a book in 1955). The Black Dispatch reported at that time that Webb was married and had three children (two girls and one boy).

During the second week of September 1941, he was dispatched to the Tuskegee (Alabama) Institute, where he officially assumed his assignment as adjutant of the 99th Pursuit Squadron at what would become Tuskegee Army Airfield.

By January 1942, Adjutant Lieutenant Webb had been appointed provost marshal at the Tuskegee flying school, becoming the first black provost marshal in the United States Army (although he continued in training for that position for six months at the Provost Marshal General School in Fort Custer, Michigan through August 13, 1943). He was additionally appointed as fire marshal and transportation officer.

As an aside, in October 1942, the flying school opened its brand-new chapel, Webb’s youngest son was the first child baptized in the new facility.

By February 20, 1943, he had also assumed the command of the military police unit at the Tuskegee flying school and had been promoted to captain. In September 1943, Webb had been promoted to major, just days after having completed his provost marshal training in Fort Custer. His wife had also given birth to a third daughter.

The Tuskegee Army Air Field closed in 1947; 932 pilots had been successfully graduated from the program. Among these, 66 Tuskegee airmen died in combat.