Stories of What It’s Like Returning Home After 25 Years

by dave ammenheuser

Sitting on top of Haleakala in Maui in late October, it was the perfect place to reflect on the craziness of the past year and what lies ahead in the future.

As I’ve chronicled here throughout the past year, I quit my life-long sports journalism career last October, sold my Nashville house, and moved back East to take care of my parents’ estate. My father died in September 2020; my mother passed in December. The tragedy trifecta began when my father-in-law died in July 2020.

After spending a year clearing my father-in-law’s Delaware home and my parents’ Creagerstown home, then selling both houses, it was time for a much-needed vacation to finally let the absorbed emotions of the past year release. It was finally time to shed a tear or two.

My wife and I planned the trip to Hawaii for several years. It was our gift to each other for our 25th wedding anniversary. And, geesh, did we need it.

Unwinding in Hawaii, the one common theme that constantly came to my mind was family. Simply put—as I’ve stressed to my own two children over the past two-plus decades—nothing is more important.

Growing up in Thurmont, my childhood was not perfect. But, as I aged and lived in eight different states, becoming friends with thousands, I’ve realized that nobody’s family is perfect. All families come with their own quirks, many of which remain private and out of the public eye.

I have also become keenly aware of the need for planning for the future. Prior to leaving for Hawaii, my wife and I spent many hours preparing important legal documents: our will and trust, health directives, and power of attorneys. It’s something we always talked about doing but never got around to completing, until last month.

Thankfully, my father-in-law and my parents had their wishes written down in a legal format. That’s the good part.

The bad part is that we rarely talked about them until they became terminally ill.

Over the past year, I’ve reunited with many of my childhood and high school friends. If there’s one bit of advice that I can give each of them (or anybody reading this column), it’s this: If your parents are still living, spend some quality time and sit down with them and talk about their future. It’s important to know what they want their care to look like as they age. You can’t fulfill those wishes if you don’t know what those wishes are.

My mother died of breast cancer that spread to other parts of her body. My father died of congestive heart failure. My father-in-law died from metastasized melanoma cancer that spread to his brain.

My father died instantly; my mother and father-in-law slowly declined over a period of months.

All had completed health directives. My parents (albeit surprisingly) did theirs a few years ago. My father-in-law needed a lot of prodding from my wife and her brothers before he completed his shortly after his terminal diagnosis.

The entire past year would have been more difficult and painful if any of them had not completed the simple form.

Death isn’t a fun subject for any aging person with a challenging diagnosis. Heck, death is the last thing that they want to think about. However, the document is important if your loved one, due to declining health or a medical accident, is unable to cognitively make decisions for his/her own care. It’s a roadmap and guide with legally binding instructions for healthcare providers. You can search online for free fill-in-the-blank forms.

After the healthcare directive is completed, it’s important that you discuss the document’s contents and its location with other loved ones, especially siblings. This is important because some of the information may surprise you (for example, I had always thought my mother wished to be buried, but she relayed to me later and included in her health directive that she wished to be cremated).

A Last Will and Testament is equally important. Your parents don’t need to share the contents of the will with you (my parents’ will certainly had a few surprises), but it’s important to know where important estate documents are kept, so you can access them when the time comes.

After being away from Thurmont for 25 years, I’ve spent the past year writing funny and heartful anecdotes about my return home. But none of those words are as important as the 700 on this page.

David and Maura Ammenheuser and their parents on their wedding day in 1996. It’s the only photo of all six of them together. All four parents are now deceased.

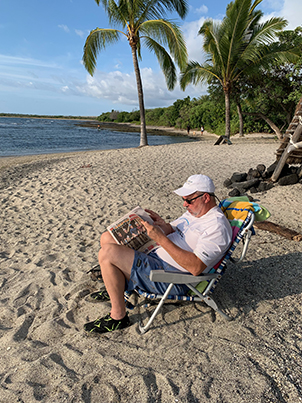

Dave Ammenheuser reads The Catoctin Banner’s October issue while relaxing on the beach at Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park in North Kona, Hawaii.

Born on April 5, 1921, just north of Thurmont at Franklinville, to Roy and Blanche Baker, was a boy they named George. George had three brothers and two sisters: Raymond, Donald, and Leroy, and Ruth and Helen (nicknamed Tootie). In 1940, at the age of nineteen, George decided he wanted to join the military. His brother, Raymond (nicknamed Hun), had already been in the military several months, and was somewhere around Washington, D.C.

Born on April 5, 1921, just north of Thurmont at Franklinville, to Roy and Blanche Baker, was a boy they named George. George had three brothers and two sisters: Raymond, Donald, and Leroy, and Ruth and Helen (nicknamed Tootie). In 1940, at the age of nineteen, George decided he wanted to join the military. His brother, Raymond (nicknamed Hun), had already been in the military several months, and was somewhere around Washington, D.C.