T h e Y e a r i s…1 9 2 8

by James Rada, Jr.

She Wa s the F i r s t L ine in Fire Defense

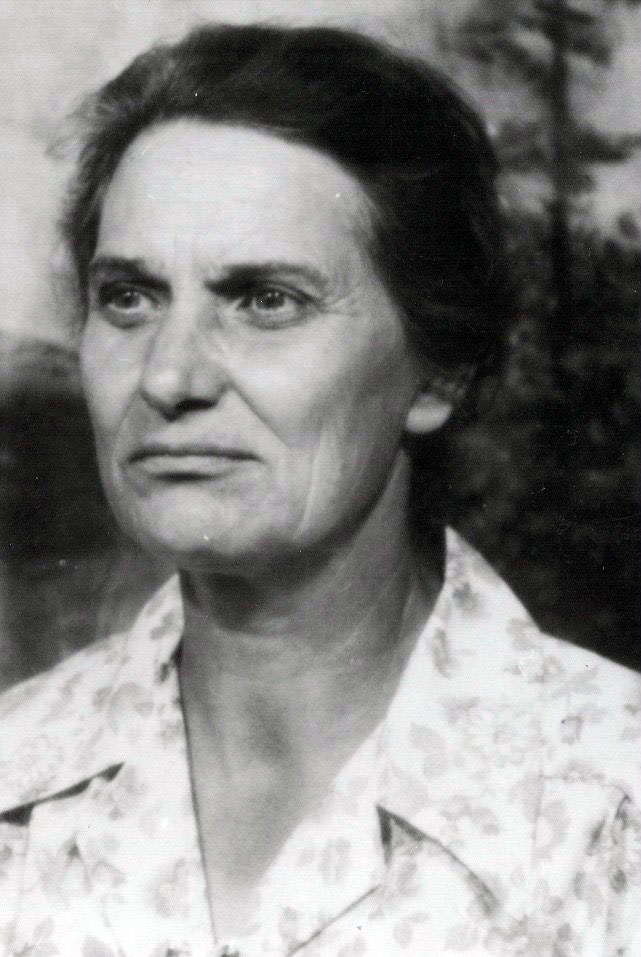

Photo Courtesy of findagrave.com.

Alice Willard knew all about struggling to get by. The Foxville resident was a 30-year-old single mother of an 11-year-old son, living in a rural area. Even though she had family who could help watch her son, Atley, Alice still needed to earn a living to support the both of them.

In April 1928, she became the only female “lookout” in Maryland. C. Cyril Klein, the district forester for Western Maryland, appointed her the lookout for the Foxville fire tower. A lifelong resident of Foxville who lived in a house her father built the year she was born, Alice knew the area she was to watch over.

“She went on duty Wednesday [April 4] and for the next eight weeks, until about June 1, she will occupy a small room at the top of a 60-foot steel tower in the heart of the Catoctin mountains, about 12 hours a day, on the lookout for mountain fires,” the Frederick Post reported.

Her pay for this job was $60 a month (about $925 in today’s dollars). It was a low-paying job, even among common laborers at the time, but it helped pay her bills.

From the fire tower, Alice had a 12-mile view in every direction.

“At the first indication of fire or smoke, she will telephone to the nearest warden, who in turn will investigate the fire. If it is of a threatening nature, a force sufficient to combat the flames will be summoned and efforts will not be relaxed until the blaze is extinguished,” the Frederick Post reported.

She had experience with the job. She had substituted when her brother needed time off from the job years earlier.

“While she will be some distance from the nearest house, Mr. Klein said she is courageous and he added that she knows how to shoot,” the newspaper reported.

Not only was Alice the only female lookout in Maryland at the time, she was the first woman put in charge of a fire tower in the state. Women had done the work before, but only as a substitute or an assistant.

She said of her experience years later in a Frederick News Post article, “Indeed there were lots of fires! And no lightning ever set those fires. Men set fires! Tossing a cigarette or some other fool thing, that’s what done it. Many’s the fire that was set on purpose, too. Did you know that? I’ll tell you just why! They’d set fires to burn off a clearing in the woods. Then the huckleberries would grow up thick in the burned out places. Huckleberries were a big cash crop here in those days. Many a berry’s been picked and sold for three cents a quart. Every child on the mountain’s picked huckleberries at one time or other.”

In 1930, she was mentioned in an article talking about a rash of fires on Catoctin and South mountains. She had been the first lookout to identify some of them.

She was named an assistant fire warden in 1931.

In 1933, she had a near-fatal encounter with a copperhead that the Hagerstown Morning Herald said she handled with “remarkable coolness and bravery.” She was burning brush while on the job when the snake bit her above the ankle. “She cut open the wound and applied a tourniquet to stop the circulation of blood, then walked to a neighbor’s house, where she secured medical attention.”

She left her job with the State of Maryland in 1934.

The Frederick News noted in 1971 that Alice was still driving a tractor, chopping wood, farming, feeding livestock, keeping house, quilting, sewing clothes, baking, and canning at age 76.

She was also living alone. She had never married, and her son had died from cancer in 1962 at 45 years of age.

“She values her privacy, resents any encroachment upon her land or her rights, and is the personification of the attitudes and traditions of the mountain folk for over two centuries,” Ann Burnside Love wrote for the Frederick News.

Alice died in 1993, a week before her 98th birthday. She is buried in the Mt. Moriah Lutheran Church cemetery.

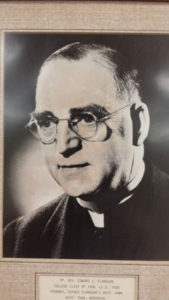

Father Edward Flanagan

Father Edward Flanagan