New Find Enhances Record

Richard D L. Fulton

There was a time when Frederick and Adams counties looked more like an alien world than that which exists today.

A primordial lake (dubbed Lake Lockatong) existed from Rocky Ridge, growing in size towards the northeast, as it sprawled through Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and into New York State. Some believe that this great lake covered an area equivalent to the presently existing Lake Tanganyika in Africa, at some 20,000 total miles in size. Often, vast mud flats bordered the huge freshwater lake, giving way to conifer forests (based on fossil evidence gathered outside of Rocky Ridge).

This was during a period of time classified as the Late Triassic, some 220 million years ago.

Based on fossil excavations in Rocky Ridge and another nearby site, fossils recovered indicate that the lake teemed with fish, mostly those related to the present-day gars, sharing the water with five-to-six-foot coelacanths (whose ancestors gave rise to land vertebrates), and an ancient aquatic gator-like (but unrelated) reptile called Apatopus.

It should be noted that the reptiles and dinosaurs discussed are known only from their tracks, with the exception being Rynchiosauroides (noted below) whose body impressions have also been recovered at Rocky Ridge.

Hundreds of two-to-three-foot-long lizards (called Rynchiosauroides) patrolled the shorelines, diving into and paddling their way within the shallows in search of snails, clams, and freshwater shrimp, while prehistoric crickets, beetles, and millipedes scurried about the mudflats.

The lizards were occasionally joined by at least one species of dicynodont reptiles in their quest for more food. The dicynodonts, though reptiles, were also ancestral to the first mammals, and those of Rocky Ridge apparently established that these unique animals survived longer than previously assumed before, themselves, becoming extinct.

But the local evidence of the beginning of the rise of another group of animals in the Late Triassic —the dinosaurs—can be found a little further north in Adams County. Most of the dinosaurs during this period of time in the Mason-Dixon area ranged from a few feet in height or length to 12 feet.

The latest evidence of the local presence of dinosaurs occurred on June 9, 2012, when a remarkable bed of dozens of dinosaur tracks was found at an undisclosed, secured site located on private property, southwest of Gettysburg (for security purposes, The Catoctin Banner agreed not to reveal the exact location of the ongoing excavation, although the reporter was permitted to visit the site).

The discovery was initially made by Brian Cole, a member of the Franklin County Rock and Mineral Club, while hunting for crystals in the limestone deposits. Cole stated that the collectors he was with started finding fossil mud cracks and gathered up several specimens to take home. He later discovered one of the slabs had a clearly defined dinosaur track on it.

The find resulted in return trips to the site, which ultimately resulted in the discovery of dozens of dinosaur tracks, along with non-dinosaurian reptile tracks. To date, more than 40 tracks have either been removed from the site or still remain on-site. How many remain to be found? Only time and further exploration will reveal.

The site in question consists of limey layers of rock which likely represents the shoreline of Lake Lockatong. Aside from the reptiles Rynchiosauroides and Apatopus, the new site added the tracks of two more (non-dinosaur) reptiles to the list, Desmatosuchus (which bore some resemblance to a crocodile with prominent spikes on its back and heavy back armor) and two different species of Brachychirotherium.

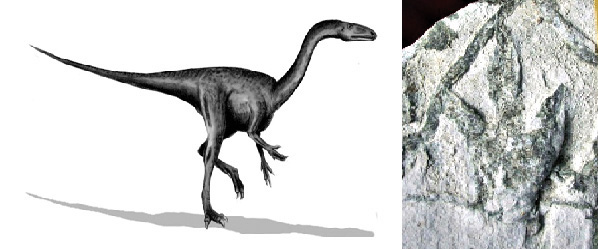

The primary dinosaur present at the site has been identified as Grallator, also known only from its tracks, but it is believed to be related to better-known Coelophysis, whose skeletal remains have been found in New Mexico. There may be what turns out to be species of Grallator at the site, one larger than the other. The much more plentiful smaller tracks may represent a different species of Grallator than the scarcer larger version.

The Grallator were bipedal carnivores, potentially ranging up to more than nine feet in height, and apparently hunted in packs. Over two dozen tracks were found on one layer at the site, all heading in the same direction. If Grallator was as Eastern Coelophysis, it could have had “feet (with) three main claws and a fourth, smaller claw positioned further up the foot,” and “The arms (that) were adapted for grasping and holding prey but are not thought to have been particularly powerful, a long and thin head, with jaws containing “around 50 small, sharp teeth,” according to Activewild.com.

Grallator and Coelophysis are among the oldest known dinosaurs, and it is generally held that they primarily ate insects and other small animals. As has been demonstrated by finds made at the Rocky Ridge site, there was no shortage of insects and small reptiles living in the area during the Late Triassic Period.

In 1895, James A. Mitchell, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, found nearly two dozen, 220-million-year-old dinosaur footprints on two flagstone (shale) slabs found in the pathways leading up to Saint Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church in Emmitsburg, thus making them reportedly the only dinosaur tracks that had been found in Maryland from this period of time (the Triassic Period).

The tracks appeared to have been those of Grallator. One of the two slabs that were found by Mitchell is presently on display at the Maryland Science Center.

But the first “mother lode” of dinosaur tracks, which also included non-dinosaurian reptile tracks, including dicynodont, occurred in Adams County in Trostle’s Quarry near York Springs when the tracks were discovered by Elmer R. Haile. Haile made his discovery in the summer of 1937 when he and some associates were gathering stone for the Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in a bridge; they were building the bridge on South Confederate Avenue over Plum Run.

The Gettysburg Times reported on August 3, 1937, that three dinosaurs who left their tracks in the quarry were identified by Arthur B. Cleaves, state junior geologist and paleontologist, as Anchisauripus exsertus, Anomoepus scambus, and Grallator tennis, all three being bipedal (standing upright on two legs). The newspaper also reported in December 1937 that approximately 150 tracks were recovered.

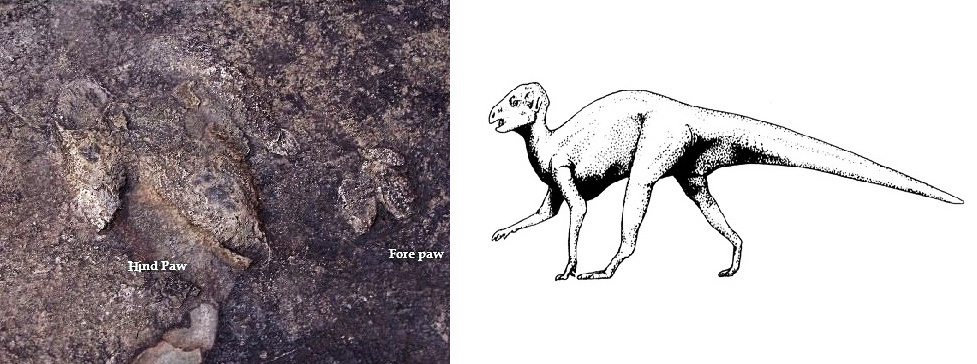

The two blocks containing the dinosaur tracks that made it into the top layer of stones on the Plum Run Bridge have been identified as Atreipus milfordensis, a plant-eating dinosaur that walked on all four legs, and Anchisauripus sillimani, another bipedal meat-eater. The Trostle’s Quarry tracks have been dispersed over time to such places as the Smithsonian Institute, the William Penn Museum, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburg, the Adams County Historical Society, and the bridge on the Gettysburg Battlefield (where they remain exposed and unprotected).

As an aside, the species names of the dinosaurs (and reptiles) noted in the article can, and may have, changed over time. Paleontology, or the study of prehistoric life, is a constantly evolving science, in and of itself, and as more is learned about a given prehistoric species, sometimes new findings can result in name changes.

Grallator

Adams County Grallator tracks (new site).

Photo Courtesy of Robert Weams (USGS retired).

Illustration Courtesy of National Park Service.

The Grallator were bipedal carnivores, potentially ranging up to more than nine feet in height, and apparently hunted in packs.

atreipus

Atreipus tracks (Plum Run Ridge).

Photo by Rick Fulton.

Illustration Courtesy of Columbia University.

Atreipus, a plant-eating dinosaur that walked on all four legs.