by Priscilla Rall

The mission of the “Silent Service” is to “Seek, Find, and Destroy.”

Raymond Lloyd, from near Ladiesburg, lived that mission during WWII. He started in humble beginnings, born in Hanover, Pennsylvania, to Raymond and Mary Catherine Neller Lloyd in 1921. He was the oldest of three children. His father was a machinist, but during the Great Depression, he found little work. Mary Catherine slaved at a clothing manufacturing plant, sometimes returning home in tears as the work was so hard. The family ate a lot of hominy and mush. Raymond was often sent to the store with an empty jar to get filled with dark molasses for five cents rather than the six-cents lighter variety. Sometimes, the family lacked the money to pay the electric bill and their power was cut off. They made money nipping green beans for the canning factory. They would get several large bags of beans and sit in the yard, nipping off the ends. Mary Catherine bought lots of oatmeal, as the boxes had dishes in the bottom and she prized those. In those days, Hanover had no sewage system and everyone had outhouses! There were no buses to take students to school. So, when the snow was deep, Raymond’s mother wrapped newspaper around his legs and tied them in place with twine. To help his family, young Raymond helped deliver milk, getting up at 2:30 a.m. to put the milk jars on porches and collect the empties. He also had a newspaper route in the afternoon, riding his bicycle around town. Raymond graduated from high school in 1939 and first started working with his father in a machine shop. Then, Raymond went to York, Pennsylvania, to a munitions plant, making 20-mm guns, working 7 days a week, 10 to 12 hours a day.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor immediately changed the United States. Raymond was upset about it, as were all Americans. He decided to join the U.S. Navy, although his parents were not too happy about his decision. He went to Baltimore and enlisted for six years. After six weeks of basic training, Raymond volunteered for the submarine service. His first test was to hold his breath for two minutes. After passing that test, he was sent to New London, Connecticut, where a psychiatrist examined him. After that, Raymond was tested to see if he could endure 52 pounds of pressure. Then it was off to a huge water tank, 100-feet deep. To pass, one had to be able to go up 100 feet without going too fast and getting the bends. Passing that difficult test, he was off to sub-school and became Seaman 2nd Class. After a number of boring assignments, he finally was assigned to a submarine, the USS Gunnel, which was just back from North Africa and led by Captain McCain, the father of the late Senator John McCain. It held 72 enlisted men and 7 officers. Lloyd’s job was to man the periscope shears and look out for anything in the air or sea and report immediately to the captain. After three days, the Gunnel left for war patrol. His parents knew nothing about his assignment or even the name of the submarine.

The Gunnel left New London and went south through the Panama Canal, then on to Pearl Harbor, and finally to Midway Island. Lloyd’s position had him high in the air, and if the captain ordered the boat to dive, he had 15 seconds to get down the hatch before it was closed. The Gunnel was sent to the Yellow Sea and Tokyo Bay. Their mission: to seek, find, and destroy any and all enemy shipping. Once Raymond sighted a camouflaged Japanese plane flying low, and he gave the warning. Raymond got through the hatch in time and the boat dove. Then, they heard a number of depth charges go off. The sub escaped unharmed. Another time, the boat’s sonar picked up a signal, and Lloyd saw a light on the horizon. He reported this to the captain, who fired three torpedoes. One hit and exploded, but the other two didn’t explode. The Navy was plagued with defective Mark 14 torpedoes, which they blamed on the captains’ errors. At least two subs were destroyed by their own torpedoes, which made a U-turn and sunk the American subs. Captain McCain then fired two more torpedoes, but only one exploded. The Japanese freighter started sinking as its crew began firing at the Gunnel.

Later, the Gunnel picked up two heavily loaded ships on radar, riding low in the water, plus three destroyer escorts. From the surface, the Gunnel fired four torpedoes, running according to the captain, “hot, straight, and normal.” Then, someone yelled, “Oh my God, they are leaving a smokescreen.” The Gunnel started to dive as the torpedo hit the freighter, and it exploded. The enemy destroyers started dropping depth charges, and the diving officer told the captain, “We’re in trouble.” The sub submerged to 300 feet, as depth charges exploded on both sides of the boat. They knocked out the lighting system, and the Gunnel starting springing leaks. Lloyd said that they stayed submerged for “hours and hours,” as the captain ordered “silent running.” They had almost used up their battery power and oxygen when the captain ordered her to surface. Lloyd immediately climbed the periscope shears and sighted two enemy ships, and he fired two torpedoes “shot right down the throat.” One ship exploded into pieces as the Gunnel submerged. This turned into a harrowing time for the Gunnel’s crew as they could hear what sounded like grappling hooks sliding over the Gunnel, trying to grab her and bring her to the surface. They stayed submerged for two days. The temperature in the boat was 120 degrees, the emergency oxygen was about empty, and they had just enough battery power to get to the surface. Cpt. McCain called a meeting of all the crew. “We have two choices: we can surface, then flood the ship and take our chances that we’ll be rescued, or we can surface with our battle crew ready and all guns on deck.” With one voice the crew answered, “We’ll fight it out!” So, they surfaced, ready to do battle…but the seas were empty! A heavy fog concealed their position, and they slowly crept away back to Midway.

After a 30-day pass home, Raymond returned to the Gunnel, and they left port, going south of Tokyo Bay. One night, they picked up a target and moved in. Firing torpedoes, they hit and sunk the enemy ship, but suddenly there was a destroyer heading straight for the Gunnel. Diving quickly, they counted 30-depth charges as they took to “silent running.” After things got quiet, they went to the surface and found another target, a high-masted trawler; it could be a trap. As Lloyd was on the periscope shear, he saw strange bubbles coming straight towards the Gunnel. “My God, it’s a torpedo… My God it’s another!” McCain immediately shouted, “All ahead flank rudder.” The crew watched as the torpedoes went past them, only feet away from the sub. Much later, Lloyd was given credit for saving the crew and the sub with his sharp eyes.

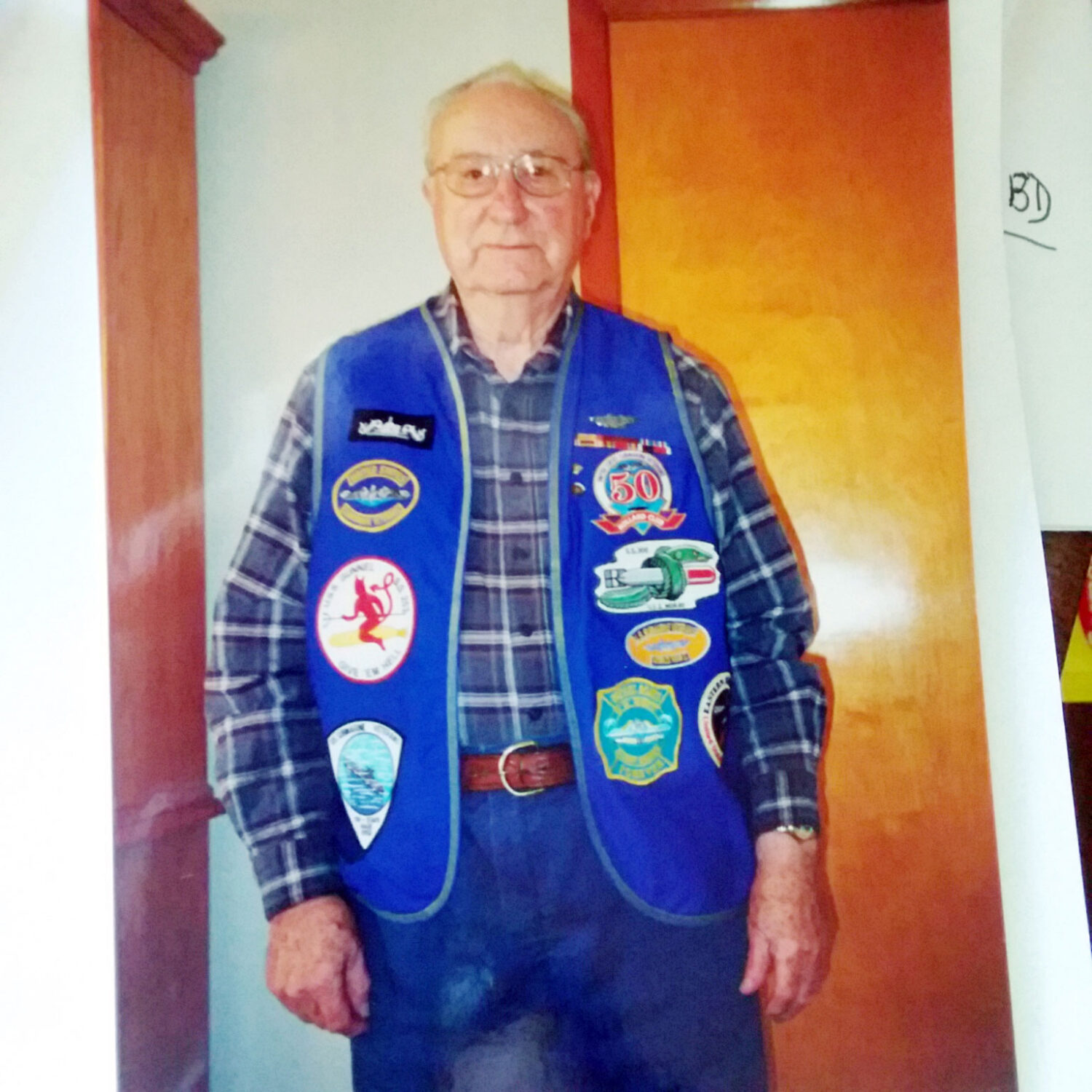

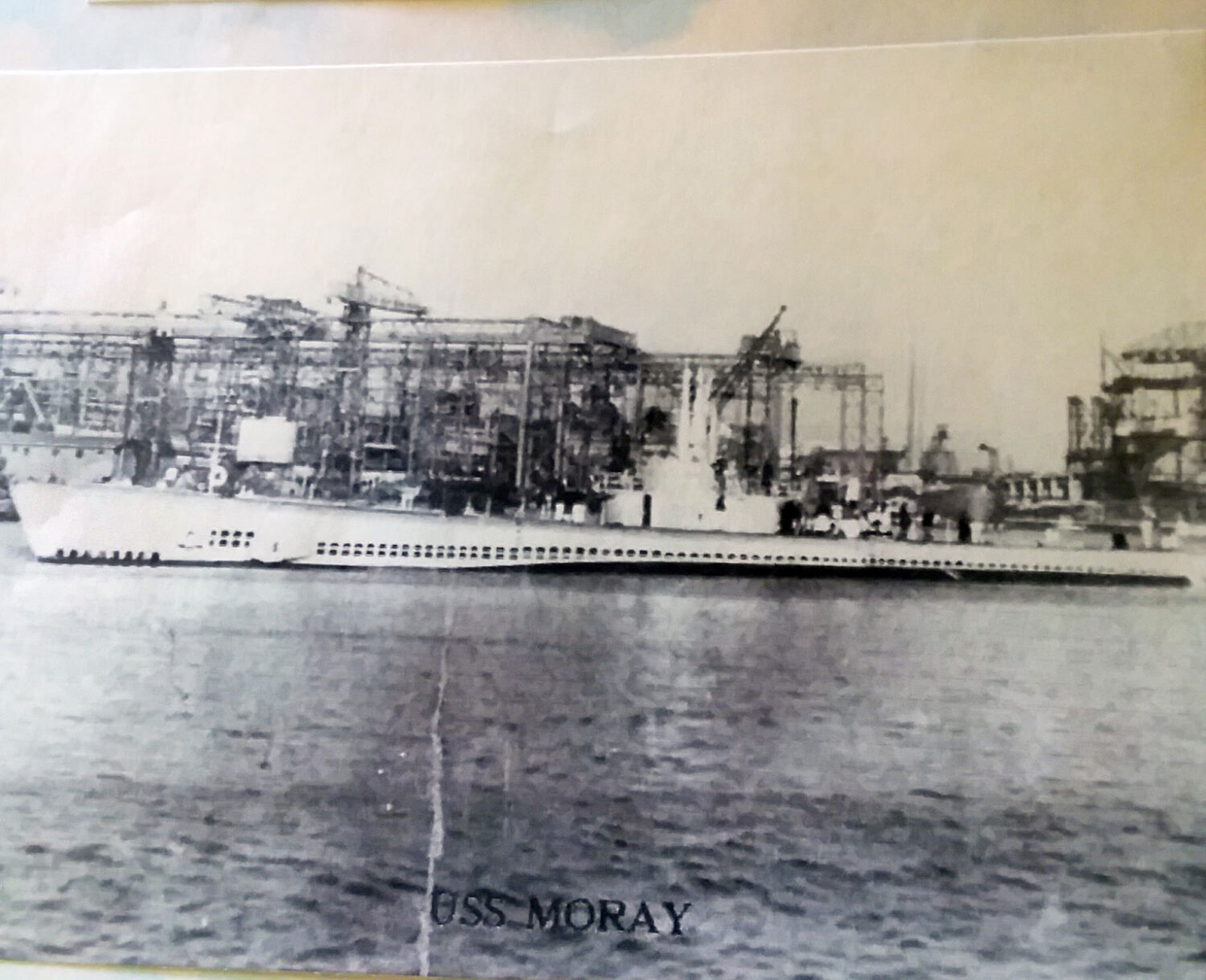

Lloyd was now Yeoman 1st Class, and he spent five months on Midway, keeping track of crew members and doing office work. What he remembers most is the gooney birds, or albatrosses, on the island. His next assignment was in San Francisco, censoring letters. He was then sent to Philadelphia for sub maintenance on the USS Moray, which was getting ready to be commissioned. When she was ready, Raymond sailed on her, again through the Panama Canal and on to Saipan, where they were put on lifeguard duty, picking up any airplane crew that had gone down. But, then they located a target, fired two torpedoes, and hit dead on. The freighter exploded in a ball of fire!

Then, it was back to Midway to keep a lane clear for the scheduled invasion of Japan. The atom bombs made that unnecessary, and Raymond was finally cleared to go home, except for a pesky x-ray that revealed that he had T.B. He then spent 11 months in a Navy hospital before it cleared up. His son, Jim, was born while he was in the hospital. Tragically, his first wife developed multiple sclerosis and soon passed away.

Back home, Raymond decided he wanted to go to college. First, he went to Gettysburg College and then to Johns Hopkins. Eventually, he began work as the assistant commissioner, Division of Labor and Industry, retiring after 16 years. He married Evelyn in 1953, and they moved into a home they built near Ladiesburg.

Raymond certainly followed the mission of the submarine corps to seek, find, and destroy. Few Americans know how much the submarines did to win the war in the Pacific. Fifty-two submarines were lost and 3,600 sailors did not survive. Out of four submariners, only three returned home. Remember the Silent Service when you celebrate our victory in WWII. They certainly deserve our praise.

Courtesy Photos

Raymond Lloyd

The USS Gunnel

Insignia for the USS Moray