The Blizzard of 1932

Richard D. L. Fulton

On March 7, 1932, Frederick County residents awakened to assess the damage inflicted upon their respective communities by a severe overnight blizzard that had beset the region.

Instead of continuing to seek encouragement from the newspapers as to any signs of relief from the economic oppression of the Great Depression, readers instead learned of the damage that nature had inflicted. Stories of all the damages and deaths associated with the storm competed with headlines of the latest news regarding the kidnapping of the son of Charles and Anne Lindbergh, which had taken place less than a week earlier.

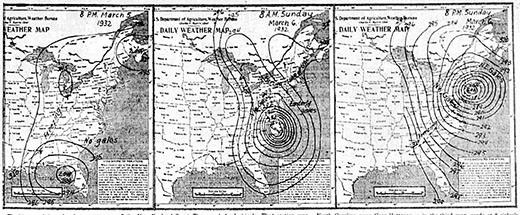

The “nor’easter” that moved into Frederick County during the evening of March 6, and raged on into the early morning hours of March 7, had originated in the Gulf of Mexico on March 5, moving rapidly northeastwardly along a track paralleling the eastern flank of the Appalachian Mountains until it made its way offshore in New England, thus, impacting the entire middle Eastern Seaboard of the nation.

The storm generated sustained winds of up to 60 miles per hour, while temperatures plummeted down from 45 to 20 degrees (apparently not accounting for wind-chill effects), according to The (Baltimore) Evening Sun.

Snowdrifts in the wake of the storm in Frederick County exceeded five to nine feet in depth.

“And then came the dawn,” The (Frederick) News wrote in its March 7 paper, further stating, “With it, Frederick found: paralyzed electric service, crippled telephone and motor communications, hundreds of stranded motorists… the most tangled snarl in a decade, and a temperature of 15 degrees…”

Frederick County sustained widespread damage. Hundreds of power and telephone lines were downed in the county, The News reporting that “crews would actually be busy for months before the final damage (to the power and telephone infrastructure) was repaired. (More than 1,000 poles were reported down in the Middletown area alone.)”

Not only were roads clogged with stranded vehicles (over 100 of which were towed to Frederick alone, in the wake of the storm), but streetcars (also known as trolleys) were stranded wherever they were running at the time the power went out, including the Thurmont Trolley.

Few deaths associated with the storm were reported in the county. Two were reported as having frozen to death during the storm, and a third (identified only as a man named Pickett of Lisbon) had sustained a heart attack while shoveling snow.

On March 7, The Sun identified the two individuals who had frozen to death as having been Catherine B. Overs, 30, of Lime Kiln, and Thomas D. Tyler, 25, of Buckeystown. According to The News, Tyler’s body had been spotted by a passing train crew. Overs’ body was also located by the train crew less than 500 yards from that of Tyler’s.

The newspaper reported that Overs and Tyler had abandoned a stalled car that had originally contained six individuals altogether, and they had struck out on foot to seek help. The Sun further reported that Overs and Tyler “left the car and tried to make their way over the tracks of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to a farmhouse, but were apparently blinded by the storm and became lost.”

The four individuals who had remained in the stranded car were subsequently rescued.

Maryland suffered only one additional death, but more than 40 individuals lost their lives in the balance of the storm’s path (including five individuals who drowned when a Coast Guard surf boat capsized).

The News reported on March 8 that Frederick County was essentially isolated from the rest of Maryland for nearly 24 hours, but that the isolation effect had begun diminishing into Tuesday as roads were reopened (the roads from Frederick to Thurmont and Emmitsburg were yet to be cleared). Railroads had been sufficiently cleared to then permit the trains to run, while work continued in restoring the power and telephone infrastructure.

Structural damage was surprisingly limited, with losses primarily involving the loss of shingles and chimneys, along with blown-out windows and damage to doors.