Dana French

45 Years in the Navy

by Richard D. L. Fulton

Note: Priscilla Rall contributed various materials for the purpose of writing this article.

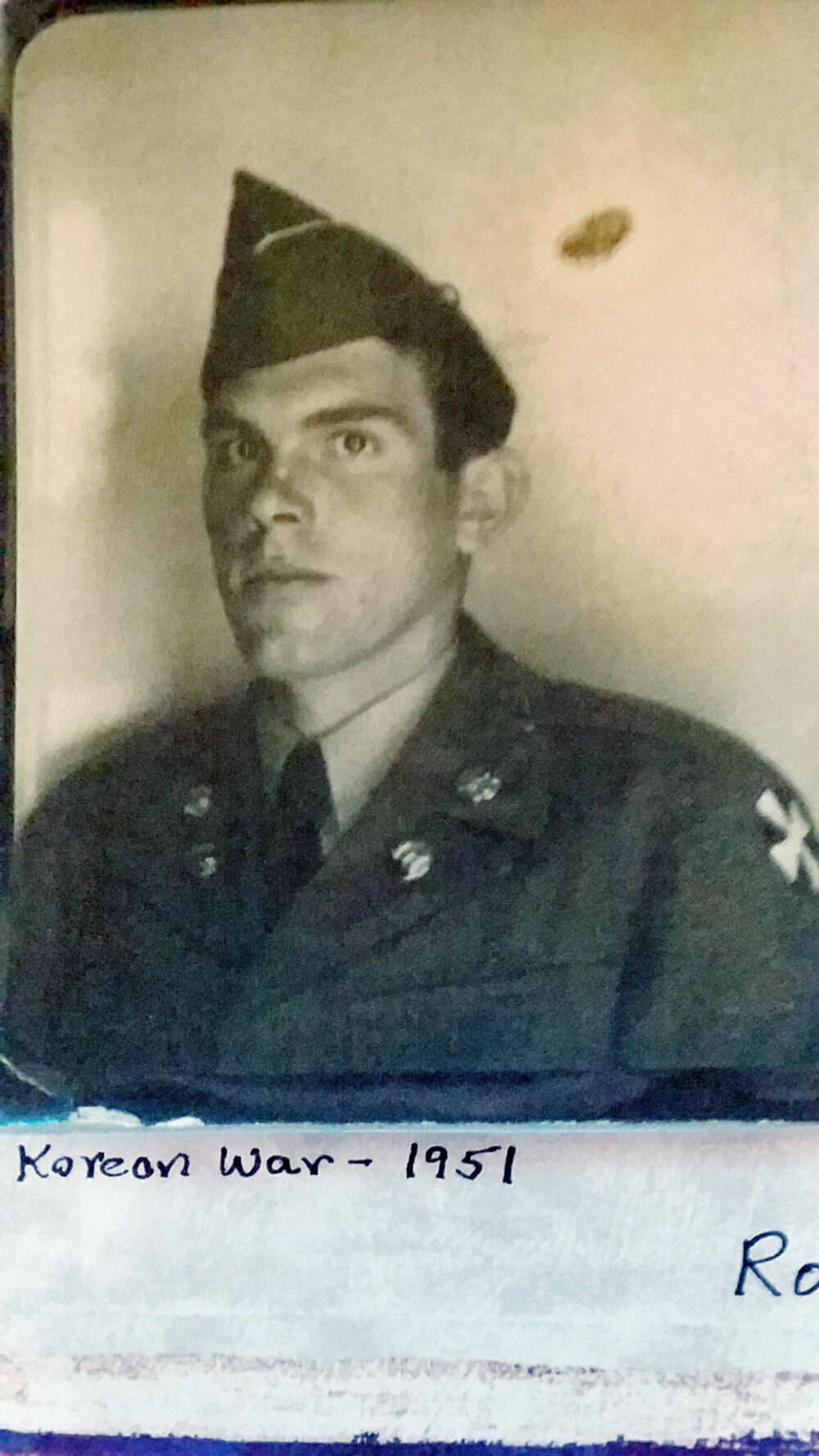

Dana French of Frederick County served aboard and/or commanded several Navy vessels over the course of the 45 years he served in the United States Navy, from 1955 through 1990.

Raised in Newburyport, Massachusetts, French decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and enlisted in the Navy at age 17. After French signed on with the Navy, he qualified to attend the Naval Academy Preparatory School (NAPS), in Bainbridge, Maryland.

French attended the academy as a sailor, and then graduated in 1961 as an ensign. He chose to pursue a career in the naval surface (non-submersible ship) service, as opposed to air or submarine services.

His first shipboard assignment came a month after he graduated, when he was assigned to the destroyer U.S.S. Coontz, which was then sent along with ships accompanying the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Ranger to the Middle East for two seven-month deployments. French served as the assistant 1st lieutenant in charge of the deck force, then became gunnery assistant at the end of the deployment.

French was then ordered as an executive officer in 1963 to report to the wooden minesweeper U.S.S. Whippoorwill during the Korean war. The minesweepers were wooden while metal alloys were employed wherever necessary—then to keep from triggering magnetic mines. The ships were responsible for cleaning mines from harbors for use by United States’ forces.

In the wake of the Tonkin Gulf incident (which technically triggered the Vietnam War), the minesweepers were sent on a “secret mission” to the Tonkin Gulf to screen a harbor for mines, rocks, and debris that would prevent the proposed port from being used.

In 1965 French was ordered to the U.S.S. Koka, an auxiliary ocean tug as Commander (the first such rank assigned to his academy class).

French said one of the more interesting incidents was when his ship was ordered to tow a “floating bomb” out to sea where it could be detonated to test how far around the world the detonation could be detected via deep sea sound channels. The “floating bomb” actually was a “Liberty” ship, made of concrete.

French was tasked with towing it, along with a second tug, to a desired location for detonation, which “seemed like a simple idea, except the weather turned bad. The weather really turned awful.” As the vessels approached to drop-point, the tow lines gave way, and the “floating bomb” was then loose. French was able to recapture the “Liberty” ship and begin towing it, but the scientists present decided to blow up the ship where they had it, rather than risk further issues trying to tow it to the original designated location.

During 1968, French was again heading back to Vietnam for seven months, this time in command of the guided missile destroyer U.S.S. Robison. He and the Robison became part of an operation deemed “Giant Slingshot,” a plan to ambush Vietcong attempting to cross two parallel rivers, using the cover of night, leading from Cambodia into Vietnam.

The Robison and other Navy ships under French’s command, joined by several riverine combat ships, were concealed during the day until nightfall, and then to rush the two river crossings and take out as many enemy combatants as they could, then fall back before Vietcong artillery could get a fix on their ships’ locations.

French was subsequently assigned as a weapons officer on the guided missile cruiser U.S.S Leahy in 1970, when the ship was sent off with its sister ship and an aircraft carrier to Gibraltar and then Jordan to counter a Russian move in that area, resulting in a stand-off and the retreat of the Russian ships.

After his services at sea, French had also subsequently developed a number of programs addressing officer leadership and enlisted men and organizational effectiveness. After his retirement from the services, he began a career as a self-employed organization development consultant and trainer, based in Frederick.

For additional information regarding Dana French, visit elementalimpactsolutions.com/dana-french-bio.