How I Came to Know My Father ~ Part 3by Sally T. Grove

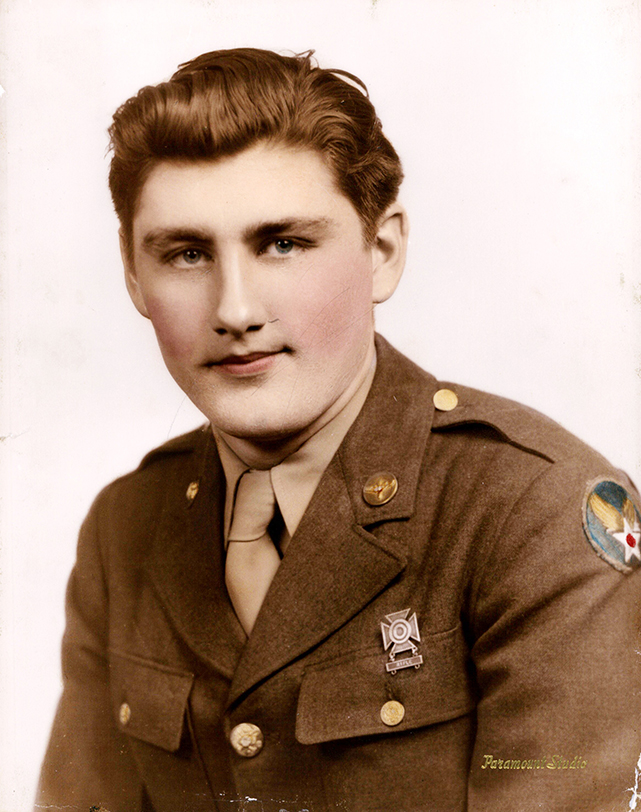

Courtesy Photo of Chester L. Grove, Jr. in Uniform

Courtesy Photo

I started to understand my father, Chester Grove when I was 20 years old in 1977. That’s when I found the journal he kept during World War II. I read about experiences he didn’t talk about… fighting in war. About the assault on the Rhine, he wrote:

Where I lay, there were two more of my buddies, so I crawled back along the wall trying to locate the rest but could not do so… The Jerries must have heard me for just then a pebble dropped from the wall about ten feet away… I realized that it might not be a stone after all. I hugged the ground as tightly as I could, pushing my body against it. I also, in that split second, turned my face against the wall. Then it happened, a blinding flash and a deafening noise. I could neither see nor hear. Dirt flew all over me.

A grenade had taken my father’s sight and his hearing. A dark veil hanging over his bright blue eyes. How it must have magnified his fear!

I felt my face for I was sure it must be bleeding, but then my sight returned and gradually my hearing, although my ears kept ringing… I looked at my buddy in front of me and his head was smeared with blood as well as his foot and legs. I shook him thinking he was dead but he moved, then another grenade not quite as close hit the ground. A blinding flash and blast followed, however it did not touch us.

Concern for others, even in the face of adversity does not surprise me. Although my family didn’t have much growing up, we never did without, thanks to my father. Dad had just three suits: one for winter, one for summer, and one to wear when the in-season suit was getting cleaned. His children, on the other hand, went shopping each September for new school clothes, and each spring, we shined in our new Easter outfits.

I knew then that they would keep grenading us till we were dead or came out. I never prayed so hard and so desperately in my life, I know that I could never be an atheist, ever, and that anyone no matter what his feeling, put in the same situation would ever deny God.

Dad never talked about religion, he lived his belief. Mom was the one who took us to church on Sundays. Dad came for Baptisms, First Communions, and Confirmations, but Sunday mornings were always Dad’s time at home, while we went to mass with Mom. I have never known a more-loving man than my father, so I am not surprised that he professes his belief in God, still he never talked to us about his faith.

In those few minutes, which seemed a year, I saw visions of my favorite fishing places and hunting territory… saw them clearly as if I were there. I pictured mom, dad, and all the family, as well as all my friends who I was sure I would never see again.

My dad’s sister, Aunt Kitty, told me that Dad was always her best friend. They were closest in age of all their siblings and played together as children. They fished in Carroll Creek and rode their bikes through the streets of Frederick. I once read a letter that Dad wrote to his father; he signed his letter, “Love, Your Fishing Buddy, Tommy.”

Again a grenade dropped within 20 feet and I pressed into the earth… a voice spoke in broken English “Hello boys, come out, ve know you are there.”… I scarcely breathed for each breath sounded like a bellows, at least in my ears… I was soaked to the skin in blood and water and was shaking like a leaf in the wind. I thought of my first-aid kit with its sulfa drug to keep my wound from infection, yet I dared not move for every move brought a grenade.

The waiting must have been torture. Dad knew that the Germans were close, and they had his life in their hands.

Night started to fade… empty boats floated by… then we heard footsteps on the beach… the Jerries were afraid to come down in the darkness for fear of ambush. They had waited until they had light enough to see and then investigated. We were prisoners.

Dad’s fear must have been great when he heard footsteps approaching. The soldier became a prisoner.

At least the constant fear of uncertainty and falling grenades was now over. We had lain under the wall from 12 p.m. till daylight… four and a half hours of terrible uncertainty, awaiting death or capture or possibly help.

Dad relinquished one state of uncertainty for another. Perhaps being a prisoner of war was better than lying in wait for an unknown fate.

We were searched and stripped of all equipment but our clothes, even our first-aid pouches were taken, as well as our cigarettes, water, rations, and anything the Jerries decided they wanted. I refused to give up my pay book and finally they agreed to let me have it… I then tried to get the other fellow’s books back but they would not allow this.

Why was his pay book so important? What did it mean to a soldier?

Certainly a soldier got paid whether they presented a pay book or not.

Thankfully, by the time I knew my dad, he had given up cigarettes for a pipe. I know that pipes are bad for you, but to this day, pipe smoke makes me think of my father.

We had four guards for the eight of us and we were forced to carry a fifty pound box with us. We climbed up a steep, rocky ridge just before the sun peeped over the horizon. The going was rough…those hills were hundreds of feet high and very steep. Our (the U.S.) artillery had begun firing again and we were in constant danger from our own shells…We were really scared and I never thought we would make it through there alive.

I had seldom seen my father show raw emotion, except, that is, when Dad made a decision to reverse a doctor’s recommendation for our family. I was 10 when my brother Craig was born. We didn’t know it for several years, but Craig’s brain had been damaged during the birth process—Craig was developmentally disabled.

The doctors told my parents that Craig and our family would fare best if Craig moved into a group home.

Unfamiliar with the plight ahead, my parents placed Craig in Kemp Horn Home.

Our family was not allowed to see Craig for a month. When we finally visited, it was raining. “Song Sung Blue” played on the radio. My family’s hearts mirrored the rain as we visited with Craig. My father decided that doctors do not know best, and Craig came home with us that very day. My family never looked back.