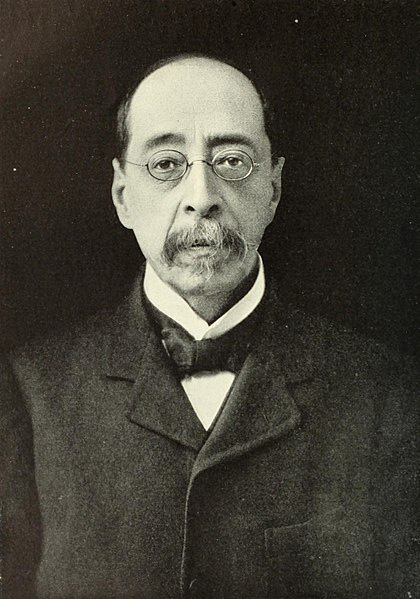

John Lafarge Helped Expand the Art World

by James Rada, Jr.

The Statue of Liberty was introduced to her husband by a Mount St. Mary’s graduate.

French sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi created his first plans and model for the iconic Statue of Liberty in the New York studio of John LaFarge, a Mount St. Mary’s graduate from the Class of 1853.

LaFarge also introduced Bartholdi to Jeanne-Emilie Baheux de Puysieux, the woman who would model for the statue. Bartholdi and de Puysieux eventually married in LaFarge’s Rhode Island home.

Had this been LaFarge’s only contribution to the art world, he might have remained a footnote in history, but it is only a small piece of the art legacy he crafted for himself.

His interest in art began during his time at the Mount.

“In 1853, a student at Mount St. Mary’s College drew sketches of classmates … Wandering the Catoctin hillsides, he also sketched landscapes of Frederick County scenes. This youth, John LaFarge, found a love for art here in Frederick County and grew to become one of the greatest artistic minds of the 19th century in America,” according to the website for “The Dreaming,” a public art project in Frederick.

LaFarge was born in 1835 and began attending the Mount at age 15. Following his graduation, he became known as a painter, magazine and book illustrator, stained-glass window designer and writer. He was also a co-founder of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The museum’s website calls its founder, “A quintessential ‘Renaissance man’ of the American Renaissance, he responded to and encouraged the eclectic tastes and interests of his sophisticated patrons.”

Despite his impact on the world of art, LaFarge nearly became a lawyer. He even practiced law for a time after his graduation. “Though his interest in art was aroused during his college training at Mount St. Mary’s and Fordham University, he had only the study of law in view until he returned from his first visit to Paris, where he studied with [Thomas] Couture and enjoyed the most brilliant literary society of the day,” according to The Catholic Encyclopedia.

That changed when his father, Jean Frederic LaFarge, died in 1858 and John received a large inheritance. He was able to work at his art full-time.

LaFarge’s rise to fame began with a mural that transformed the interior of Boston’s Trinity Church in 1876.

He was also the first to experiment with opalescent glass and copper wire instead of lead lines to attach the pieces in stained glass work. LaFarge’s work was so unique, he held a patent for superimposing panes of glass. Louis Comfort Tiffany later commercially refined LaFarge’s techniques, which led to a lawsuit between the two men.

Besides being a founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, LaFarge also founded the Society of American Artists and the Society of American Mural Painters.

LaFarge also never forgot his alma mater, serving as the first vice president of the New York Alumni Association of Mount St. Mary’s College in 1905.

He died in 1910 and is buried in Rhode Island.

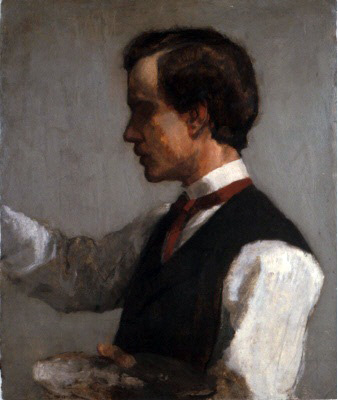

Portrait of William James

John La Farge

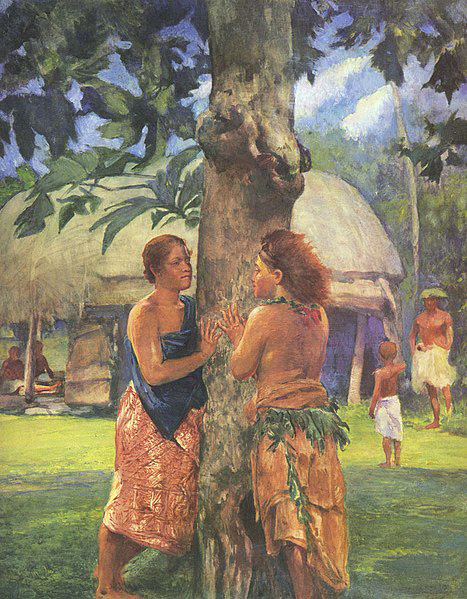

Portrait of Faase, the Taupo of the Fagaloa Bay.

You probably won’t recognize his name, but Thomas Meighan was once as big a movie star as Brad Pitt or Tom Cruise, and he was an alumnus of Mount St. Mary’s. He was one of the leading actors in the country in the 1920s, at one point earning $10,000 a week (about $125,000 in today’s dollars).

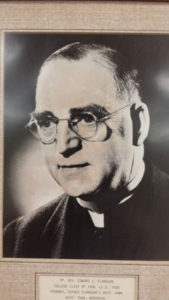

You probably won’t recognize his name, but Thomas Meighan was once as big a movie star as Brad Pitt or Tom Cruise, and he was an alumnus of Mount St. Mary’s. He was one of the leading actors in the country in the 1920s, at one point earning $10,000 a week (about $125,000 in today’s dollars). Father Edward Flanagan

Father Edward Flanagan Young Betty Jean Hixen was raised in a family of Polish and Irish descent, who were coal miners in Jordan, West Virginia. Just three miles away, her future husband, William (Bill) Meredith, lived with his family of Welsh and Irish ancestry. They were farmers. The two were destined to love, and met when she was a freshman and he was a senior, on the school bus ride to East Fairmont High School.

Young Betty Jean Hixen was raised in a family of Polish and Irish descent, who were coal miners in Jordan, West Virginia. Just three miles away, her future husband, William (Bill) Meredith, lived with his family of Welsh and Irish ancestry. They were farmers. The two were destined to love, and met when she was a freshman and he was a senior, on the school bus ride to East Fairmont High School. A Unique Life Experience

A Unique Life Experience

In preparation of the annual National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Service that is held in October in Emmitsburg, Maryland at the National Fire Academy, Emmitsburg’s fire personnel and volunteers fill multiple rolls year-round. For this year’s 33rd annual event held on the weekend of October 11 and 12, 2014, the folks at Vigilant Hose Company washed a huge U.S. flag then hung it to dry in the four-story stairwell at the station on West Main Street in Emmitsburg. Witnessing the flag, Wayne Powell, Executive Director of the National Fire Heritage Center (located within the Frederick County Fire and Rescue Museum on South Seton Avenue in Emmitsburg) said, “It was something to see.”

In preparation of the annual National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Service that is held in October in Emmitsburg, Maryland at the National Fire Academy, Emmitsburg’s fire personnel and volunteers fill multiple rolls year-round. For this year’s 33rd annual event held on the weekend of October 11 and 12, 2014, the folks at Vigilant Hose Company washed a huge U.S. flag then hung it to dry in the four-story stairwell at the station on West Main Street in Emmitsburg. Witnessing the flag, Wayne Powell, Executive Director of the National Fire Heritage Center (located within the Frederick County Fire and Rescue Museum on South Seton Avenue in Emmitsburg) said, “It was something to see.”