PFC John Little, Emmitsburg

KIA in the Liberation of Bizory

by Richard D. L. Fulton

John William Little was born on December 19, 1910, to parents John William and Minie Little, and resided on Frederick Street, Emmitsburg, Maryland, and had two sisters, Valerie and Anna, and three brothers, Robert, Roy, and James.

James was included as one of the brothers by a write-up that appeared in The (Frederick) News on March 12, 1945. However, James is not mentioned in the 1930 census. The census lists the Little’s three brothers as Robert, Roy, and Charles.

According to his draft card and enlistment records that Little had filled out when he was 90, he indicated that he was employed at St. Joseph’s College as a fireman before entering service, and that, regarding his education, he had attended “grammar school.”

Little was enlisted at Fort George G. Meade on April 3, 1942, and given the rank of private. He was subsequently stationed at Camp Cook, California, and Camp Chaffee, Oklahoma, before going overseas (at age 34) and was a member of a tank crew in the 68th Tank Battalion, 6th Armor Division, in General George S. Patton, Jr.’s Third Army.

Little was given leave in December 1943, to return home, following the death of his father, to attend the funeral.

The 6th Armor Division entered the war via Utah Beach, Normandy, July 19, 1944, ultimately fighting its way through Northern France, Central Europe, and finally, the Ardennes.

He was injured in November 1944, when the tank in which he was traveling was knocked out by enemy fire, resulting in his being wounded in the face and left leg. The Gettysburg Times Reported on January 30, 1945, that “He was able to able to return to action shortly thereafter… after the medic treated him.”

Little wrote his last letter home on December 27, 1944, stating that “he was well, and expecting to be to be sent to some other country, which he could not identify, within a short time,” according to The Gettysburg Times.

That “some other country” would be Belgium, and Little would soon find himself and 6th Armor Division the rolling towards Bastogne, a Belgian city that the German troops were in the process of laying siege to, as part of an over effort ordered by Adolf Hitler to attack allied forces that were slowly griding their way towards Germany – an overall engagement that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

The Battle of the Bugle would become Hitler’s last stand before his 12-year-long “1,000 Year Reich” began to implode from the allies tearing into it from all directions.

The German siege of Bastogne was ultimately broken by the U.S. forces, including the 6th Armor Division, during seven days of battle, from December 20 to December 27, 1944. In January, 1945, the U.S. forces were ordered to begin driving off the German troops that remained in the area.

As a part of that effort, the 6th Armor Division was ordered forward to take the village of Bizory (sometime misspelled as Bixory on some web sites) away from its German occupiers. Bizory lies about 2.6 miles northeast of Bastogne.

The village was soon liberated, and the 6th Armor Division was solely credited with accomplishing the objective. Unfortunately, Little, who would make his final stand in the fight to liberate Bizory, was initially declared missing in action on January 8, 1945. He was 34 at that time. Little was shortly thereafter reclassified as killed in action. But it would appear that Little’s body was never recovered. His name is listed on the “Tablets of the Missing” in the Ardennes American Military Cemetery, Neuville-en-Condroz, Arrondissement de Liège, Liège, Belgium.

Little was awarded the Purple Heart W/Cluster and was also posthumously promoted to private first class.

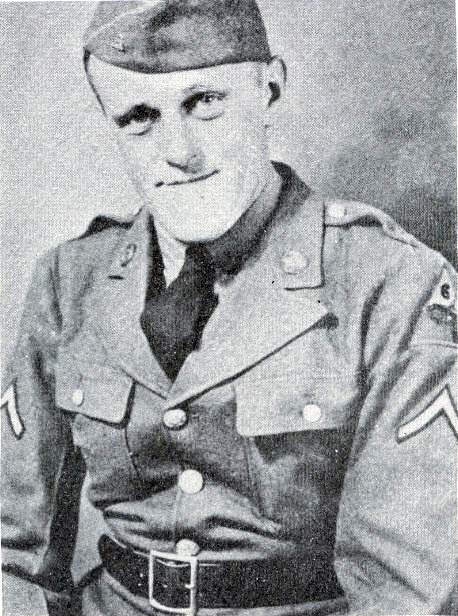

Photo Courtesy of U.S. Army public domain

PFC John William Little, Photo Courtesy of findagrave.com

“Some days I wonder if it’s a blessing or a curse to live to be as old as I am,” said

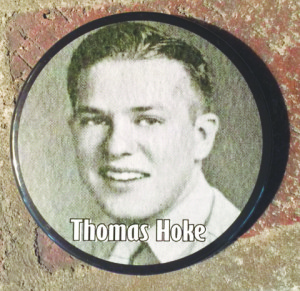

“Some days I wonder if it’s a blessing or a curse to live to be as old as I am,” said Emmitsburg native and ninety-two-year-old World War II Veteran, Tom Hoke. “I’ve lived plenty of good times and plenty of bad times. I hope, when it’s my time to go, that I go without being a burden on anyone.”

Emmitsburg native and ninety-two-year-old World War II Veteran, Tom Hoke. “I’ve lived plenty of good times and plenty of bad times. I hope, when it’s my time to go, that I go without being a burden on anyone.”