Rocky Ridge Woman Becomes POW

by James Rada, Jr.

Edna E. Miller of Rocky Ridge was a young, idealistic teacher in 1940. The graduate of Western Maryland College (McDaniel College) had taught at schools in Rocky Ridge and Thurmont, but her life changed when she joined the faculty of a school outside of Washington, D.C. and was sent to teach at the Brent School in Baguio in the Philippines. Charles Henry Brent founded the boarding school in 1909 for the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States.

The Japanese invaded the Philippines the day after they attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, and Edna’s family and friends lost contact with Edna. The Japanese, meanwhile, installed a Council of State to direct civil affairs in the Philippines. They abused the civilians, forcing many young women to act as “comfort women” for the Japanese soldiers.

Edna escaped this fate, but the Japanese imprisoned her. The Brent School closed during the war. It became a Japanese hospital and officers’ residential area. The Japanese Army sent the Brent School faculty and staff to a concentration camp called Camp Holmes in La Trinidad, according to the Brent International School website.

Back in the United States, “An attempt was made to learn of her whereabouts through the International Red Cross, but without success. She had been in the Philippines about three and a half years,” the Frederick Post reported in 1945.

Edna later told the press, “In all that time I received one 25-word message from my family and one package from the Red Cross.”

That 47-pound package came near Christmas 1943. “You should have seen the children scamper out on the green in broad daylight dressed in pajamas and shoes, the first they had had for many a long shoeless month. And Bagnio (sic) is not a place to be without warm clothing with its 200-inch rainfall and its coolness-70 degrees or less,” Edna said.

More importantly, the packages contained food and medicine that helped keep the prisoners alive in 1944, when their daily food allotment from the Japanese was 800 grams of moldy rice or corn.

“Conditions were so bad in camp with no medicine to stem the diarrhea, dysentery, anemia and malnutrition that even the doctors and nurses were sick. What those vitamins and sulfa drugs did for us, only the thousands of suffering internees could tell you,” Edna said.

The prisoners used the food and medicine they had received in their Red Cross packages sparingly since no one knew if they would receive another package.

Edna said the women shed tears over receiving bobby pins and powder, things they considered luxuries at the time. They were having to hammer out homemade pins from old iron on a forge or use bamboo pins.

Although the Millers hadn’t heard from their daughter in years, they prayed she was still alive.

The tide of the war began turning. American forces began retaking the Philippines in late 1944. Most of the Japanese in the Philippines surrendered on February 23, 1945. However, Gen. Douglas MacArthur continued routing the Japanese from other parts of the country until it was declared free of the Japanese on July 4, 1945.

In the meantime, the War Department announced on February 21, 1945, that Edna was one of the American prisoners freed as the American forces took Luzon. The Frederick Post encouraged friends and family to write to her, care of the Red Cross, but they cautioned people to mail more than one letter because getting mail to and from the islands still took weeks and could be unreliable.

“The night that we were liberated we had to leave our Bilibid prison to escape the fire surrounding it, and we were asked to leave all, save a handbag and we would come back for our other things,” Edna said.

It was during this time the Red Cross impressed Edna. The volunteers stepped in to help take care of the freed prisoners. They had even arranged for them to cable their families and let them know they were safe.

Edna was so impressed that she didn’t return immediately to the United States. She stayed to volunteer with the Red Cross and help others.

According to information the United States released years after the war, U.S. casualties in the Philippines were 10,380 dead and 36,550 wounded; Japanese dead were 255,795. Filipino deaths during the occupation was estimated to be 527,000 (27,000 military dead, 141,000 massacred, 22,500 forced labor deaths and 336,500 deaths due to war-related famine).

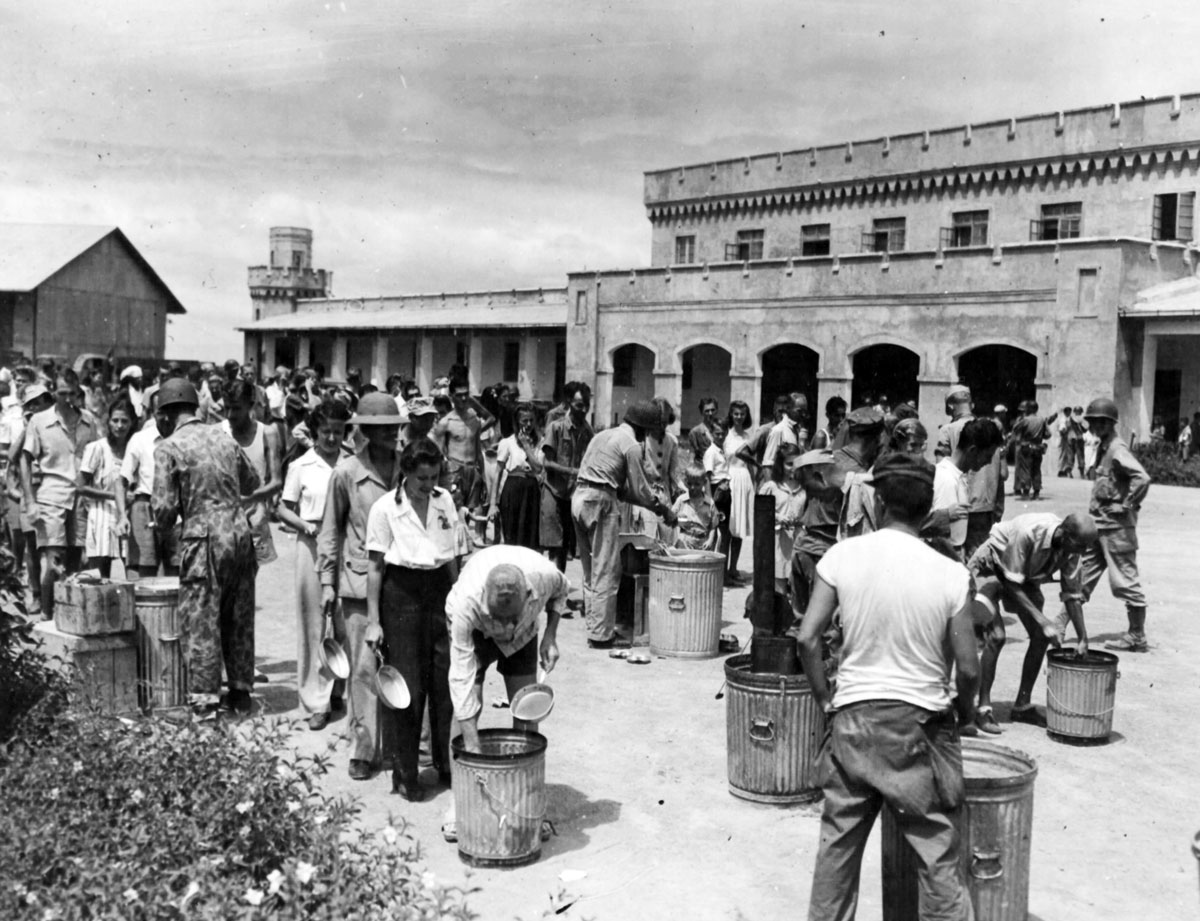

Prisoners liberated from a prison camp in Manila, Luzon, Philippine Islands, line up for their first square meal in over three years of Japanese imprisonment.

Courtesy Photos