Like Father, Like Son

by Priscilla Rall

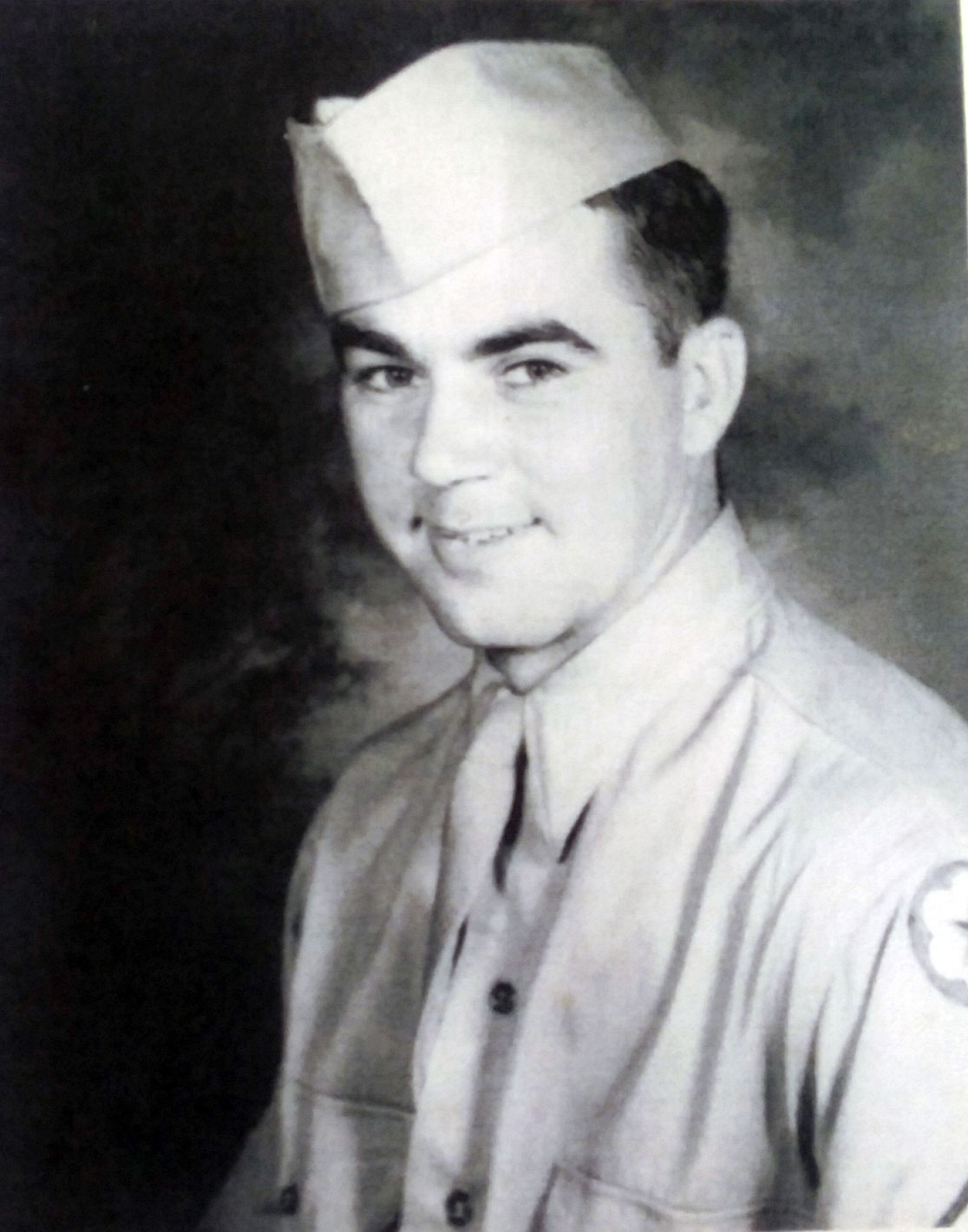

The first Baker, Henry, came to Maryland in 1742. He settled on a farm near Unionville, where his descendant, Wilbur Baker, farmed in the early 1900s. Wilbur only left the farm to serve in WWI in a supply company, driving a truck carrying supplies and sometimes the wounded in France. When he returned to the United States, he married Emma Glisan. They had two children: William Glisan Baker (born in 1923) and Betty Baker Englar. Betty’s husband, Donald, was a coxswain in a Higgins boat on D-Day in Normandy. William, or Bill, took a different route.

Bill grew up working on the home farm, milking cows by hand, making hay, and husking corn. He remembered the fun young people had at husking parties held at night under the full moon. Then they gathered ears of corn in baskets and threw them onto wagons to take to the corn crib by the barn. His mother was an excellent cook. Bill’s favorite meal was having breakfast after milking. It consisted of pudding and hominy, not the choice of many today. Emma really had her hands full at threshing time when she would have to feed about 18 thresher men.

Bill attended a one-room school, which eventually became the Linganore Grange Hall, and then to Linganore High School. In the fall of 1940, he began college at the University of Maryland, majoring in agricultural education.

Also, Bill’s uncle, Monroe Stambaugh, his cousin, Nevin Baker, and good friend, Warren Smith, served in the war. Warren was captured in the Battle of the Bulge and was a POW. He eventually became a well-respected educator in Frederick County. Nevin, after serving in the Marine Corps, went into banking.

At College Park, Bill enrolled in the Enlisted Reserve Corps. By the beginning of his spring semester in his sophomore year, he was told he was now in the regular Army. After a three-day visit home, Bill took the trolley to Union Station, and then on to Fort Lee, Virginia, where he went through basic training. Afterward, he was sent to Camp Lee for technical training and truck driving school. He was soon promoted to T-5, working in the mailroom. Tiring of this, he filled out forms to either enter Officers’ Candidate School (OCS) or join the paratroopers.

The camp commander, D. John Markey, a good friend of Bill’s father, strongly suggested that a rifle company was not the best place to be and urged him to return to Quartermasters’ School at Camp Lee. Bill took Markey’s advice and eventually was assigned to Camp Campbell with the 4332 Service Company as the 2nd Platoon Leader. The company consisted of four white officers and 212 African American soldiers.

First, they were sent to Fort Devan for two weeks, and then they were placed on a convoy that sailed from Boston in April 1943 to Amsterdam. There was still the danger of German U-boats, and the convoy was guarded by destroyers. After safely arriving in Holland, Bill and another officer had the choice of joining Graves Registration or a supply company for an armored unit. They flipped a coin for it, and Bill ended up in a truck supply company. They rode trucks filled with ammunition for howitzers and tanks. When they got to the Remagan Bridge, they had to wait a few days for the engineers to complete a pontoon bridge to replace the damaged bridge. One day, while staying in a German manor house in the center of town, Bill vividly recalled awaking to the tragic news that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died. Everyone wondered, “What would happen now?”

When in Leipzig, Germany, his company was tasked with taking truckloads of enemy guns, cleaning and repairing them, and then sending them off. The worst experience Bill can remember is when his convoy, carrying ammo, came to a crossroads. The MP there told them to go one direction…the wrong direction! Suddenly, they were confronted with a German howitzer…and quickly turned around. They ended up stuck in a ditch until they pushed the truck out and drove back to safety. Boy, did they give the MP hell for sending them in the wrong direction!

Once, when Bill’s company had crossed near the Remagan Bridge, he was in a foxhole with one of his men when a Messerschmitt flew up the river, shooting at the Americans. They were lucky that time. Usually, ammo convoys had little protection and were prime targets for the Nazis.

Finally, the war in Europe was over, and Lt. Baker was sent to Marseilles, where the troops were staging for the next offense: Japan. He was on a ship for one-and-one-half days, bound for the Pacific when they got a change of orders. They were going home. Bill returned to the shores of the United States, and after a 30-day leave, was eventually discharged in the summer of 1946.

Returning to college, Bill graduated in 1951 with a certificate to teach agriculture. He resumed his friendship with Marguerite “Weetie” Stitely from Woodsboro, who graduated from Hood College in 1947. She became a beloved librarian at Thurmont Elementary School for many years. Bill and Weetie were married in September 1947. They had three children: Bill Jr., Becky, and Katrina.

Bill began a long career teaching agriculture at Emmitsburg and then at Catoctin High School until retiring in 1980. Along the way, he attended an auctioneering school and continued auctioneering even after retiring from teaching. One of his proudest accomplishments was forming the Thurmont & Emmitsburg Community Show, which continues to this day.

No student who took agriculture from “Bulldog” Baker forgot him. He was one of a kind! As a neighbor of the Bakers for 25 years, I treasured their friendship. Sadly, Bill passed away in 2009, and then both Katrina and Weetie followed him in death. William Baker served his country like his father before him, and then spent the rest of his life serving his community. Truly a life well lived.

If you are a Veteran or know a Veteran who is willing to tell his or her story, contact the Frederick County Veterans History Project at priscillarall@gmail.com.

Bill and Weetie Baker