Note: This is the third of three articles about the wreck of the Blue Mountain Express between Thurmont and Sabillasville in 1915.

by James Rada, Jr.

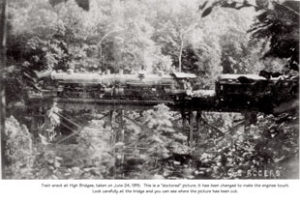

On June 25, 1915, the Blue Mountain Express bound for Hagerstown crashed head-on with a mail train coming east from Hagerstown, crumpling the two engines and sending a baggage car off the bridge where the wreck occurred and into the ravine below. Coleman Cook, engineer; Luther Hull, fireman; J. R. Hayes, fireman; Mrs. W. C. Chipchase, Baltimore; and Walter Chipchase, Baltimore, all died in the crash. Twelve others suffered serious injuries.

Edgar Bloom, a dispatcher for the Western Maryland Railroad, took responsibility for mixing up the right-of-way orders issued from Hagerstown that had caused the crash.

What if there was another contributing factor in the accident that no one realized because it had happened months earlier?

William H. Webb was a sixty-five-year-old watchman on the bridges west of Thurmont. Each day, he would walk to his shanty next to the bridges from his home on Kelbaugh Road. Every day, his wife, Sarah, would have one of their children or grandchildren take William his lunch.

“As watchman of those bridges, Mr. Webb’s position was an important one. The safety of many passengers and trains depended upon his watchfulness during the hours of the night. He walked those bridges at regular intervals during all hours of the night,” the Frederick Post reported.

By 1915, he’d been an employee of the Western Maryland Railroad for thirty-five years. His job was isolated, but he enjoyed it.

Webb was Roger Troxell’s great-grandfather. According to stories that his mother told him, “One of the children or grandchildren took him his lunch one day. It was pouring down rain and he found him (Webb) sitting on the railing holding his umbrella, and he was dead.”

This differs from the accounts in the Frederick Post and Catoctin Clarion. They reported that the day watchman had found William lying beside the cross-tie block on February 24, 1915.

“When found his overcoat was drawn up over his shoulders, and a raised umbrella lay beside him,” the Frederick Post reported.

The Catoctin Clarion explained that it appeared as if Webb had come east from his shack, across the iron bridge to “signal” the Fast Mail train going west soon after 6 o’clock, and while walking to his post east of the bridge was stricken with heart trouble and died.

The day watchman telephoned to Thurmont and Dr. Morris Birely, and Magistrate E. E. Black came out to the bridges to examine the body. No marks were found on it, and Birely said that heart failure was the cause of death.

Although this was months before the summer wreck, there’s no indication that another watchman was hired to replace Webb. Also, one of the trains that wrecked was the fast mail train that Webb usually signaled.

Had Webb still been alive and on the job, he may have been able to signal the trains to stop before they wrecked on the bridges. Bloom may also have been able to call the shanty directly about the mix-up, rather than telegraphing a message to the Western Maryland Railroad Station in Thurmont in the hopes to stop the train before it left the station.

William H. Webb

On June 25, 1915, the Blue Mountain Express, bound for Hagerstown, crashed head-on with a mail train traveling east from Hagerstown, crumpling the two engines and sending a baggage car off the bridge, where the crash occurred, and into the ravine below.

On June 25, 1915, the Blue Mountain Express, bound for Hagerstown, crashed head-on with a mail train traveling east from Hagerstown, crumpling the two engines and sending a baggage car off the bridge, where the crash occurred, and into the ravine below.