A Local Arrest Leads to National Death Penalty Case

by James Rada, Jr.

An arrest in Thurmont in 1949 was the first domino to tip in Merlin James Leiby’s life that led to him being executed for murder in Florida a few years later in a case that drew national coverage.

Leiby was like a cat with nine lives. Despite a long record of run-ins with the law, nothing seemed to stick. He escaped without consequences. However, eventually, a cat’s lives run out, and so did Leiby’s.

After a series of robberies at O’Toole’s Garage in Thurmont, police arrested Leiby. The police investigation also identified the Frederick barber as the leading suspect in other robberies throughout the county. A February grand jury named him in several indictments.

He was released on bond, but then he failed to appear in circuit court in March. His bail bondsman, Glenn Crum, was required to pay the court the $1,500 bail amount (about $20,000 in today’s dollars).

Police then arrested Leiby in Florida, where he had fled after making bail. The arrest wasn’t for his outstanding warrant in Frederick County, though. He was now a suspect in the murder of a Baltimore pharmacist in Jacksonville, Florida. “The seriousness of the charge in Florida left some doubt here as to whether Leiby will ever be returned to Frederick County as a fugitive,” the Emmitsburg Chronicle reported.

Detective Inspector H. V. Branch of Jacksonville told local police that Leiby had admitted killing Leonard Applebaum, a 27-year-old Baltimore pharmacist, on the Tamiami Trail, about 72 miles from Miami. Applebaum’s body was found under a bridge over a dry creek. He had been shot six times, and news reports frequently called it his “bullet-riddled body.”

“Branch said Leiby told officers he won an automobile and a large sum of money from Applebaum in a gambling game at Tampa,” the Emmitsburg Chronicle reported. “In an argument later, the confession disclosed, Leiby said he shot Applebaum in self-defense.”

According to Leiby, he said he won $1,300 from Applebaum, who admitted he couldn’t pay because he only had $200 on him. He said he had friends in New Orleans who would help him. He asked Leiby to drive with him to the city to get the money. Leiby agreed. They started on the journey, but Applebaum stopped in the middle of nowhere, pulled a gun on Leiby, and said he would not pay. Leiby drew his own weapon and shot Applebaum.

When police stopped Leiby, police also found the murder weapon inside. Leiby later admitted that after shooting Applebaum, he drove the body from Tampa to the place where he disposed of it.

Interestingly, Leiby said that he and Applebaum hadn’t known each other in Maryland.

Applebaum was a Navy veteran who had been in Florida on vacation but had been missing from his Miami Beach hotel since March 11. Police started questioning Leiby because his girlfriend had gotten suspicious when he showed up with a lot more money than she had seen him with prior.

As an aside, Helen Leiby, Merlin Leiby’s wife, filed for divorce on the grounds of adultery while Leiby was being held on murder charges in Florida. The couple had married in Frederick in August 1948. She discovered his infidelity when the newspapers mentioned his girlfriend in Florida. She was granted her divorce in October.

In late April 1949, it appeared that Leiby still had some of his feline lives when it was announced that his trial was stalled because of “failure of officers to fix the scene of the fatal shooting,” according to the Frederick Post. This is because although Leiby admitted to the murder, he couldn’t say where along the trail it happened. It caused confusion over what court had jurisdiction over the case.

He was finally indicted on May 26.

Then, in mid-July, came the surprising news that his indictment had been thrown out on technical grounds. “Circuit Judge Lynn Gerald ruled the indictment invalid because the grand jury which returned it was drawn by a court clerk instead of a judge,” the Frederick News reported. This required a new grand jury to be empaneled.

On July 21, prosecutors in Florida used an old state law that had never been used before to allow officials in Collier County to prosecute the case. “The law permits a defendant to be tried in any county through which the transient has passed. In order to avoid conflicting constitutional provisions requiring murder cases to be tried in the county in which the crime was committed,” Washington Evening Star reported.

With both the jurisdictional and jury issues settled, the case moved forward, but the four-day trial did not happen until March 1950.

The jury took only 40 minutes to deliberate and find Leiby guilty of first-degree murder.

“The defense presented no evidence in arguing the case to the jury. [Defense Attorney] Smith asserted the State had not proved the crime was planned or that it had occurred in this (Collier) county,” the Frederick News reported.

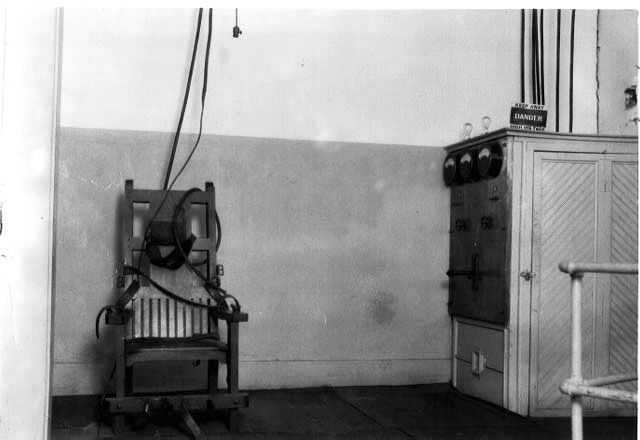

Leiby was sentenced to die in the electric chair. It was Collier County’s first and only death penalty case.

As Leiby sat in jail awaiting execution, he filed appeal after appeal. Although none were successful, it delayed the execution. At one point, the governor of Florida considered clemency, but the Florida Parole Commission opposed it, in part, because Leiby had outstanding warrants in both Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Finally, at the end of 1951, his execution was set for some time during the second week of January 1952. The exact date was left to the prison conducting the execution.

Leiby’s luck stepped in once again, and on January 7, 1952, Gov. Fuller Warren recalled his death warrant, temporarily.

It seemed Leiby had material evidence in another case. He said he had heard two convicted rapists plotting an escape that had ended in the death of one of them and the other one wounded. The NAACP wanted the county sheriff punished because the wounded rapist was saying he had been shot without reason. The courts wanted to hear Leiby’s testimony before deciding whether action needed to be taken against the sheriff.

Finally, on June 30, 1952, Leiby was led to the electric chair. He had no final words before his luck ran out, and he was executed.